Noriega Appeals for Lenient Treatment : Court: Attorneys urge a federal judge to bar U.S. from putting him in a maximum-security prison. They insist the former foreign leader is a POW.

- Share via

MIAMI — Attorneys for Manuel A. Noriega asked a federal judge Friday to bar the U.S. government from sending the former Panamanian ruler to a maximum-security penitentiary to serve his 40-year sentence for drug smuggling and racketeering.

Insisting that Noriega remained a prisoner of war even after his April conviction, defense attorney Jon May said the government had already violated the Geneva Convention--which dictates treatment of prisoners of war--by confining him for several weeks in a medium-security prison in Talladega, Ala., after Hurricane Andrew damaged the prison in South Dade County where he has been held for almost three years.

May asked U.S. District Judge William M. Hoeveler to order the Bureau of Prisons to confine Noriega at a minimum-security camp on a military base.

Hoeveler said he did not normally tell the Bureau of Prisons where to house prisoners, and wondered: “Where is my authority to say anything at all?”

May contended that “the Geneva Convention unequivocally prohibits this court from sending Gen. Noriega to a federal penitentiary.” He said that in Talladega, Noriega had been held “in solitary, 23-hour lockdown, in a steel cell, and only one guard could speak Spanish.”

“This is such a strange case,” said Hoeveler, who presided over Noriega’s seven-month trial. “He may be the only prisoner of war the United States has, as far as I know. You’re suggesting we put him in something like Spandau, an institution where he is clearly by himself.” (For 20 years, West Berlin’s century-old Spandau Prison held only one man, Rudolph Hess, who had been a deputy of Adolf Hitler and who was convicted at Nuremberg in 1946. He was sentenced to life in prison and died in Spandau in 1987.)

Assistant U.S. Atty. Michael P. Sullivan said the defense motion to bar the government from locking Noriega in a maximum-security prison was premature, since the Bureau of Prisons had not yet decided where to confine him. But he indicated that prosecutors would recommend sending Noriega to this country’s toughest federal penitentiary, in Marion, Ill.

In arguing that confinement at Marion would not violate Noriega’s rights under the Geneva Convention, Sullivan said he had been there several times to interview convicted Colombian drug lord Carlos Lehder, and that prisoners were afforded outdoor recreation time, albeit in “cages they walk back and forth in.”

Sullivan added that the Marion prison also contained a large gymnasium where “I saw a Mafia don shooting baskets.”

Sullivan said the government has decided to treat Noriega as a POW without officially classifying him as one. He said that means wherever Noriega is incarcerated, he would be afforded protections guaranteed by the Geneva Convention, such as monthly Red Cross packages, food, medical care, exercise and freedom of religion. Even if Noriega is accorded POW status, prosecutors said, the Geneva Convention does not prohibit his being moved to a civilian prison after being convicted of a civilian crime.

Hoeveler rendered no final decision on the motion. But he did express an opinion. “If I had it in my power,” he said, “which I may not, I certainly would recommend that he be detained in a facility other than a penitentiary.” He said he would rule within a week.

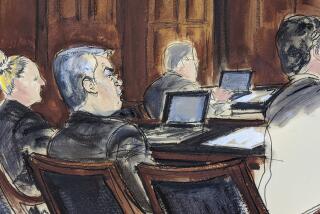

Noriega, wearing his customary khaki uniform, listened to a translation of the hourlong hearing through headphones and on occasion thumbed through a copy of the Geneva Convention, pointing out passages to his attorneys. He did not address the court.

Noriega, seized during the December, 1989, U.S. invasion of Panama, was charged with having turned his country into a way-station for Colombian drug smugglers in exchange for huge payoffs. He was convicted on eight of 10 counts, and sentenced in July.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.