Heirloom Is History : Rare Copy of Declaration of Independence Will Hang in Nixon Library

- Share via

YORBA LINDA — Wilbur Wright had often looked at the creased and ragged document hanging on his office wall with a suspicious eye.

As a child, the 71-year-old Wright recalls, he saw the reproduction of this country’s Declaration of Independence hanging at his grandfather’s house in Pomona as early as the 1920s. He also knew it had gathered dust in his father’s closet for 16 years.

“He never said anything about it,” Wright said of his father. “As I reflect upon it now, he was a pretty stern gentleman. But I knew it was something because it had traveled--from Maryland to Missouri, to Omaha, to Pomona--in the family for 150 years.”

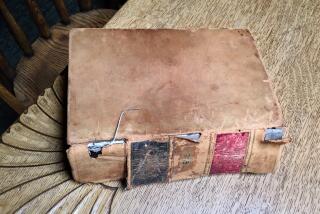

That’s why he asked a local historian in April to take a look at the calfskin print. Carefully examined by manuscript expert William Coleman of Laguna Beach, who has devoted nearly 10 years to locating and verifying similar works by an early American engraver, it was determined to be one of only 32 surviving copies commissioned in 1820 by then-Secretary of State John Quincy Adams.

“It has lain dormant for a bunch of years,” said Wright, a 19-year resident of Yorba Linda. “Nobody in the family seemed to have much interest in it.”

So the family decided to donate the poster-size copy to the Richard Nixon Library in Yorba Linda, where it will be on permanent display beginning Thursday.

Wright’s grandfather, who moved the family to California about the turn of the century, commissioned a family history in an attempt to determine who had acquired the document and when. According to family lore, “one day, when the family was living in Maryland, a black woman knocked on the door desiring to sell it,” Wright said. “They bought it and we have had it in the family since.” He thinks that happened in the 1840s.

But the details and exact date remain unknown because the family history commissioned by his grandfather was lost in 1975 when his parents moved into a retirement home, Wright said.

The document has been identified as an engraving by William J. Stone, who labored for three years duplicating the parchment original. Adams, who went on to become President, feared that the original Declaration of Independence was showing signs of deterioration where it was displayed in the government Patent Office.

In 1823, the 201 engravings Stone produced from a copper plate were distributed among high officials in the White House, the U.S. Congress, various government agencies, and each of the states and territories of the union. Stone kept a copy for himself, and those that were left were sent to colleges.

The Wrights’ copy originally had been given to a Joshua Prideaux about 1823. Officials at the Library of Congress in Washington have not yet learned any details regarding Prideaux.

In the intervening years, most of the copies have disappeared. Today, 19 copies are held in institutions and government offices and 13 are held in private collections--including Wright’s copy. In 1991, one of the copies was auctioned off for $85,000.

“It is an exciting find,” said Don Wilson of the National Archives in Washington, where the original document is now housed. “There are only 32 known to exist. Many of them have been thrown away or lost by families who didn’t know what they had.”

Wright said he kept the copy on his office wall in a glass-fronted frame for 16 years. His daughter, Susie Spreen of Laguna Niguel, said that when Wright underwent cancer surgery five years ago, he was prompted to look into the origins of the document once and for all.

The document will be unveiled at the Nixon Library in a ceremony at 10:30 a.m. Thursday. It will be displayed in a glass case in the center of the Domestic Affairs Wing at the library, which houses documents detailing the former President’s achievements.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.