Giving a Way to the Will : London and Dublin work for N. Ireland peace

- Share via

On Wednesday, John Major and Albert Reynolds, the British and Irish prime ministers, issued a historic and courageous joint declaration on the future of Northern Ireland.

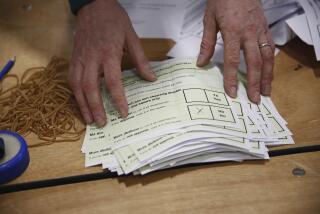

The British government agreed “that it is for the people of the island of Ireland alone, by agreement between the two parts (Northern Ireland and the Republic of Ireland) respectively, to exercise their right of self-determination on the basis of consent, freely and concurrently given, North and South, to bring about a united Ireland, if that is their wish.” The Irish prime minister confirmed, as expected, that he would “support proposals for change in the Irish Constitution which would fully reflect the principle of consent in Northern Ireland.” More important, he committed Ireland to a variety of moves aimed at making unification less abhorrent than it now is to the unionist party in the north. Thus, “the Taoiseach (Irish prime minister) will examine with his colleagues any elements in the democratic life and organisation of the Irish State that can be represented . . . as a real and substantial threat to (the unionists’) way of life and ethos . . . and undertakes to examine any possible ways of removing such obstacles.” Broadly, the allusion is to the place of Roman Catholicism in the life of the Irish Republic. Though Catholicism has had no official status in Ireland since 1972, divorce is still illegal there. This may now change: A referendum to legalize it goes before the voters next fall.

One might think that nationalists and unionists in Northern Ireland who wish, respectively, union with Ireland or continued union with Britain would regard as immediately decisive what the British and Irish governments have determined in this regard, but it will not be so. Even optimists do not believe that the London declaration will be decisive immediately, and pessimists scoff that it never will matter at all.

We choose to side with the optimists. The support that Reynolds and Major enjoy in Northern Ireland is not to be underestimated. They have almost certainly brought the more moderate of the two unionist parties, James Molyneux’s Ulster Unionist Party, into dialogue with the nationalists. Both of the nationalist parties--the Social Democratic Labor Party and (the major new development) Sinn Fein, the political partner of the Irish Republican Army--are prepared for the same dialogue. Even if some in the IRA and in the unionist paramilitary organizations attempt to sabotage the declaration, as is to be expected, this level of official support is not trivial. Behind that official support, of course, and behind the Dublin-London rapprochement itself, stands the will of the vast majority of the population in Northern Ireland itself to seek reconciliation. In the long run, this is the majority whose will all may be forced to respect.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.