PERSPECTIVE ON EDUCATION : Bottom Line Is King in Schools for Profit : Money-making institutions promote the values that attract the most paying students. They fail a public trust.

- Share via

It’s no trick to run a profitable private school: Just steal the best students.

Private schools don’t have to educate everybody, as the public schools do, so they pick and choose. Students who are profit-intensive (bright, passive consumers with disposable income) are prized. Students who are cost-intensive (slow learners, the disadvantaged, victims of discrimination) are not.

Even private schools with “open” admissions take the cream off the top, because the students they don’t want are unlikely to be able to pay thousands of dollars in tuition.

That’s why, no matter what they say for public consumption, the alliance of Yale University President Benno C. Schmidt Jr. and Tennessee businessman Christopher Whittle is a declaration of war against public education. And at this time, the resources to win that war appear to be on their side: the lure of profit, the backing of corporations, the mesmerizing promise of “high-tech” teaching methods and support from the elites who benefit.

Schmidt announced last week that he would join Whittle in a plan to open 1,000 “high-tech, private, for-profit schools” by the year 2010. What a tragedy that businessmen like Whittle and educators like Schmidt want to benefit themselves at the expense of public institutions.

If Schmidt and Whittle have their way, public schools will exist only as dumping grounds for cost-intensive students. Since these are the same people whose parents are least likely to be influential (or even vote), political support for public education spending will erode. Lower budgets will again reduce quality, and so on, in an endless downward spiral. Eventually, the same people who run private prisons will find ways to make money from a private “school,” warehousing cost-intensive students. Public education will come to a dirty, ignominious end.

Whittle has been clear about his intentions: He regards students as consumers to be marketed to the highest bidder. Consider “Channel One,” the television program that Whittle provides to some school systems. Between the news updates that are its ostensible purpose, Whittle mixes in kid-targeted advertisements for food and clothing. He’s got a captive audience of students; for an advertising man, it’s like shooting fish in a barrel.

The $60 million to design Whittle’s schools is coming from Time Warner, Philips Electronics N.V., Associated Newspapers of Britain and a group of personal investors led by Whittle himself. It is unlikely that they are risking their money out of public spirit.

Whittle expects much of the $2.3 billion to build the system to come from corporations supplying school products, such as computers. He may sell stakes to companies like McDonald’s, which could recoup its investment by selling hamburgers to the captive school-lunch audience.

The values at the core of the Schmidt/Whittle plan ought to shock us. They say that it’s OK to pursue profit at the expense of educational quality. They say that it’s OK to benefit the few to the detriment of the many.

The whole point of public education is for children to be taught, as nearly as possible, our values--the values we share as a society. That’s why schools are, and should be, in the hands of the public, which can determine school policies through frequent free elections--not in the hands of profit-making corporations, which will determine policy on one basis only: the bottom line. The values they communicate will be whatever attracts the most profitable students.

How have we reached this point? If public schools have failed to express our common values, it is our fault: It is because all of us--parent, child and interested citizen--have failed to participate in determining those values. We have failed to understand or use this tremendous gift from earlier generations of Americans; now Schmidt and Whittle will try to take it away from us.

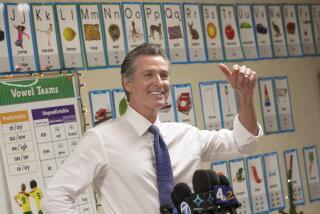

Look carefully at the enormously privileged, well-educated, happy-looking face of Benno Schmidt; it is, tricked up in softer modern garb, the face of Wackford Squeers, the schoolmaster of Dickens’ “Nicholas Nickleby,” a man who caned his students and slashed their rations so he could squeeze a little more profit out of his private “school.” If he were here, Squeers would recognize the Schmidt/Whittle plan for what it is--and clap his greedy hands.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.