His Mother’s Son : FLAUBERT By Henri Troyat ; Translated from the French by Joan Pinkham (Viking: $25; 359 pp.)

- Share via

Several years ago, I appeared on a Canadian radio talk show with two other biographers, one French, one English. The host asked if any of us was aware of biography as having a particular nationalistic cast; i.e., do Americans, for example, write other people’s lives differently from the British or French? Before the other panelists had time even to think about the question, I jumped in and began to answer it.

The reason this particular moment stuck in my mind ever since was that, until I heard the question, it was something I had never, ever, thought about. And yet, suddenly there I was, eagerly talking away, spouting a theory I had no idea I held until I began to speak it.

What I said went something like this:

Americans will research a topic to death, piling up footnotes, amassing huge bibliographies and telling more than anyone might ever want to know about a person, resulting in a book so heavy it’s difficult to hold and daunting to read (I’ve been accused of this a time or two).

The British write a beautiful story, but are excessively cavalier about listing their sources. It’s as if, having told an engrossing tale, they expect you to take their word for its accuracy and truthfulness.

As for the French, well--and here I remember taking a deep breath and thinking for a long moment of dead-air time. The French, I said, write biography as if it were a graduate-school thesis, deciding in advance what they will tell and what they will omit. Then they use that thesis as if they were constructing a tight little box to enclose the life at hand, determined to make it fit no matter what.

I finished what could probably be called my own little thesis of nationalistic biography and waited for an attack. To my utter amazement, none came. Everyone agreed that I had just described how each of us--as well as most of our compatriots--worked.

As I read Henri Troyat’s life of Gustav Flaubert, I could not help thinking about this discussion. Troyat, one of France’s leading biographers, has specialized previously in the lives of Russian writers, among them Dostoevski, Tolstoy and Chekhov. Now he has turned his attention to Flaubert, whose life has inspired countless previous biographies. Troyat follows in the footsteps of so many other distinguished writers, including his fellow countryman Jean-Paul Sartre, the Americans Francis Steegmuller and Herbert Lottman, and Britain’s Julian Barnes.

Some of these, along with very few of the many others who have written about Flaubert, appear in Troyat’s bibliography. They are nowhere to be found in his source notes, which is curious because all have introduced new ways of thinking about Flaubert’s life and interpreting his work. Instead, for his relatively few footnotes Troyat chooses to rely entirely on Flaubert’s correspondence and the memoirs of those who knew him. This is probably why Troyat’s version of the life has such a tired ring of familiarity to it. He imparts no new biographical information and does little more than mention the works (most notably “Madame Bovary”) that have made this 19th-Century writer so endlessly fascinating.

He does have a thesis, however, and in that he is fortunate, because Flaubert’s life, at least as he himself describes it, fits so neatly into Troyat’s box. This is probably why he takes Flaubert’s version of himself, as he told it in his letters and as his friends retold it in their memoirs, to be the gospel truth. Accordingly, Troyat sees Flaubert as being torn throughout his life “between the crude appetites of the flesh and the seraphic aspirations of the soul . . . between the low and the high, between the gutter and the radiant heavens, between the reality and the dream.”

For Troyat, everything must come in twos: Flaubert needed his saintly mother, who spent her entire life catering to his every whim and anticipating his financial needs before he even expressed them, but he also needed prostitutes and mistresses to satisfy his carnal needs, most notably the poet Louise Colet.

At home in Croisset, daily life in his mother’s house was conducted in hushed whispers until Flaubert awakened in mid-morning. Then Mme. Flaubert rushed to his bedside for a long chat, after which he arose at noon, ate a huge lunch and spent the afternoon getting ready to work on his writing far into the night.

When he could not longer resist Colet’s pleas, he would go to Paris for several weeks of hypersexuality, which he frequently ended abruptly to return to the “Poor old Darling,” as he called his mother. Colet, an independent woman who supported herself by her writing and with the help of a series of then-popular writers who were her lovers, sent a torrent of letters to Flaubert to which he replied in copious detail, and which have proven invaluable to scholars who study the development of his fiction.

To Troyat, however, Colet, who had twice been awarded a prestigious poetry prize by the Academie Francaise, is a “scheming beauty” whose talent he scornfully dismisses. He admits grudgingly that Flaubert “drew sustenance” from her, but he writes of what many believe to be the most important relationship in Flaubert’s life with a disapprovingly judgmental attitude that is woefully outdated. Nowhere does he even hint that his may be a one-sided telling of the tale because Flaubert burned all her letters to him, but his to her have survived intact. The entire Colet episode is without reference to recent important feminist scholarship on this and on several other crucial matters. This attitude prevails in Troyat’s descriptions of Flaubert’s other friends, men as well as women.

As for the work, it, too, is seldom described and then only in vague terms of dualism, bifurcation and doubling. One of Troyat’s most detailed descriptions of how Flaubert wrote is as “an unbridgeable chasm between what he felt and what he expressed, between the thought and the word, between the fluctuating content of the dream and the text that took fixed shape on the paper.” This doesn’t help a reader who wants to learn something concrete about the composition of the fiction.

But Troyat does plod dutifully through the usually told details of Flaubert’s life: how, as the son of a prominent doctor in Rouen, he was sent to Paris to become a lawyer; how he had an illness that incapacitated him; how he returned to the financial and physical security of the family home, there to spend the rest of his life writing. What vitality this text has is due to Joan Pinkham’s excellent translation. What little explanation we do get comes mostly from her translator’s notes. For example, it is she who provides the information that experts are still uncertain about what Flaubert’s illness was, and the most commonly held opinion is that it was a type of epilepsy.

All of Troyat’s thesis is neatly delineated except for one thing that still puzzles me: I can’t decide if he ultimately regards Flaubert as very much else than “the big spoiled child whom Mme. Flaubert refused to see as a grownup.” Gustav Flaubert was very much more than that, and he deserves a contemporary biography that will allow his life to unfold as he lived it with all its seeming contradictions, rather than in a tit-for-tat uniformity. He also deserves a biographer who will pay much more attention to the writing that makes his life worth reading about in the first place.

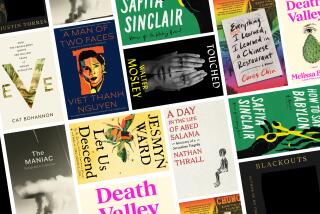

More to Read

Sign up for our Book Club newsletter

Get the latest news, events and more from the Los Angeles Times Book Club, and help us get L.A. reading and talking.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.