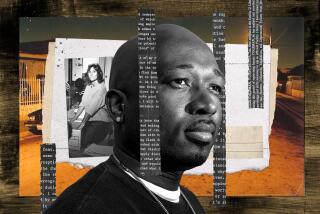

COLUMN ONE : A Death in Carroll County : When Junior Wilson gunned down Travis Lineberry, he cut short a young life and refueled an old debate about a citizen’s right to protect his property--but at what cost?

- Share via

HALE, Mo. — The abandoned house where Junior Wilson shot down Travis Lineberry held little worth stealing, little worth defending to the death.

A mile east of here on a gravel road, the fraying white clapboard had been the Wilson family homestead for more than six decades. But it has stood vacant since Junior’s ailing mother moved out more than two years ago. Hidden by overgrown patches of mulberries and wild grapes, it is one of dozens of weathered ghost houses that rise from the rolling landscape of Carroll County.

When he noticed fresh footprints in the snow during a visit to the house last December, Wilbur Wilson Jr. figured he had a prowler. Another family home had just been cleaned out by burglars, so the 62-year-old farmer decided to stake out the place. He drove down from his farm in nearby Livingston County and, according to police, concealed himself in the shadows of the house’s unheated parlor for four nights with a riot gun and a .357 magnum handgun.

Just after dusk on Dec. 21, the half-deaf farmer heard voices, then saw a figure slip inside. As the intruder approached, Wilson reared up and fired once with his pistol.

The prowler who fell fatally wounded was Lineberry, a neighbor. This was no seasoned burglar, but a burly 16-year-old high school student without a criminal record.

When officials learned that the youth had not brandished a weapon and that the farmer had been lying in wait, they charged Wilson with second-degree murder.

“I was in my house,” Wilson explained to a deputy during an interrogation the day after the shooting. “I figured it was legal that way.”

That it might not be has outraged many landowners in this county of small grain farms and elevator towns just north of the Missouri River. Stubborn believers in the right to defend their property at any cost, many are alarmed by footage of drive-by shootings and home invasions beamed 75 miles into their living rooms in newscasts from Kansas City, Mo.--obscuring the reality that such mayhem almost never occurs in their own back yards.

On the night Wilson and Lineberry met in the dark, those gathering fears butted against an age-old rural tradition--the mischievous teen-age impulse to explore abandoned houses. In a broader sense, their encounter crystallizes an American dilemma that resonates as keenly in the country as it does in urban areas: An armed citizenry can fight crime, but at what price?

Lineberry’s death has divided a community that had long tolerated both its adolescent thrill-seekers and its armed landowners. In Hale, a town of 529 where everyone knows everyone else, it is hard to stay neutral. People have strong bonds to the Wilsons and Lineberrys--families who have farmed in the area for more than a century.

To farmers who can easily see themselves in Wilson’s shoes, young Lineberry could only have been a burglar. Why else would he wait until dark to break into a sealed house?

To the Lineberry family and many area teen-agers, the question is how could a well-armed man fire almost point-blank without yelling a warning, flicking on a light or first firing a shot into the air?

“It’s a shame to see people blacken the reputations of these two people,” says Willis Swearingin, a former county sheriff. “Feelings are real hard on both sides. If only that bullet had missed.”

Wilson, a sunken-cheeked wisp of a man who has been on heart medication while preparing for a trial that starts Monday, could face 10 years’ imprisonment to life if he is convicted on the murder count and two related charges. He has told friends he had no idea whom he faced in the parlor. That night, he was not about to ask.

“He didn’t know who he was dealing with, a kid or a killer,” says Roy Curry, a neighbor and longtime friend. “He could’ve been dead if he waited to find out.”

Wilson’s case has become a cause celebre among gun rights activists that is reminiscent of the recent controversy over a Baton Rouge, La., man’s acquittal for shooting a Japanese student who approached his house for directions. Gun owners around the nation have written Wilson to lend moral support. A defense fund has been set up and the National Rifle Assn. referred him to Kevin Jamison, a Kansas City lawyer who keeps a loaded .44 in his office “just in case.”

Jamison, who heads the Western Missouri Shooters’ Alliance, a grass-roots gun rights group, argues for a controversial interpretation of a state law holding that a home can be defended with lethal force only if a deadly threat is present.

“You can’t kill a person in Missouri, or just about anywhere, for trespassing,” Jamison says. “But you can kill a burglar if your state of mind is such that you believe there is a threat to your life. That was Junior’s state of mind.”

The day after the shooting, Wilson told deputies “it occurred to me that things might get sticky, not knowing who was coming in there.”

