Song of a Dying Culture : Exhibit: ‘Music of the Maya’ curator says traditions, rituals can’t last past the decade because of pressures from religious to political.

- Share via

FULLERTON — The millions of Mayas that make their home today in the highlands of Guatemala constitute perhaps the most distinct and vibrant culture in Latin America today. Many of the Mayas continue to speak their own language, make and wear traditional clothing and take part in ceremonies and rituals that have roots in the days before the Spanish arrived.

That culture is rapidly coming to an end, however, under an array of pressures from religious to political. So says Samuel Franco, founder of Casa K’ojom, a museum in Antigua, Guatemala, dedicated to recording and preserving Mayan musical traditions.

“All the things that make this culture unique, or different, are what we are losing, unfortunately,” Franco explained in an interview in Fullerton. “I don’t think it will last more than this decade. . . . It’s unavoidable. There’s nothing you can do.”

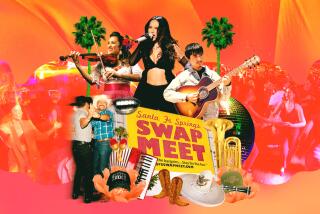

Franco was in town recently for the opening of “Music of the Maya,” the current exhibit at the Fullerton Museum Center. He curated the show with the help of the Museum of Man in San Diego, where it originated. The exhibit traces the history of Mayan music and illustrates its all-important position in ceremony and ritual.

Franco, a sound recording engineer, became aware of Mayan ritual music as he traveled through Guatemala working on films and documentaries. “I realized that a lot of these (traditional) ceremonies were still going on, and no one was recording them,” Franco said. Also, he began to realize “how fast these traditions were changing or disappearing.”

From 1984 to 1987, Franco traveled to Mayan communities in the highlands of Guatemala (and part of southern Mexico), following a calendar of festivals and making sound recordings of ceremonial music as it has been performed for centuries. “I thought it was like a duty to do it, for my community,” said Franco, who is Guatemalan but not Mayan. “And, it is fun.”

In 1987, he said, “I realized I had a lot of recordings,” so he opened up his own museum. As a site he chose Antigua, Guatemala’s old colonial capital, relatively close both to Guatemala City and its universities (about an hour away) and to the heart of highland Mayan culture. The museum has permanent displays of traditional instruments and other items, but the heart of the museum is its archive of sound and video recordings (Franco started using video about two years ago).

Mayan ritual music usually accompanies dance and can take many forms, depending on the occasion. Instruments include flutes and drums like those that were used in pre-Columbian times, plus others that were introduced by the Spanish: brass and stringed instruments, a double-reed flute brought to Spain by the Moors, and even the marimba, brought to Guatemala by African slaves.

Franco’s work records a culture that changed only slowly for centuries after the traumatic upheaval of the Spanish conquest, only to undergo a rapid disintegration in the last decade. Ceremonies and traditions that were once inviolable are slipping away, even in some of the more remote towns and villages.

One of the main factors is the massive evangelical invasion that began in earnest in the mid-’70s. Protestantism and evangelism have a stronger hold in Guatemala than elsewhere in Central America. For more than a decade, evangelical faiths have been growing at an estimated 12% a year, and it is estimated that the country’s population is now more than 35% evangelical.

In Santiago Atitlan, a town of about 30,000 people that is commonly viewed as a center for traditional Mayan life, there are now more than 30 evangelical churches, and their Sunday services are broadcast by loudspeakers throughout the normally sleepy village.

The rise has come at the expense of Catholicism, the religion imported by the Spaniards that until recently dominated the country. In imposing the religion, the early priests allowed a degree of latitude that led to a baroque blend of Catholicism and traditional beliefs, giving Mayan religious ceremonies and practices a fascinating twist that would doubtless give a straight Catholic pause.

“They accepted Christianity, but they never lost some of their traditional beliefs,” Franco said. But evangelical faiths have aggressively attacked the practices as paganistic, and converts no longer take part. Some of the musical instruments and other artifacts in Franco’s museum were found in dumps, where they were abandoned by their former users.

“Some of these new religions do not believe in the masks, the dance,” Franco said. “There’s nothing we can do about it. People can choose whatever religion they want. All we can do is document it.”

Other factors are at work as well, including the advent of television, which broadcasts mostly foreign programming. “The cable era has arrived,” Franco said. “We’re losing our identity. We identify with Mexican TV or American TV.”

The cost of putting on the festivals, too, is becoming prohibitive. Renting or making costumes, hiring dancers, paying for fireworks can add up to $30,000 for a one-day festival in a large town. This, in a country where many of the Indians must work on huge coffee plantations for as little as $2 a day.

Also in the last decade, Mayas have been killed indiscriminately by troops and guerrillas, caught in the middle of a war.

Despite all this, traditional ceremonies and practices, with their music and dance, continue in many towns and villages of the highlands. About 20 of the Mayan languages such as Mam and Quiche are still spoken. Colorful weavings, the hallmark of Guatemala, are still worn and sold in the street markets.

But Franco holds little hope that the steady deterioration of the culture will be reversed, and he worries that Guatemala will someday soon look much like every other Latin American country.

“It’s very hard to see these instruments anymore,” he said, showing a tun , or split-log drum. He holds up a traditional Mayan flute, one that is still played in ceremonies. “These are still used, but only by the old men,” he said. “If kids play in school, it’s probably on a Yamaha.”

* “Music of the Maya” continues through Feb. 7 at the Fullerton Museum Center, 301 N. Pomona Ave., Fullerton. Noon to 4 p.m. Wednesdays, Saturdays and Sundays; noon to 9 p.m. Thursdays and Fridays (except Dec. 24 and 25). $1 to $2. (714) 738-6545.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.