Fear Clouds Search for Genetic Roots of Violence : Sociology: Many say studies could open the door to abuses and racism. Scientists are sharply divided.

- Share via

As gun detectors become standard furniture in schools and some children learn to fire automatic weapons before they learn to drive, Dr. Markku Linnoila is struggling to unravel a great mystery of human behavior: What transforms innocent little children into brutal teen-agers and adults?

Across America, hundreds of other scholars are on a similar quest, frantically searching for the roots of modern violence. Most are pursuing the obvious leads: poverty, parental neglect, lack of education, drugs, guns and TV violence.

Not Linnoila. He is hunting for clues in genes--and triggering great controversy while he is at it.

In his laboratory at the National Institutes of Health, the soft-spoken native of Finland has spent 13 years immersing himself in the intricacies of the brain chemical serotonin. By examining the spinal fluid and blood of more than 1,000 Finnish prisoners--including 300 violent offenders--he says he has proved over and over again that people with low levels of this neurotransmitter are prone to impulsive, violent acts, especially when they abuse alcohol.

Now, Linnoila is searching for “vulnerability genes” that create this serotonin deficit. His goal: to be able to predict who might become violent, and then to prevent it--either with programs to help these people change their behavior or, if that doesn’t work, new drugs.

At a time when the U.S Centers for Disease Control has declared that violence is America’s most pressing public health threat, Linnoila’s work raises some of the most intriguing--and politically volatile--questions in medical research today: Are some people biologically or genetically predisposed to violence? Could traditional medicine hold clues, even tiny ones, to making streets safe again?

“We are trying,” Linnoila explains simply, “to address this public health problem with an open mind.”

But not everyone’s mind is so open.

His work challenges long-held assumptions that social and environmental factors--poverty, joblessness, discrimination, lack of education--are the sole causes of crime and violence. And there is bitter controversy over whether science should even attempt to answer the questions raised by his research.

Critics say research like Linnoila’s is dangerous, that it holds too much potential for abuse. The biggest fear is that the studies will be used to discriminate against people of color, particularly African Americans. This is because blacks are disproportionately represented in arrest statistics; the federal government reports that African Americans, who make up about 12% of the population, account for 45% of all arrests for violent crimes such as homicide, rape and robbery.

Thus, scientific pursuits have become entangled in delicate discussions of race. Social tensions are spilling over into the laboratory. Not surprisingly, the debate sometimes gets emotional.

“We know what causes violence in our society: poverty, discrimination, the failure of our educational system,” said Dr. Paul Billings, a clinical geneticist at Stanford University who has spoken out against such research. “It’s not the genes that cause violence in our society. It’s our social system.”

Counters Adrian Raine, a USC psychologist who has reviewed all published research that attempts to link biology to violence: “It is irrefutably the case that biologic and genetic factors play a role. That is beyond scientific question. If we ignore that over the next few decades, then we will never ever rid society (of violence).”

Many Factors at Work

It is a classic nature-versus-nurture debate--one that might be confined to the ivory tower, if it were not for the dreadful toll that violence is taking on America.

The United States leads the industrialized world in murder, with an annual rate of homicide four times that of Scotland, the country with the next-highest rate. Murder is responsible for more deaths among young black men in America than any other cause, and Latino men are three times as likely to be killed as whites. According to the CDC, homicide is the nation’s 11th-leading cause of death.

Theories abound concerning the reasons for this upsurge: Poor parenting. Television violence. Poverty. Discrimination. Substandard housing. Inadequate education. Easy access to guns. Drug abuse. Genetics and biology. The truth is, all these factors are at work, but no one really knows how they play in combination with one another. There are many questions. Answers are scarce.

“There are lots of things that we don’t know,” Yale University sociologist Albert Reiss said. “What is it that accounts for the fact that we have more interpersonal violence (than other nations) and that it is disproportionately among blacks? That’s a puzzle. And why is it that women have so much less homicide, but suicide ranks higher? If you think we know the answers to all those questions, then there is no reason to do research.”

Although rational voices agree that biology and genetics probably play a role in causing violence, what they cannot agree on is this: How much of a role? Or is this intellectual territory better left unexplored?

Last year, the National Research Council stepped into the fray and gingerly sided with the argument made by Raine of USC. As the research branch of the National Academy of Sciences, the most prestigious scientific group in the nation, the NRC brought together 19 of America’s most prominent academics to explore every aspect of the nation’s violence problem.

