A Doctor Hangs Up One of His Most Powerful Therapeutic Healing Tools

- Share via

The Times has chosen in an article (Dec. 29, 1991) whose bias is prematurely revealed by the headline “Betrayal on the Couch” to suggest that sexual exploitation by psychotherapists is so pervasive as to require support groups and a major “expose” in a responsible metropolitan newspaper. Shades of Geraldo or Oprah.

In claiming that as many as 10% of therapists have sexual relationships with their patients, The Times fails to point out that surveys by the concerned professional organizations involved have determined that “sexual relationships” have not necessarily meant sexual intercourse. The term has been broadened to include hugging, patting or even brushing a cheek--gestures that most of us can recognize may easily be misinterpreted, especially in a susceptible clientele who require a therapist’s services. And a fact apparently recognized by the court, in acquitting the physician pilloried by your reporter for his alleged “embrace” of a depressed patient. If genderless gestures of support are to be interpreted as “betrayal,” who among us can be innocent?

We have powerful medicines and effective surgical procedures, but doctors realize that reassurance and hope inspired by contact with a caring physician is still one of the mainstays of successful therapy. It is a feeling of compassion that separates the physician from a computer. If it were otherwise, most treatment could probably be relegated to a machine. A big part of a successful doctor-patient relationship and an enormous part of successful healing depends on the primordial comfort we achieve by the laying on of hands, by touching the patient in an empathetic, clinical fashion.

The infant entering the world is first soothed by the touch of the cradling mother or father. The handshake from a boss after a successful employee effort is acceptable body language without which we are lesser human beings. The physician may have to do more; certainly he should not be forced to do less.

Although I’m not a psychiatrist, many patients I see are frightened, agitated and troubled. When I started to practice over 25 years ago, it was a part of my customary clinical behavior to end certain interviews and examinations by putting my arm around the patient, male or female, and assure him or her that I thought everything would be all right. Usually my nurse or receptionist was present, but since there was never any secondary agenda except my inherent need as a physician to comfort, I did not care who was watching: my nurse or the patient’s parent or a spouse.

Sometimes reassurance was simply verbal. Often it involved a hand on the shoulder or a hug. But the misinterpretation of such well-meaning gestures by emotionally disturbed patients is not news to practicing physicians. We have learned long before the unfortunate article in The Times that although a pat on the back on the football field or a bear hug on the baseball diamond is acceptable, in the physician’s office it is a risky treatment.

There is no question in my mind that some physicians do injure patients. Some make wrong diagnoses, some prescribe incorrect treatments and some do poor surgery. And since mere mortals can get a medical degree and mere mortals can err, some become disabled by drugs and/or alcohol and some indulge in antisocial behavior. However, in over a quarter of a century of practice, I can recall only one report to me of an episode of sexual exploitation of a female patient by her physician and that was a touch by an orthopedic surgeon that may have been misinterpreted.

But as a result of manipulative horror stories like those given prominence in The Times that must involve at most only a tiny minority of patients, I can no longer yield to my natural instinct to comfort by the primitive reassurance of a fatherly hug. I have to think twice before patting a patient on the back. And I usually limit physical touch to the orthodox procedures of a physical examination or a handshake.

Because I have to be concerned that a few disturbed persons may misinterpret my humanity for lust and that such individuals have the potential to alter my life, I have learned that I must abandon one of my most powerful therapeutic tools for psychological healing. And that is, indeed, too bad.

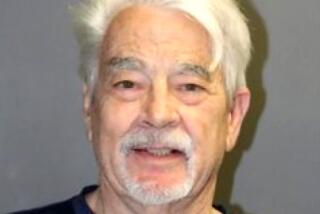

ARTHUR D. SILK, MD, Garden Grove