Lockheed to Find Out if Einstein Was Right : Science: Stanford plans to use Lockheed to test General Theory of Relativity in what could be ‘one of the great physics experiments of the 20th Century.’

- Share via

CALABASAS — Albert Einstein was one of the great minds of all time, but even he didn’t know if his General Theory of Relativity was correct.

But now Stanford University researchers hope to find out, or at least come reasonably close. Last week they took a big step in the university’s quest when they doled out a $100-million subcontract to Lockheed Corp. to build a spacecraft for what they say could be “one of the great physics experiments of the 20th Century.”

The Calabasas aerospace concern’s Missiles and Space Co. division in Sunnyvale will build the spacecraft that will carry Stanford’s long-awaited Gravity Probe B experiment into orbit in 1999--if it survives future federal budget cuts.

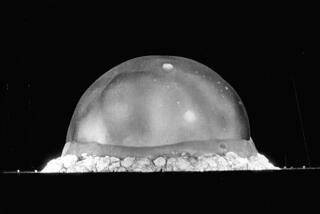

The experiment will measure how much space and time are “warped” and “dragged,” as Einstein postulated, by the presence of large gravitational masses like the earth and stars, by measuring changes in the spin of four gyroscopes.

Stanford and Lockheed scientists say the experiment is the stuff of Nobel prizes, and could confirm key tenets of the theory that has been used for most of this century to explain the way the universe behaves. If it disproves the theory, said Francis Everitt, Stanford’s principal investigator for the experiment, “all hell will break loose.”

Einstein proposed in 1906 his Special Theory of Relativity--perhaps best known for the E=MC2 equation--which explained the behavior of light. Ten years later, he put forth the revolutionary General Theory of Relativity to describe the effect of gravitational forces.

The General Theory described a continuum called space-time, and explained how gravity affects everything in the universe, producing “warp” and “drag” in space-time. Einstein theorized that objects don’t travel in straight lines because of this warpage, which was created by large gravitational bodies like planets and stars.

With the General Theory, Einstein turned Newtonian physics on its head by saying that space, time and matter were essentially the same. Previously, scientists believed they were independent, as described by the theorist Sir Isaac Newton.

But like all scientific theories, the General Theory of Relativity was just that--a theory. Although some evidence has emerged over the years to support it--such as the way light bends when passing by stars and planets--Gravity Probe B could actually measure the warping effect, if it exists.

“Confirmation or nonconfirmation at a very credible level is possible,” said Brad Parkinson, a Stanford engineering professor and project manager of Gravity Probe B.

The test was conceived in 1960 by Stanford physicist Leonard Schiff. Shortly after, the project was submitted to NASA and approved. More than 30 years later, the experiment has mushroomed into a $300-million program, but it’s taken this long for it to get off the ground.

Here’s how Gravity Probe B will work: Four super-round gyroscopes, each an inch-and-a-half in diameter, will spin on gas jets within a quartz block so they are in a free-fall, removed from earth’s gravity. The block will be frozen to minus 456 degrees Fahrenheit so that the gyros won’t be affected by temperature.

To keep the block cold, it will be put inside a metal tube called a vacuum probe, which then fits in a 7-foot-long stainless steel tank called a dewar. The dewar is essentially a high-tech thermos holding 400 gallons of super-cold helium.

Lockheed’s role in the project starts with manufacturing the dewar and the probe, which are being designed and built at Lockheed’s Palo Alto Research Laboratories, the research and development arm of the missiles and space systems division.

The equipment is to be tested on a space shuttle flight in October, 1995. Then in 1999, it will be loaded on the spacecraft that Lockheed will build, which will then be launched on a Delta 2 rocket from Vandenburg Air Force Base into a 400-mile orbit around the earth.

A powerful telescope on Lockheed’s spacecraft will help line the gyros up with the star Rigel, in the constellation Orion, chosen because of its brightness and because its position and motion is known with extreme accuracy.

The spacecraft that Lockheed will build will have to point with great accuracy at Rigel. Lockheed, which was selected for the project by Stanford and outside consultants, was no doubt chosen in part because of its extensive experience building satellites and spacecraft. Besides producing ballistic missiles such as the Trident, Lockheed is well known for its work on the Space Station Freedom project, the Hubble Space Telescope and highly advanced satellite communications systems.

Lockheed missiles and space spokesman Buddy Nelson said $8 million has been funded for the first year’s work on the Gravity Probe B spacecraft, during which engineers from Lockheed and Stanford will begin the preliminary design process.

After that it’s up to Congress to continue funding for the project.

After the experiment is launched, physicists will gather data for about 18 months. If they detect changes in the spin of the gyros, they believe this will show that large gravitational masses--in this case, Rigel--do indeed warp the fabric of space and time. That would provide by far the most solid evidence to date that Einstein was right.

If no movement is detected, physicists could be forced back to the drawing board to decide if the General Theory should be modified or even scrapped in favor of competing theories.

Scientists say the knowledge to be gained from the project will be well worth the cost. But they also say that, like previous theories that have led to the creation of everything from radios to lasers, Gravity Probe B could ultimately have an even bigger payoff.

The research conducted for the experiment has already led to certain advancements. The gyroscopes Stanford designed are the roundest objects ever built by anyone, some to within the accuracy of the width of two atoms.

The project also produced a spinoff program, funded with $2 million by the Federal Aviation Administration, that has created a navigation system that can tell the location of an aircraft within centimeters.

“What we are doing,” said Parkinson, “is unlocking science for our grandchildren.”