Safer Test for Birth Defects Reported : Medicine: Researchers succeed in isolating and examining fetal cells from mothers’ blood.

- Share via

In the first large-scale application of a new, non-invasive prenatal test for birth defects, Tennessee physicians have used fetal cells from the mothers’ bloodstreams to identify seven fetuses with chromosomal abnormalities among 69 pregnant women studied.

The chromosomal abnormalities were of the types that produce Down’s syndrome and other severely debilitating birth defects.

Researchers have high hopes for the new test, which uses sophisticated techniques to isolate the extremely rare fetal cells from the mother’s blood. “It opens up prenatal diagnosis to the whole population because there is no risk to the fetus,” said Dr. Sherman Elias of the University of Tennessee, primary author of the paper.

The more conventional prenatal tests--amniocentesis and chorionic villus sampling--both pose a small but significant risk to the fetus because a biopsy needle must be inserted into the womb.

For younger women, the risk from these procedures is greater than the risk of having a Down’s baby, so neither test is normally given to pregnant women under age 35. But 85% of Down’s babies are born to women under age 35.

The new technique, described Wednesday at a meeting of the American Society of Human Genetics in San Francisco, is so promising that the National Institutes of Health is organizing a nationwide trial in which the new method will be used on 3,000 pregnant women.

“This is not ready for use at your local doctor’s office yet, but we are ready to test it in much larger numbers of people,” said Dr. Diana W. Bianchi, a medical geneticist at Boston Children’s Hospital.

In a separate study reported at the San Francisco meeting, Dr. Wolfgang Holzgreve of the University of Munster in Germany reported that he had used the new technology to detect an abnormality called trisomy 18 in four pregnant women. Trisomy 18 produces low birth weight, congenital heart disease, severe retardation and a limited life span.

The new technology makes use of the fact that a very small number of fetal cells, particularly red and white blood cells, leak into the mother’s blood during the first and second trimesters of pregnancy. Such cells account for about one in every million cells in the mother’s blood. A typical blood sample used for genetic testing, about four teaspoons worth, contains about 200 fetal cells.

The presence of these fetal cells in the mother’s blood has been recognized for more than 100 years, but it has only been within the past five that researchers have devised ways to separate the fetal cells from the mother’s. The key is to identify proteins that are present on the surface of the fetal cells but not on the mother’s cells.

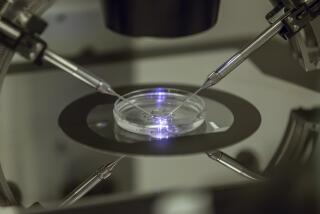

Molecular biologist Kathy Klinger and her colleagues at Genzyme Corp. in Cambridge, Mass., have developed specialized antibodies that recognize and bind to these fetal proteins. The antibodies are attached to a fluorescent dye that allows the cells to be identified by a high-speed, computerized cell sorter. This process, called fluorescent in situ hybridization, or FISH, takes about three hours.

Once separated from the mother’s blood, the fetal cells are then examined to determine whether they have the correct number of chromosomes, which contain the genetic blueprint for humans. This process takes another day or two.

So far, the researchers have studied primarily patients in which the fetal cells have an extra chromosome.

Researchers are not yet able to analyze for other genetic defects, however, because the fetal cells are still contaminated with the mother’s cells. If the mother is the carrier of a genetic disease, Bianchi said, the physician would not yet be able to determine if an observed genetic defect was in the cells of the mother or the fetus. The researchers contend, however, that the technique will be advanced enough so they will be able to completely remove all of the mother’s cells within another year or two.

In the forthcoming nationwide trial of the new technique, the investigators will study blood samples from high-risk women who are also undergoing conventional genetic screening so that the relative effectiveness of the two approaches can be compared.

“If it works in high-risk women, hopefully it will work in other women as well,” Bianchi said. And, added Bianchi, the FISH technique should not only be safer, but also faster and less expensive. Conventional genetic testing costs about $1,000 and may take two to six weeks. FISH screening should cost only a few hundred dollars and results could be available in three to four days.