San Marcos Resident Wins Medal for Inventions : Citation: White House recognized W. Lincoln Hawkins, 81-year-old retiree of Bell Laboratories, for strides he made in technology. He has also worked to further the scientific education of blacks.

- Share via

During a brief return to his native Washington last month, San Marcos retiree W. Lincoln Hawkins made a stop at 1600 Pennsylvania Ave. to receive a National Medal of Technology from President Bush.

Hawkins, 81, received the award for crucial discoveries he made during a 35-year career at AT&T; Bell Laboratories, the telecommunications research lab and think tank in Murray Hills, N.J. Hawkins’ patented discoveries in telephone cable insulation enabled Bell to cheaply string telephone lines across the nation.

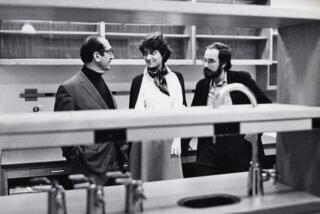

A Ph.D in chemistry, Hawkins in 1941 became the first black scientist hired at Bell Labs, the celebrated spawning ground of research and invention. Since his retirement, Hawkins has been active in programs designed to encourage inner-city youths to pursue careers in science, efforts that were also lauded at the White House ceremony on June 22.

Trained as a materials engineer, Hawkins and other Bell Labs scientists faced a dilemma as World War II came to a close and as the Bell System was gearing up for a huge surge in demand for telephone service.

Up to then, telephone cables were insulated with lead, which was both too heavy and expensive for widespread installation. Bell knew that, to make the telephone system a truly universal utility, they would have to find a lighter and cheaper substitute.

Hawkins and Bell Labs associate Vincent Lanza focused on a polymer that was developed by British scientists for possible use as synthetic rubber. Although lightweight and cheap, the polymer broke down rapidly in severe weather conditions, leaving the cables susceptible to the short circuiting that results from poor insulation.

“The British thought it was not going to be commercially practical because it lost strength. They ruled it out, but we couldn’t afford to rule it out,” said Hawkins, who bought a retirement home in San Marcos in 1990 to be closer to his grandchildren. “It had everything we needed except stability. We simply had to have it.”

Hawkins’ and Lanza’s breakthrough was their invention of an anti-oxident additive that inhibited the breakdown or oxidation of the polymer outdoors. The invention, which gave telephone cables a 25-year life span, saved Bell an estimated $1.8 billion in insulation costs over the first 25 years of its use, according to a Bell study.

‘The value of their discovery was that it made inexpensive plastic the material you could use for telephone cable insulation, replacing more expensive and more unwieldy lead,” said Robert Laudise, director of new materials and processing research at AT&T; Bell Laboratories in Murray Hills.

The Hawkins-Lanza invention “was the main contributor in making universal telephone service possible,” Laudise said Monday.

The patent on the invention was assigned to Hawkins and Lanza, but, as is the case in all patents received by Bell Labs scientists, the technology became the property of Western Electric, Bell’s manufacturing arm. Lanza was killed in an airplane crash in Great Britain in the early 1950s.

The patent was one of 18 that Hawkins received during his tenure at Bell Labs. But he said he has no regrets about the fact that he does not “profit personally” in the form of royalties from the technology he helped develop. He found his reward was in the ability to freely follow lines of scientific inquiry and to work among “a stimulating group of people.”

“My stimulation came from other people at Bell Labs. We always talked freely about what we were doing. If the system had said we were getting a fraction of a per cent in royalties from what we were doing, my notebook would have gone home with me every day, and I would have not told anything to anyone. Who knows if we would have been able to accomplish anything under those conditions.”

Growing up in Washington, Hawkins said, he was always interested in “gadgets of one sort or another” and spent hours studying the exhibits in the Smithsonian Institution as an elementary school student.

Hawkins began to consider science as a vocation when Mr. Weatherless, one of his high school science teachers, revealed to the class that the new Reo car he drove to school was a benefit of his having invented a component used in the automobile’s starters.

“That was good exposure for a student of my impressionable age of what patents could mean to you,” Hawkins said. “He was a good role model. He showed me that it was exciting to get a patent, that you could get a car out of it.”

Hawkins went on to get degrees at Howard University, Rensselaer Polytechnic Institute and McGill University in Montreal, and a teaching post at Columbia University before being hired by Bell Labs in 1941, the first black to join the select group of scientists.

Was his status as pioneer a burden?

“I was much more comfortable than some of the people I was working with,” Hawkins said. “You have to remember that I had just come from living for three years in Canada, a completely integrated society. So I didn’t think anything of it.”

Just as Mr. Weatherless in his shiny new auto served as a role model for Hawkins, so has Hawkins endeavored throughout his career to be a model for youth.

Laudise said Hawkins helped found Bell Labs’ Summer Research Program by which promising underprivileged high school students are given summer jobs at Bell Labs. He also helped set up a fellowship program at Bell Labs that provides financial and “mentoring” assistance for 200 black graduate college students each year.

Hawkins said he is “still involved with students” through an industrial-based outreach program called National Action Council for Minorities in Engineering, whose board Hawkins formerly chaired.

Attracting the younger generation to scientific careers, Hawkins said, must become a high priority in a nation that is fast losing its lead in pure scientific research.

Hawkins was one of seven recipients of the technology medal, which was first presented in 1985.