Great Moves Easier for Him on Court

- Share via

No one ever played the game of basketball better than Elgin Gay Baylor. No one. Not Michael Jordan, Larry Bird, no Knick, Celtic, Piston, Bull or Rocket in history.

You want numbers? Only two guys in the history of the game--Wilt Chamberlain and David Thompson--scored more points in a single game than his 71. Only nine in the history of the game scored more regular-season points than his 23,149--and he did it in fewer games, 846, than any of them. Only five players scored more in the playoffs than his 3,623. Only two players in the history of the game--Jordan and Chamberlain--had a higher scoring average than Elgin’s 27.4. Jordan at 32.6 and Wilt 30.1.

Only one player, Jordan, had more points, 63, in a playoff game than Elgin’s 61. Except, Jordan did it in double overtime, Elgin in regulation. Eighty-seven times, Elgin scored 40 or more points. And 17 of those times, he scored 50 or more.

When Baylor was on the court, it looked as if it were raining basketballs. He put up 48 shots one night and made 28 of them. Only Chamberlain and Rick Barry topped that performance. Elgin Baylor with the basketball, like Magic Johnson with the basketball, was enough to strike terror in a defense at the buzzer of a close game.

He was years ahead of his time. Elgin had to invent shots that are standard today. He was as much a con man as a guy with a vegetable peeler on 45th and Broadway. He would show the defender the ball like a guy with a pea under a walnut and then, presto! it would change hands and Baylor would loft it up to the basket while the guy was still watching the other hand. No one ever remembers seeing a shot by Baylor blocked.

He had this nervous tic that seemed to come out only at mid-court when Baylor had the ball. The rest of the time his head was as still as Nicklaus’ over a putt.

He was a regular scoring machine. They didn’t have the three-point basket in those days, so Elgin made up for it by drawing the foul, making the basket and shooting the free throw. He did that better than anyone else. He was one of the strongest men in the game. His teammate, Rod Hundley, always said they ruined a good heavyweight boxing prospect when they gave Baylor a basketball.

Hall of Fame players don’t always make good pedagogues. They frequently have no more idea of how they do what they do than birds. They just get a ball and it happens. Coaches of games are frequently guys who had to scuffle to make the team. General managers often have not even played the game at all. The superstar’s idea of managing frequently is “Go up there and hit a home run--that’s what I’d do here.”

In Elgin’s case, they’d be afraid he’d say: “Go out and throw in 71 points.” To some guy who was hard-pressed to make seven.

Elgin tried coaching for a few years. The New Orleans Jazz weren’t bad. They were awful. Elgin would have had trouble telling the whole team to get 71 points. One year, they had Pete Maravich and not much else.

But Elgin Baylor, since 1986, has been in the throes of a bigger challenge than scoring against a triple team or throwing in 71 points at the old Madison Square Garden.

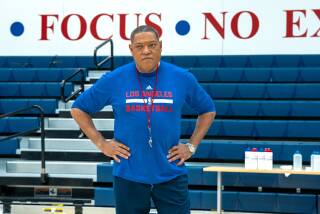

Running the L.A. Clippers is not a job, it’s a gantlet. The Clippers are not a team, they’re an enigma.

Even their antecedence is a little unclear. They were the Buffalo Braves until one day a man named Irving H. Levin traded the Boston Celtics for them.

You heard me. The Celtics for the Braves, even up. But while guys were struggling to get on his mailing list or in a no-limit card game with him, Levin moved the team to San Diego, where, among other things, they traded away the draft rights for what turned out out to be Charles Barkley for a flashy gunner named World B. Free. It was almost as bad as trading the Celtics.

Donald Sterling, the West Coast’s Donald Trump, bought the team and moved it to Los Angeles so he could be nearer his office buildings and movie friends. Eventually, Sterling brought in Elgin Baylor to try to make sense out of a franchise that had managed to cut loose Tom Chambers, Terry Cummings and Ricky Pierce and got a bunch of half-court traffic cops in return. And didn’t learn from it.

The Clippers were like that character in “Li’l Abner” who used to go around with a cloud over his head. No matter what they did, they got rained on.

Elgin found himself going against an old teammate, Jerry West, in his new role. Jerry and Elgin, once one of the most feared 1-2 combinations in the game, were going one on one, West with the Lakers, Elgin with the poor benighted Clippers.

And West had all the moves in this game. The trouble with the Clippers was, they had no identity. A bunch of guys named Smith. The Lakers had Magic, Kareem, Worthy, Cooper. Even their backups were stars. Other teams got Michael Jordan, Charles Barkley, Isiah Thomas. The Clippers countered with one of the most celebrated underachievers in the game--Benoit Benjamin.

When the team won eight games in a row recently, NBA followers were startled. It was so atypical.

But Elgin believes his team is finally in place for a rare playoff run--they have not been in the playoffs since they were the Buffalo Braves, in 1975-76.

“The team has good chemistry,” Baylor explains. “You try to achieve that. You look for talent but you look for other things--a work ethic, character, motivation. Some players are not self-motivated.

“Some are instant stars, but the game has gotten so refined today, you can’t judge a player by his first two to three years. The smart player grows. A Reggie Williams was a six-to-10-point player for us. Now he’s averaging 18 for Denver.

“You look for consistency. When a player has a Michael Jordan night, you know then he can do it. But if he doesn’t give the same effort--or near the same effort--every night, he’ll hurt you.”

Does Baylor, who came into the league as its highest-paid player--$20,000 a year--and who never made more than $150,000 in his best year, resent paying million-dollar salaries to guys who would have played garbage minutes in his day? He shakes his head.

“In ’75 and ‘76, I said that in the next 10 years, players would be making $5 million a year. I don’t resent it, I expected it.”

Does obvious or apparent lack of effort baffle him, frustrate him? Baylor shakes his head.

“There were guys--lots of guys--in my day who were that way. Money spoils some people. It motivates others.”

Adds Baylor: “The game has changed. Nate Archibald was the one who changed it, to my way of thinking. It’s become a fast-break, cheap-basket--what I call the cheap basket--game today. You don’t take 22 seconds to get the shot off anymore, you fast break it.

“But in any day, defense wins. The stars of any day would be still stars today. A Bill Russell would still take the ball away from you.”

The trick is to find the Bill Russell. Baylor simply hopes he can head-fake the NBA from a desk chair as effectively as he did from center court all those years.

More to Read

Go beyond the scoreboard

Get the latest on L.A.'s teams in the daily Sports Report newsletter.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.