In a massive 464-page report titled “Understanding and Preventing Violence,” the scientists recommended that along with traditional research into the social causes of violence, biomedical research into violence should be increased.

The language was cautious, noting that “evidence of a genetic influence specific to violent behavior is mixed.” But the message was clear: The human body may hold clues to what makes people violent. And scientists ought to pursue them.

Aside from genetics, the NRC cited other important biological leads, including studies that show certain brain abnormalities are linked to violent behavior. And it suggested new drugs might be developed to prevent violent behavior “without undesirable side effects.”

Yet using medicine to “cure” violence is precisely what opponents find so abhorrent.

Among the most vocal critics is Dr. Peter Breggin. As founder of the Center for the Study of Psychiatry in Bethesda, Md., Breggin has made a career of fighting medical approaches to social problems. He envisions a frightening scenario in which government-funded genetic screening programs will label inner-city youngsters at risk for becoming violent, and then dope them up in what he calls “a massive drugging of America’s children.”

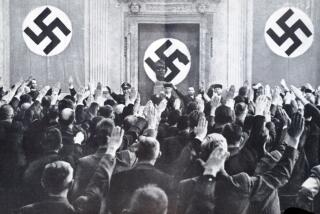

Not one to mince words, Breggin compares attempts to find genes for violence to the horrifying genetic experiments that took place during the Nazi Holocaust. “It’s like if you go into the concentration camps and see how bad the Jews are doing, to look for genetic factors for it!” he exclaims. “This is biomedical social control.”

If history is any guide, Breggin may have reason to be fearful. Americans have long been fascinated with biological explanations for violence, and the research cannot escape its own sordid history, a legacy of one debunked theory after another.

During the early 20th Century, advocates of eugenics--a movement that asserted society should encourage breeding by those with “good traits”--claimed that certain immigrant groups had higher crime rates because they came from genetically flawed stock. Advocates of eugenics believed that criminal tendencies were linked to what was then called feeblemindedness. While eugenics was in vogue, more than 30 states passed laws providing for the sterilization of the feebleminded or insane.

More recently, in the late 1960s and early 1970s, there was a flurry of interest around scientific reports that boys born with an extra Y chromosome were destined to become violent. The studies were ultimately discredited, but not before researchers in Boston began screening newborn boys--a program that was canceled amid public outrage. Jonathan Beckwith, a Harvard University geneticist, said: “The whole premise of the study was based on terribly faulty science.”

Yet over the years, science has developed a significant--if scattered--body of evidence that indicates some people are indeed biologically prone to violence. For instance, studies have shown that a disproportionate number of murderers have suffered from head injuries. Hypoglycemia--low blood sugar levels--has been linked to violent and aggressive behavior. So has the male hormone testosterone, in high concentrations.

Sophisticated brain imaging has pinpointed differences in the prefrontal cortex--the region of the brain believed to control social behavior--of violent criminals. Other studies have suggested that people with low levels of “arousal”--heart rate, sweat rate and electrical activity of the brain--are more likely to commit violent crimes.

Controversial History

Not all of these biological differences have their roots in genes, and so far research into the links between genetics and violence has been limited.

But recent advances in molecular biology are opening up vast--and as yet largely untapped--possibilities for studies into how genes affect behavior, including violence. This field, “behavioral genetics,” has been fraught with controversy; claims of genes for schizophrenia, manic depression and alcoholism have all either been disproved or come under severe criticism. Some say the same will undoubtedly be true of any attempt to find a gene for violence.

Others worry about how the research will be used.

“Let’s just assume we find a genetic link (to violence),” said Ronald Walters, a political scientist at Howard University in Washington. “The question I have always raised is how will this finding be used? There is a good case, on the basis of history, that it could be used in a racially oppressive way, which is to say you could mount drug programs in inner-city communities based upon this identification of so-called genetic markers.”

So far, just one study has made a connection between a specific gene and violence. In October, a team of Dutch scientists reported that they had found a genetic mutation in a family whose men had a long history of violence--including a rape that occurred 50 years ago, two arsons and an incident in which a man tried to run down his boss with a car after receiving a negative performance evaluation.

These men, the researchers found, had abnormal genes that code for enzymes that help break down the brain chemical monoamine oxidase, which could cause someone to respond violently to stress if allowed to build up in high concentrations. But the study’s authors--well aware of the controversy their work might engender--were quick to caution that their discovery of the so-called aggression gene applied only to the one family they studied, and that the genetic defect was probably not widespread.

