Payments Urged for Radiation Test Victims : Government: Energy Secretary O’Leary’s call is first indication that U.S. is willing to acknowledge liability.

- Share via

WASHINGTON — The U.S. government should compensate victims of radiation testing conducted as part of its Cold War nuclear program, Energy Secretary Hazel O’Leary said Tuesday as disclosures mounted about extensive experiments involving humans as often-unwitting subjects.

In an interview on Cable News Network, O’Leary said: “We ought to go forward and explain to the Congress what has happened and let the Congress of the United States and the American public determine what would be appropriate compensation.”

O’Leary’s comments marked the first time the federal government has indicated it is willing to acknowledge liability for possible harm done by hundreds of government-funded tests conducted from the late 1940s into the ‘70s. Government compensation for test victims across the country could total hundreds of millions of dollars, but could end costly lawsuits brought by several citizen groups.

O’Leary said that up to 800 people were subjected to the experiments and exposed to potentially harmful amounts of radiation, some apparently without their informed consent.

Under O’Leary, the department has vowed to “come clean” on the secrets of nuclear testing. Her department and an independent task force it has named are conducting investigations of dozens and possibly hundreds of government-sponsored experiments in which humans were subjected to radiation.

O’Leary’s promise to unmask the experiments has set off a flurry of news reports detailing human experiments, although few names have emerged because many of the consent forms and logs of the experiments have been lost.

The Energy Department late last week established a toll-free phone line, (800) 493-2998, for individuals to call if they believe they have been subjects in a test involving radiation. Since Friday, the Department has received roughly 100 calls a day.

In recent months, reports on radiation testing have cited experiments that include conducting nuclear tests over populated areas and injecting patients, including newborn babies, with plutonium and radioactive iodine.

The Boston Globe has reported that in one experiment between 1946 and 1956, at least 49 mentally retarded teen-agers were fed radioactive food in a study of the human digestive process. The tests, funded partly by Quaker Oats Co. and the U.S. Atomic Energy Commission, used radioactive forms of iron and calcium to determine if a heavy diet of cereals slowed digestion of those minerals, the newspaper said. The experiments were conducted by researchers from Harvard University and the Massachusetts Institute of Technology.

Asked Tuesday if the various disclosures leave the government vulnerable to lawsuits, O’Leary said: “My view is that we must proceed with disclosing these facts and information regardless of the fact of whether it opens the door for a lawsuit against the government. Many have suggested, and I tend to agree personally, that those people who were wronged need to be compensated.”

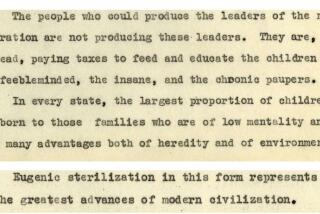

In the latest indication that scientists even at the dawn of the Atomic Age had reservations about the human experiments, a report Tuesday said that a top radiation biologist warned in 1950 that the research had “a little of the Buchenwald touch,” a reference to a Nazi concentration camp where medical experiments were carried out on prisoners.

Dr. Joseph Hamilton, who worked for the U.S. Atomic Energy Commission, made the analogy to Buchenwald in a memo outlining his concerns about experiments designed to gauge levels of radiation that would injure soldiers.

According to the New York Times, which quoted from Hamilton’s memo in its Tuesday editions, Hamilton warned that commission officials “would be subject to considerable criticism” for conducting experiments that exposed people to potentially harmful doses of radiation.

If Congress approves compensation for subjects of radiation experiments, the payments would probably ease the legal barriers for many who have sought reparations from the U.S. government. Courts have frequently turned away suits in such cases, arguing that the government could not be sued for discretionary acts performed in good faith.

At the same time, however, a decision to compensate for radiation experiments could place strict limits on the amounts the victims could receive.

One expert suggested such a decision also could give momentum to hundreds of claims that have been filed by workers at U.S. nuclear production plants, many of whom allege they have been exposed to unsafe levels of radiation.

“If we’re going to engage in a debate over what to do with (unwitting victims of) dangerous radiation, we should include in their numbers those who were exposed on the front lines of the Cold War--the nuclear production workers . . . ,” said Paul DeMarco, a Cincinnati attorney.

“These people have not received the compensation due,” DeMarco said. “What is worse? Someone completely unaware that they’re being subjected to radiation? Or someone who’s brought into a nuclear facility, given a radiation badge, given regular urinalyses and led to feel safe when he’s not?”

In only one major case has the federal government approved compensation for large groups of individuals affected by the U.S. nuclear program.

In 1988, Congress approved a compensation bill for three groups of people affected by the nuclear weapon program: Those who could prove that they were downwind from open-air nuclear tests in Nevada and developed certain kinds of cancers received maximum benefits of $50,000; soldiers and other defense workers who were on duty in Nevada and the Pacific Island test sites when bombs went off and developed certain cancers were awarded benefits of no more than $75,000, and those who worked in uranium mines for the U.S. nuclear program and developed certain cancers could receive a maximum of $100,000 in benefits.

Roughly 1,000 individuals have been compensated under the program, for which $182 million has been set aside for the year that began Oct. 1.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.