ISLAM RISING : East Asia : Region Still a Land Apart : Indonesia, for instance, is world’s largest Muslim nation. But society is more secular, and the faith mingles with Buddhist and Hindu traditions.

- Share via

JAKARTA, Indonesia — On one of Jakarta’s traffic-clogged streets, a visitor recently spied two bumper stickers in English. One said, “I Love Islam,” and the other read, “Be a Good Muslim or Go to Hell.”

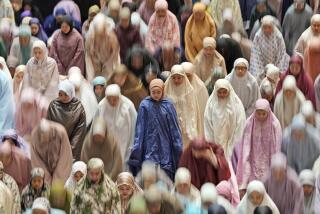

As this informal sampling suggests, an Islamic revival of sorts is under way in Indonesia, which is the world’s largest Muslim country, with an estimated 87% of the nation’s 185 million people calling themselves Muslims.

On the streets of Java, which has traditionally adhered to a moderate blend of Islam, a growing number of young women now refuse to venture out without their jilbabs-- Arab-style head wear that covers all but a small oval of the face.

Attendance at mosques is reported to be surging. Since January, a new newspaper called Republika has been packaging the news with an Islamic flavor.

“People are trying to project themselves as Muslims more,” said Abdulrahim Wahid, head of Indonesia’s largest Islamic organization. “People are trying to find their roots, seeking an anchor against materialism and hedonism brought by development.”

But, for all these changes, Indonesia remains a land apart from countries of the Middle East in the practice of Islam. Even compared to its smaller neighbor to the north, Malaysia, Indonesia in many ways seems like a secular country.

During the recent monthlong fast of Ramadan, for example, restaurants remained open throughout the day, and alcohol flowed freely. In many Middle Eastern countries, restaurants are padlocked until sunset during the fast, and even hotel mini-bars are stripped of their alcoholic drinks.

Part of the difference is cultural. Islam came to Indonesia in the 14th Century, relatively late by Middle Eastern standards. It tended to blend with the country’s Buddhist and Hindu past rather than obliterate it. One intellectual recently quipped that “while Indonesia was Islamicized, Islam was Javanized” by the island’s durable culture.

In Malaysia, in contrast, Islam is closely identified with the Malay character. Islam is the state religion, even though only 53% of the population is Muslim. The leaders of the faith are Malaysia’s nine sultans, hereditary rulers of individual states.

Kelantan, one of Malaysia’s 13 states, is currently ruled by an Islamic political party, which is trying to introduce strict Islamic criminal laws that would bring back the sword and the cat-o’-nine-tails as a form of punishment.

While the rest of Malaysia has not taken such radical steps, Islamic garb there is far more common than here in Indonesia. The government there speaks often about the suffering of Muslims in Somalia and Bosnia-Herzegovina as a way of demonstrating its political commitment to Islam.

Fearing Islam as a political force, Indonesia’s leaders have historically shied away from embracing the faith too closely. Despite the huge majority of Muslims, Islam is not a state religion in Indonesia, which instead endorses a philosophy known as pancasila, or the five pillars. It identifies with a “belief in one God,” a prescription broad enough to encompass a wide variety of religious sects that are openly tolerated in the country.

Virtually since independence, Indonesian governments have tended to regard Islamic politicians as potentially extremist, and their activities have been sharply curtailed, if not banned outright. Preachers have to be certified by the state.

However, in the late 1980s the government of President Suharto made a number of gestures favorable to Islamic groups. Political analysts speculated that Suharto, who was seeking to control restive military leaders, played an “Islamic card” as a counterbalance.

By comparison with Saudi Arabia or Iran, the steps seemed mild: An Islamic bank was created and religious courts were allowed to function, but they may deal only with cases involving marriage and inheritance. A government ban on high school students’ wearing of jilbabs was repealed.

Suharto himself made a popular gesture in 1991 by making his first pilgrimage to the holy city of Mecca. He also authorized his high technology minister, B. J. Habibie, to form a group of Muslim intellectuals into a potent think tank and rallying point on Islamic issues.

Imaduddin Abdulrahim, a graduate of the University of Iowa and one of the leading figures in the intellectuals’ group, had been arrested as a student for his support of a student mosque at the University of Bandung.

“Ten years ago, we were weak and divided,” Imaduddin said. “Suharto was afraid of Islam. He imagined we were like Moammar Kadafi (of Libya). We’re not extremist, we’re just ordinary people.”

The Muslim intellectuals’ group, in fact, now sounds more populist than Islamic to someone accustomed to Middle Eastern radicalism. The hottest issue being discussed by the group at the moment is the gap between wealthy and poor, which has religious overtones because Indonesia’s poor are overwhelmingly Muslim, while the rich are more likely to be Chinese and Christian.

The increase in mosque attendance, for example, is attributed by many to feelings of dislocation brought about by Indonesia’s recent economic boom times. People are drifting from the farms to the cities, leaving behind families and other emotional ties. So they turn to religion to give meaning to their lives.

The intellectuals’ group quietly campaigned against the composition of the government’s last Cabinet because three key economic decision makers were Christian. Although the press portrayed the change as generational rather than religious, the three ministers were dropped when Suharto unveiled a new Cabinet last month.

Although the intellectuals have been content to play an advocacy role so far, many diplomats and political analysts see them as likely to form a potent political movement once Suharto, now 73, passes from the scene.

Already, the group’s loyalists have drafted a new legal code that makes adultery a criminal offense, a move seen as popular among devout Muslims. A provision of the law providing for prosecution for marital rape was widely condemned by the clergy as un-Islamic.

But fundamentalists and strictly orthodox Muslims appear to have remained a tiny minority, with only a few student groups setting up mosques of the doctrinaire Shiite division of Islam, which predominates in Iran, and rejecting the Sunni Islam that is practiced by most Indonesians.

“We Javanese mix our cultures,” said Parni Hadi, editor of Republika, the new Islamic newspaper. “For us, harmony is more important than setting up an Islamic state.”

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.