The serotonin deficit that Linnoila is investigating is far more commonplace; he estimates it may be present in as many as one out of every 20 men. But, Linnoila adds, there are more than 20 genes that could control the manufacture of this brain chemical. And it will be at least another decade before he understands how they work together--in connection with other factors, such as alcohol abuse or poor parenting--to make people violent.

“The low serotonin turnover as such does not make anybody a violent criminal,” Linnoila said. “It is simply a predisposing factor. . . . The challenge is really to understand how the genes and environment interact.”

Uproar Over Research

No scientist has suggested that there is a single gene for violence, or that biology alone can explain the broad swath of crime cutting through American society. But Linnoila and others do say these studies could provide science with clues about why people become violent in certain situations--and how to prevent it. Even if the research applies to only a small number of people, advocates argue, it will still be worthwhile.

“Violent behavior is a problem for society,” said Kenneth K. Kidd, a geneticist at Yale University. “And there is growing evidence that some small component--I have no idea how big yet--of violent behavior has a genetic basis. So I think it is worth trying to understand what causes that and trying to understand how we can minimize it.”

Dr. Frederick Goodwin thought so too, but he was not nearly so careful in his choice of words as Kidd, and it got him into trouble.

In the 1970s and 1980s, Goodwin, a respected psychiatrist, conducted studies into the connection between serotonin and violence. Goodwin later became director of the now-defunct federal Alcohol, Drug Abuse and Mental Health Administration. Two years ago, while still in that job, he called for government scientists to embark on a large-scale violence initiative that would include biomedical research.

But Goodwin sprinkled his speech with several remarks that were later interpreted as racist, including one that suggested studies involving monkeys might prove useful in understanding violence in humans. The comments sparked a huge uproar, the violence initiative was scuttled and amid the fury, the NIH convened a special panel to review all its violence-related research.

The panel has not yet made its recommendations, but members say it is likely to suggest the NIH expand its research into the social causes of violence. Goodwin, meanwhile, was forced to resign his post with the alcohol and drug abuse agency and now serves as director of the National Institute of Mental Health. He declined to be interviewed.

But the controversy has failed to subside.

Among those it has snagged is David Wasserman, a 40-year-old lawyer and research scholar at a University of Maryland think tank. Wasserman organized and scheduled a conference on genetics and crime for October, 1992--eight months after Goodwin made his ill-fated remarks.

Although the NIH had agreed to foot the $78,000 bill for the conference, it yanked the funding after Breggin and others complained about the conference. Wasserman was forced to cancel the meeting, but the university appealed and the money has since been reinstated. The conference will be held, Wasserman says, but its agenda will be nowhere near as broad as the one he first envisioned.

That is because the researchers he invited are now afraid to discuss their work.

“I had scientists who were invited to the conference telling me that they were going to tone down what they were going to say because they didn’t want (their funding) to be placed in jeopardy,” he said.

For scientists interested in the biology of violence, any public pronouncements are fraught with danger. Sarnoff Mednick learned that lesson long ago.

Mednick is a USC psychologist who in the late 1970s conducted a landmark study of genetics and crime. His was a classic genetics study. It relied not on the sophisticated techniques of molecular biology but on a painstaking analysis of the criminal records of more than 14,427 adopted children in Denmark between 1927 and 1947. (Scandinavian nations are particularly suited to genetic studies because their populations are homogeneous and because they keep excellent records.) He compared these records with the criminal records of the children’s biological and adoptive parents.

Mednick found no evidence that children inherited a tendency toward violence. But he did find that youngsters were more likely to commit property crimes, such as theft, if their biological parents had also committed property crimes. And, like Linnoila, he found himself caught up in a heated political debate.

“People were out of their minds trying to deny that this could possibly exist . . . ,” he said. “When I presented the paper orally at the American Assn. for the Advancement of Science, there was a mob scene, with the press running after me and me running away. I was amazed.”

A Public Health Issue

In 1983, Mednick proposed a large-scale study that would have measured arousal--sweat rate, heart rate and brain electrical activity--in juvenile delinquents. The object was to predict who would become repeat offenders. He says his plan received initial approval from the U.S. Department of Justice, which was to fund the study, and that he had the cooperation of judges in San Diego, where the research was to have been conducted.

But the funding was withdrawn, Mednick said, after a Washington newspaper columnist published an article comparing his proposal to “something cooked up by the Nazis’ Dr. Mengele.” Now, 10 years later, Mednick is about to embark on the same study--in Australia, where the political opposition is not as great.

