How U.S. Can Slow Rising Health Care Costs--and Cover the Uninsured

- Share via

The end of the Cold War raises hopes that the considerable resources that the United States has devoted to deterring and countering the threat of Soviet aggression can be put to more productive uses.

Almost everyone in Washington has a plan for the “peace dividend.” Some would use it to cut taxes, others to increase domestic spending, still others to reduce the federal budget deficit. The pot of gold has many claimants.

In fact, however, reducing the rate of growth of the nation’s health costs could produce a dividend far larger than the peace dividend. The defense budget is now less than 5% of the gross domestic product and on a downward track.

The President’s increasingly bold proposals to reduce both strategic and conventional forces would bring defense spending down by about 1.5% of GDP by 1997. More aggressive force reduction might bring spending down somewhat faster. However, a maximum estimate of the potential peace dividend is that by the end of the decade we will be spending 2% less GDP on military forces than we are now.

By contrast, the nation as a whole is now spending about 13% of GDP on health care, and the proportion is rising rapidly. By 2000, we will probably be spending at least 17% of GDP for health care and looking at 20% in another decade. Clearly there is a greater potential for redeploying resources to other uses by cutting the rate of growth of health care costs than by accelerating the decline in the defense budget.

Is it realistic to think that the United States could reduce the growth of health costs without reducing the quality of care, resorting to socialized medicine or aggressively rationing care?

The experience in several other industrial countries offers hope that we might. France, Germany and Japan, for instance, spend about two-thirds as much of their GDP on health care as we do, yet their standards of care are sophisticated and their population is as healthy and long-lived as ours.

None of these countries has socialized medicine. Their doctors are mostly in private practice and paid on a fee-for-service basis. They have both public and private hospitals, and patients choose their own providers. Most people obtain health insurance through their employers, but coverage is universal, not limited to those with jobs.

In contrast to the United States, health insurance in these countries is standardized--everyone has the same plan--which greatly reduces administrative costs. Moreover, doctors, hospitals and other providers are all reimbursed at the same rates for particular services.

An overall target for health spending is established. Then a formal bargaining process sets reimbursement rates that are designed to keep spending within the national target.

The French, German and Japanese health insurance systems seem less different from ours than the Canadian system. Canada has public health insurance for everyone. Neither employers nor insurance carriers are involved.

Provincial governments pay all the health claims, negotiate reimbursement rates for doctors, hospitals and other providers, and control the acquisition of high-tech medical equipment to make sure that it is efficiently used.

Despite universal coverage, Canada’s medical spending is a significantly lower fraction of GDP than ours and rising less rapidly. The administrative costs of their system are a fraction of ours. There are more doctors relative to the population than in the United States, and doctors’ incomes are somewhat lower.

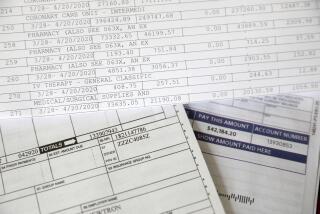

In the United States, health costs are skyrocketing out of control, and increasing numbers of people are without insurance. Both problems need to be solved together.

If a choice is necessary, the cost control problem should be given priority. Without aggressive cost controls, subsidizing health insurance more generously through the tax system, as the President has proposed, will only escalate costs more rapidly.

If the United States were to move to a system of standardized insurance and controlled reimbursement rates, it would not be unrealistic to reduce health care spending by 2% of GDP below the level expected at the end of the decade. This health cost dividend could be used to provide health insurance for those who do not have it.

The health cost dividend, like the peace dividend, would cause some dislocation in the economy. There would be winners as well as losers.

Doctors’ incomes would rise more slowly. Part of the army that works in marketing, administering and interpreting competing health insurance plans would be looking for other employment. Doctors and hospitals would lay off some clerical personnel.

However, the benefits of a simpler, less costly health payment system, both to business and to individuals, would be substantial. Moreover, unlike the diminishing peace dividend, the health cost dividend would continue to grow in the future.

More to Read

Get the L.A. Times Politics newsletter

Deeply reported insights into legislation, politics and policy from Sacramento, Washington and beyond. In your inbox twice per week.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.