He and many neighbors, particularly older farm families, get their news out of Kansas City. “All you see is crime,” says Byron Baty, a Wilson friend and a retired Los Angeles policeman who farms in nearby Keytesville. “People lose their perspective. They get jumpy.”

Mike Bradley, the county prosecutor who made the unpopular decision to put Wilson on trial, understands how the “sense of isolation” in a town like Hale--25 miles from Carrollton, the county seat--can heighten fears.

But a realistic look at crime here, Bradley says, would have to persuade most residents to trust in the police and use common sense.

In 1989, Carroll County reported seven violent felonies--most of them hit-and-run car assaults. Until Lineberry’s death, it had been 13 years since the county’s last alleged homicide. A typical night’s police blotter, Sheriff Joe Arnold says, runs to “tool thefts and the occasional barroom fistfight.”

Still, like the vacant house where Lineberry died, the countryside is littered with warnings to stay out--stapled to fence posts and utility poles, scrawled on barn walls. Farmers say the signs are their only legal protection from lawsuits if visitors stray onto their land and injure themselves.

Property rights have always been an abiding obsession among some landowners in the county, once a hotbed for the Minutemen, a fervent anti-communist and property rights fringe group that briefly flourished in the 1960s. Until global detente and federal gun prosecutions disbanded the secretive organization in the 1970s, a core of county farmers were attracted to its philosophy of hoarding guns to protect the heartland from a Soviet invasion.

Some farmers found more domestic enemies. A few years back, one landowner wounded a country club golfer who strayed onto his fields near the town of Chillicothe, north of Hale. Convicted of assault, jailed briefly and fined, the defiant farmer returned home and nailed up a sign: “I shot one golf pro and I’ll shoot another.” It stood until a judge ordered him to tear it down.

Deputies say there are no more than three or four county landowners willing to go that far. And until the night he confronted Lineberry, Wilson wasn’t considered to be one of them.

However, former Sheriff Swearingin had heard Wilson was “bad with trespassers.” Clifford Frock, Lineberry’s grandfather and an acquaintance of Wilson’s, says the farmer once confronted a group of loggers with a “.357 strapped to his side like Wyatt Earp.” But no official complaint was made.

Friends say the demands of his 400-acre farm would have prevented Wilson from obsessing about trespassers. When neighbors saw him, he was usually atop his old Massey Ferguson 300 combine, harvesting his cresting fields of corn, beans and milo.

Wilson’s wife, Veda, works at a sewing machine factory in Bosworth, 11 miles south. Their four children--three sons and a daughter--have left the farm, though one son, a long-distance trucker, sometimes helps out during planting and harvesting seasons.

When ill health forced Wilson’s mother, Mabel, to move out of the family homestead and in with his brother, Wayne, nearly three years ago, she took most of her possessions with her. Only a gramophone, sewing machine, several brass bed frames, some family portraits and models of World War I fighter planes remained.

They were minor heirlooms, but they held sentimental value. Last November, another vacant house owned by Wilson in Hale proper was looted of antique furniture. A month passed before he knew the items were gone, but he was angry enough to call deputies.

“He filed a report with the sheriff,” says Jamison, the Kansas City lawyer. “But of course, nothing happened. When he saw the footprints at the other house a month and a half later, he thought maybe it was the same group of thieves. He didn’t want to be a victim again.”

Jamison and Wilson’s friends believe the footprints the farmer saw were Lineberry’s. Roy Curry says that several summers ago, the boy was a regular nuisance around the old house.

“Mabel Wilson said she chased him away from the property four times,” Curry recalls.

Teen-agers say houses like the old Wilson residence are temptations for country kids with time to kill. Some go exploring on a dare or to host a beer party.

“Every kid around here’s done it,” says Jeff Grant, 23, who works at a Hale gas station. “I been in dozens. You go in a few minutes, rummage around and stuff. You’re not hurting anybody.”

Lineberry liked to forage through old houses, says his best friend, Faron Worman, in pursuit of raccoons and possums that nest in the flues of old stoves.

“It was real spur of the moment with him,” says Worman, 16. “He loved to keep coons as pets, and whenever we passed some old place out riding, he’d say, ‘I gotta go back there one of these days and see if there’s any coons.’ ”

Cheryl Lineberry, Travis’ mother, says one classmate told her that days before he died her son mused about whether he should ask Wilson for permission to set up raccoon traps in the old house. That he simply went ahead and impulsively broke in was “classic Travy,” she recalls sadly.

