Iraq Farm Projects Called Peril to Antiquity Sites

- Share via

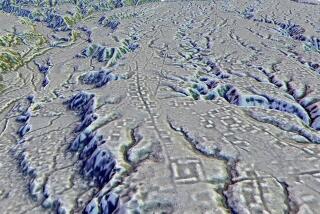

BOSTON — The Iraqi government is so desperate to feed its people it has started big farming projects that could inflict more damage on valuable archeological sites than bombing in the Gulf War, experts say.

“I kind of understand why they would want to go out and make the desert bloom,” said Paul Zimansky, professor of archeology at Boston University. “Given the strains in Iraqi society, nobody has time to worry much about antiquities.”

Zimansky returned in January from Iraq, where he saw large-scale plowing and newly dug irrigation ditches on land known to harbor archeological sites.

He and his wife, Elizabeth Stone, a professor of anthropology at the State University of New York at Stony Brook, tried to visit the site of a Mesopotamian city they were excavating before the war.

But an area of cultivated land about 8 square miles blocked the way to the 4,000-year-old city of Mashkan-shapir. They don’t know if the ancient site, about 85 miles southeast of Baghdad, is intact.

“If a site like that has been plowed up, we have lost all that information on how an old Babylonian city is organized,” Zimansky said. “What we don’t know, we can’t put a price tag on.”

Mesopotamia, in what is now the heart of modern Iraq, was one of the world’s first civilizations.

Before the war, Iraq’s agency overseeing antiquities had so much clout it could forbid military maneuvers near an archeological site, Stone said. Now the department has no working telephone and staff workers have to borrow cars.

McGuire Gibson, professor of Mesopotamian archeology at the University of Chicago, said Iraq was supplying water and other materials to private farmers in the desert.

“They’re basically encouraging anyone who wants to farm to take the land and go out and do it,” Gibson said. “This is land that has been abandoned for centuries.”

Experts disagree over how much damage the heavy bombing of Iraq in the Gulf War caused to archeological sites.

“We have no idea what is around factories and things that were bombed,” Gibson said. “There are sites all over the place.”

Zimansky said damage was relatively light, partly because the allied forces targeted military sites with precision. Also, many ancient sites in Iraq are buried and spread out over large areas.

“People have the wrong vision, they see columns standing up, they see the Parthenon,” said Zimansky. “That’s not what a Mesopotamian site looks like.

“It looks like a vast sand bar. A bomb here and a bomb there just puts a hole in one place.”

Well-known ancient sites such as the ziggurat at Ur escaped major damage, Zimansky said.

He said he saw a few bomb craters near the ziggurat, a terraced pyramid first excavated in the 1930s. Holes in the structure’s thick walls may have been made by bullets when U.S. planes strafed the area near an Iraqi air base, Zimansky said.

Iraq has as many as half a million archeological sites, including 100 or 200 ancient cities.

“There’s so much to dig in Iraq,” said Jerrold Cooper, a professor of Assyriology at Johns Hopkins University. “In the broader scheme of things, I personally wouldn’t worry about it.”

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.