Michael Ivey set out to accomplish his dream of photographing America, east to west. He did. He got . . . : The Big Picture

- Share via

It’s 7:40 p.m. on a summer night and Michael Ivey has his camera set up on Huntington Beach. He’s ready to shoot. But where are all the surfers? He only has two, he needs more and time is running out. The sun has fallen to maybe 10 or 15 degrees off the horizon and is quickly turning orange.

“It’s my last shot,” he announces to the beach in general. In April, Ivey kissed his wife goodby and left his home in Mount Hope, W.Va., with $1,000 in his pocket, a station wagon full of photography equipment, and an idea.

He had a vintage 1923 Folmer-Schwing Cirkut camera that he and a partner used to shoot family and town reunions around the state. This specialized panoramic camera, which was manufactured only during the ‘20s and early ‘30s, makes a 360-degree revolution and produces prints 10 inches high and up to 6 feet long. Fewer than 100 of all Folmer-Schwings (then a division of Eastman-Kodak) are still in circulation.

“I basically wanted to cross the country,” says the 32-year-old photographer, graphic designer and white-water-rafting guide. “I was just looking for an excuse and I had this camera. And I thought the excellent thing to do would be to take the camera and take this really big picture of a really big country.”

At 7:35 a.m. April 15, Ivey snapped his shutter for the first time at the beach in Ocean City, Md. Now, several months and 30 pictures later, Ivey’s cross-country photo spree is almost over, save for the capper--a shot of the Pacific Ocean, the setting sun and surfers.

Now, where were they? “I’ve had incredible luck my entire journey,” Ivey says. “I know I’ll get the shot I’m after.”

As if on cue, a second pair of surfers shows up in wet suits carrying their boards. That makes four. Then a fifth and a sixth and, finally, a seventh appear. A pair of body boarders fall in as well. On Ivey’s left he now has an impressive row of bona fide California surfers with the pier in the background, the Pacific in front of him and the setting sun off to his right.

Satisfied, he clicks the shutter switch and as his camera begins its slow, clockwise swivel, two young girls walk into the frame. “Hold still!” he shouts. “You gotta hold still.” The girls obey, standing in knee-deep surf, as the camera, driven by a primitive clock motor, sweeps by them. It catches them before coming to a halt with the lens facing the setting sun. Perfect. The last negative is finally in the can.

“I pulled it off,” Ivey says. “It’s hard to believe. April 15th, I watched the sun come up out of the Atlantic. Now I’m watching it go down into the Pacific.”

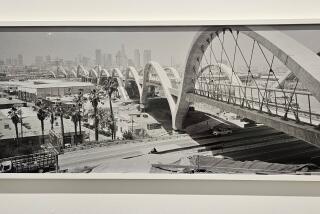

In between, Ivey caught a wide swath of the United States--a military wedding in Fort Richie, Md.; Grandfather Mountain, N.C.; Graceland; Dealey Plaza in Dallas; low riders in Chimayo, N.M.; the Grand Canyon and the Las Vegas Strip among the subjects. Some he shot to look normal. Most though, he says, “are going to come out real distorted and funky.”

As the camera shoots a curved plane, photographing a flat plane causes the image to appear to bulge forward, resulting in a sort of fun-house-mirror effect. In one particularly fanciful setup, Ivey took in 390 degrees of the Appalachia Basin in the Louisiana Bayou, causing his guide and his guide’s dog to appear at both ends of the photograph. He is planning to string all the photos together in one long, circular strip and call the installation, “150 Feet of America” (but that title, he says, may change depending on the actual length of the final crop). The circle, says the spiritually minded Ivey, “is the symbol for the soul.”

Although Ivey has an upcoming exhibition of some of his other photos at the West Virginia State Cultural Center, he is not savvy in the ways of obtaining grants. His cross-country project was funded only with the capital he could beg and borrow from friends and relatives.

“I was a super low-budget, close-to-the-bone traveler,” he says. “I slept in, on and close to my car. I had it down to where it cost me $2 a day to eat--Minute Rice and beans.”

That made for a few aesthetic restrictions as well. “I only had 30 shots. That was all I could afford,” he says, explaining that each negative for the Folmer-Schwing costs about $30, not including development costs.

Along the way, he had a run-in in a Dallas crack neighborhood, was invited to watch an American Indian sun dance and was unceremoniously escorted off a Nevada nuclear test site. With the resources to proceed one step at a time, Ivey is lining up agents and exhibitors for his project. If all goes well, he plans a better financed expedition with his Folmer-Schwing down the Pan-American Highway.

First, though, he is scrounging up enough cash to develop his prints and get him and his equipment back to West Virginia.

Not that he has any worries or regrets. “It’s definitely been a spiritual, much more internal, journey than I thought it would be,” says Ivey, who found a few days of work with a film crew and free-lance art work on commercials. And he has finished building his “coffin,” the six-plus-foot contact printer needed to make his giant prints. “After the last shot and I had it all loaded into the car, I just had this rush like, ‘Yeah, I have definitely been blessed.’ ”

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.