At Hale High School, a few of his 40 classmates called him “Lumpy.” Travis was heavy for his age, over 200 pounds. But he was also nearly six feet tall, athletic enough for a country boy’s life--hunting deer, tinkering with old cars, mock-brawling with his pals.

He roamed freely on high grass that spans 60 acres around the trailer where the family--Cheryl, Bruce, a pipeline worker, and a teen-age daughter--still lives. The house is rented, but the land is old Lineberry land.

In Hale, lineage can promise you land, but not a future. A high school junior, Travis had begun sifting through career ideas. A part-time vocational student, he wondered about electronics.

While he mulled, there were back roads to race, pranks to pull. He bought and junked a succession of cheap cars. He and Worman would roar out to the fire roads, cassette player booming out country music or the latest Guns ‘N’ Roses hits. When he felt ornery, he drove into Hale, gunned the engine and blared out 2 Live Crew, the X-rated Miami rap group.

Boredom led him into mischief. One night, Lineberry tweaked a pompous preacher by tossing several cherry bombs onto his porch. He drove his parents to distraction by pulling mice and garter snakes out of his pockets.

On that frigid Monday night in December, Lineberry, Worman and Scott Boley, a high school track star, had gone cruising in Worman’s father’s truck. They turned in on the gravel road near the old Wilson house.

“‘I just want to go up there and mess around,”’ Lineberry told Worman.

It was just after 7 p.m. Junior Wilson had been waiting inside for four nights, convinced that the prowler who left tracks outside would return.

Prosecutor Bradley says Wilson erred in failing to call deputies about his suspicions. Jamison counters that Wilson felt that “staking the place out was the strongest measure he could take.”

Scared of the dark house, Worman stayed in the truck while the other boys trudged through the snow. They shined a flashlight in the windows. Somewhere in the yard, Boley testified in a preliminary hearing, Lineberry found a crowbar and began working on the rear porch door.

Boley stayed outside while Lineberry jimmied the porch door, pried open a kitchen window and wedged himself inside. Wilson waited silently in the dark, clutching his loaded .357. At that moment, prosecutor Bradley says, Wilson had several choices: He could yell out, flick on the lights, fire a warning shot in the air, aim his gun at the youths and take them prisoner.

The farmer chose none of them.

“If he had been surprised in his own house at night, it would be a different story,” Bradley says. “But he placed himself there on purpose. There were things he could have done to prevent that boy from dying. He failed to do any of them.”

Jamison argues that Wilson had no options. Any of the choices would have made him vulnerable to an intruder’s gun. And though Lineberry displayed no weapon--a coroner did find three pen knives in his pockets--Wilson’s state of mind was fearful enough to justify waiting until the youth was almost on top of him before shooting.

“If a thief is found breaking in and is smitten that he dies,” Jamison says. “there should be no blood guilt for him.” (Exodus 22.)

Any options were gone as Lineberry reached the parlor. Wilson whipped out his .357 magnum and fired. The bullet pierced Lineberry’s chest, tearing into the right ventricle of his heart.

Wilson later told deputy Ernie Sarbaugh that “I couldn’t have missed him unless I turned around and shot the other way.”

At Lineberry’s funeral, his pallbearers huddled against a chafing wind in a graveyard not far from Wilson’s farm. Six of them, Worman, Boley and four other friends, shivered in dark jeans, Western shirts and brown leather bomber jackets.

“We wore what we’d wear when we went out on a Saturday night,” Worman recalls. “Travis would have jumped all over us for wearing suits.”

When the Lineberrys went over the signatures in the guest registry at Lindley’s, the local funeral parlor, they were surprised to find the name of one of Wilson’s sons.

Even now, bracing for the criminal trial, planning for a civil lawsuit against Wilson, her face still prone to collapsing into an anguished mask as she remembers Travis, Cheryl Lineberry marvels at the thought of a Wilson silently joining her son’s mourners.

“What he must’ve been thinking,” she wonders, “sitting out there with all those crying kids and family.”

If Wilson felt any contrition, none showed. The day after the shooting, when he went with Jamison to make a statement at the sheriff’s headquarters in Carrollton, Wilson spoke to his interrogators as if they were chewing the fat around a pot-bellied stove. If he betrayed anything, it was befuddlement about being there at all.

“You boys,” he called the deputies repeatedly, as if they were old friends. He assured them “I ain’t going to say nothing but the truth because that is the way you are going to get it anyway.”

As he finished his rambling 45-minute statement, Junior Wilson remembered one more thing from the moments before he shot Travis Lineberry, and it seemed to embody all the lost chances of that night.

“Thinking back,” Wilson said, “why, I can remember he was--yeah, I couldn’t see his face.”

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.