MEDICINE / HEPATITIS : Vaccine 100% Effective in First U.S. Test

- Share via

In its first American study, a new vaccine against hepatitis A has proved to be 100% effective in protecting children against the infectious liver disease.

Successfully testing the vaccine is a “significant milestone” that marks the first improvement in preventing hepatitis A in 50 years, said Dr. William H. Bancroft of the U. S. Army Medical Research and Development Command in Frederick, Md.

Although outbreaks of the disease can be controlled by sanitation measures, many groups in the United States are at high risk of developing hepatitis A, including travelers, military personnel, American Indians, children in day-care centers, institutionalized persons and those who practice anal sex.

About 23,000 people in the United States developed hepatitis A last year, and its annual cost to the U.S. economy is estimated at more than $200 million.

Researchers at the Kiryas Joel Institute of Medicine in Monroe, N.Y., tested the new vaccine, made at the Merck Research Laboratories by killing the hepatitis A virus, in children in a Monroe Hasidic Jewish community that is subject to regular outbreaks.

None of the 519 children who received the vaccine developed hepatitis A, the researchers report today in the New England Journal of Medicine, while 34 of the 518 children who received a placebo did develop it. As a side effect of the vaccination program, the incidence of the disease in the community was sharply reduced. Based on this success, Merck hopes to have approval from the U.S. Food and Drug Administration to begin marketing the vaccine in 1994.

“The hepatitis A vaccine appears to be highly safe and very effective,” said Dr. Mirian Alter of the U.S. Centers for Disease Control in Atlanta, “but we have not developed a strategy for its use, so we can’t say who we will recommend it for. No doubt we will recommend it initially for people who travel frequently to countries where hepatitis A occurs at a high rate,” such as Mexico.

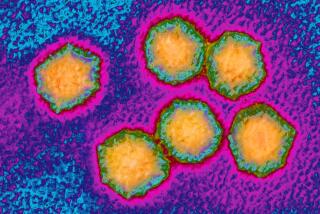

Hepatitis A, once known commonly as infectious hepatitis, is one of five variants of hepatitis now known.

All forms of hepatitis are characterized by inflammation of the liver, usually producing swelling and tenderness. Other symptoms, which can persist for weeks, include fatigue, mild fever, muscle or joint aches, nausea, vomiting, loss of appetite, vague abdominal pain and sometimes diarrhea. About one in 1,000 cases of hepatitis A is fatal.

The hepatitis A virus is shed in feces; the most common sources of infection are contaminated food and water. But it is also frequently spread by eating raw shellfish or by exposure to infected individuals in families, institutions and day-care centers.

Safety trials conducted on 1,600 adults and children since 1987 and have shown that the vaccine stimulates production of antibodies to the hepatitis A virus and produces no ill effects. But to test its effectiveness, Merck needed a population that had a recurrent risk of infection.

That population proved to be the Hasidic Jewish community in Monroe. The community is characterized by rapid growth, large families and enrollment in schools before the age of 3. Outbreaks of hepatitis A originate in the schools in the summer and winter, and the disease is then frequently transmitted to the parents.

Dr. Alan Werzberger, a pediatrician, and his colleagues at the Kiryas Joel Institute identified 1,037 children, ages 2 to 16, who showed no evidence of previous exposure to the virus. Half received the vaccine and half received a sham injection or placebo, beginning in June, 1991.

In the first 21 days after vaccination, seven cases of hepatitis A developed in the vaccine group and three in the placebo group. Because of the long incubation period of the disease, all of these patients were clearly infected before enrolling in the trials.

After the 21st day, no more vaccinated patients developed the disease, while 34 in the placebo group did.

By November, the results had become so conclusive that the team ended the trial and vaccinated the children who had received placebos. Because half the children in the community were enrolled in the study and another 20% were already immune to the disease, the vaccination program caused an abrupt drop in the number of infections.

“Last November alone, we had 30 cases in the community,” Werzberger said in a telephone interview. “Since then, we have had no more than three total.”