Mednick is morose about the future of this biomedical research into violence. “It’s kind of hopeless,” he said. “Nobody permits the studies to be done. Nobody permits the conferences to be held.”

And like most others in the field, Mednick tries to shield his work from publicity. “I think most of the people who are doing serious work on this try to avoid it,” he said in a recent telephone interview. “Like I was trying to avoid this phone call for some time.”

Linnoila, too, worries that anything he says will be misconstrued. He fears he will be branded as “one of these crazies,” and he chooses his words with caution. He is careful to say that, in his vision, drugs would be used to control violent behavior only as a last resort, after other programs had been tried and failed. And he offers--without being asked--that he does not consider his research “an ethnic issue.”

But he believes fiercely that science may hold at least some clues to curing America’s violence epidemic, and that his own research is crucial to the public health of a nation at risk.

“Our critics paint these nightmare scenarios based on their own imaginations . . . that somewhere there is a bogyman who wants to immediately start drugging people, and I don’t see that,” he said. “I think that we have a very significant problem with interpersonal violent behavior. And it behooves us, if we are serious about this, to try to understand how to prevent it.”

Violence and the Brain

Dr. Markku Linnoila of the National Institutes of Health has spent the past 13 years researching serotonin, a neurotransmitter--or brain chemical--that modulates emotion. Linnoila’s research has repeatedly shown that people with low levels of serotonin (pronounced SER-uh-TOE-nin) are prone to impulsive, violent acts. Linnoila is now looking for genes that create this serotonin imbalance. Finding these genes could help scientists predict who might become violent--and give them preventive treatment.

Background

The brain has 10 billion to 100 billion nerve cells. Messages between cells are communicated by both electrical and chemical processes. Here is a look at how the chemical process works:

The Messengers

A. Nerve cells, called neurons, contain tentacle-like structures known as axons that carry messages. Others, known as dendrites, receive messages.

B. The axons of one nerve cell are separated from the dendrites of another by a tiny gap called a synaptic cleft, or synapse.

C. Messages are transmitted across the synapse by the various neurochemicals transmitters.

D. Many researchers believe that the neurotransmitter known as serotonin plays a key role in a number of emotions. Imbalances in serotonin levels have various effects; low levels have been tied to depression, suicidal behavior and aggression while large amounts can bring on emotional highs, including mania.

What is Serotonin?

Serotonin, which is converted from an amino acid called tryptophan, is a naturally occurring chemical found in the brain, blood and other parts of the body. It can also be produced synthetically. In the brain, it is one of at least 40 chemicals that serve as messengers between nerve cells.

Research by NONA YATES / Los Angeles Times

Sources: World Book Encyclopedia, Times files.

The High Cost

Violence is one of the United States’ most pressing public health threats, according to the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Some of the sobering figures:

* THE TOLL: Homicide is the nation’s 11th leading cause of death, and the leading cause of death for young black men. It is the second leading cause of death for people ages 15 to 24.

* TEEN-AGERS: Firearms are responsible for the deaths of more U.S. teen-agers than are all diseases combined.

* THE GUN’S ROLE: More than 60% of all murders are committed with guns. At least 80% of the cost of treating firearms injuries is paid by taxpayers.

* THE HOSPITAL SCENE: Each year, more than 2 million Americans suffer injuries as a result of violence, and more than 500,000 are treated in emergency rooms.

* THE COST: By some estimates, the nation spends as much as $18 billion each year caring for victims of violence; by comparison, $10 billion was spent last year to treat people infected with the AIDS virus.

The Debate

As academics across the nation struggle to understand the causes of violence and how to prevent it, some scientists are looking to the human body for clues. There is scientific evidence that biology and genetics play some role in violent behavior. But biomedical research into violence is highly controversial, and some critics would like to see it quashed.

“It’s like if you go into the (Nazi) concentration camps and see how bad the Jews are doing, to look for genetic factors for it! This is biomedical social control.”

--Dr. Peter Breggin, who opposes attempts to find genes for violence.

*

“Our critics paint these nightmare scenarios . . . that somewhere there is a bogyman who wants to start drugging people. . . . I think we have a very significant problem with interpersonal violent behavior. It behooves us, if we are serious about this, to try to understand how to prevent it.”

--Dr. Markku Linnoila, who believes that science may be able to find some clues to violence.