The Morality of Selective Intervention : Foreign policy: We should act only where we can assist a positive outcome--in Bosnia, say, but not in Rwanda.

- Share via

The life of a Rwandan is as precious as the life of a Bosnian. The maiming of Angolans and Sudanese is no more tolerable than the maiming of Muslim Bosnians in Gorazde. We should value human lives equally but this does not compel the United States to intervene with military force in every place where individuals and groups are persecuted--or nowhere at all.

The argument is specious that it is immoral to intervene in Bosnia to stop the carnage while we do not send military force to save lives in Rwanda. Military intervention by the United States to save lives in places of civil strife will always stem from a perception of our strategic interests, the feasibility of action, political support for the intervention and, yes, humanitarian concerns.

We need not be and cannot be consistent in our response to ethnic violence. Our economic and military resources are not sufficient for us to be the world’s policeman. Political capabilities at home do not permit the mobilization of support where American citizens and leaders alike do not perceive any strategic interests at stake. Political capabilities abroad do not allow us always to form alliances for military intervention where other countries do not share our concerns and do not see their interests at stake, as they did in the Gulf War.

It is wrong to argue that if we cannot help all people we should help none, because to choose is morally repugnant. Indeed, we sent troops to make possible the delivery of relief supplies in Somalia in part because it was logistically feasible to do so. The United States was unable and unwilling to mount a similar effort in the Sudan or in Angola during their civil wars. Intervention in Somalia went sour as the United Nations’ mission changed. But selective intervention should not be given a bad name.

NATO and U.N. troops are already in and near Bosnia. We have declared our commitment to protect safe zones in Bosnia. NATO, the United States, and the United Nations have been deeply implicated in the negotiations in Bosnia for more than two years. This is an area where we can perhaps alleviate the suffering of victims by using military might. We may choose not to do so because of military and political consequences. However, it is reasonable to think that limited military intervention could make a difference.

Our national interests include our cherishing of peace and the diminution of torture and aggression around the world. We cannot always bring these interests to fruition, especially where overriding strategic interests are not at stake. Indeed, it is arguable whether any deep strategic interest is at stake for the United States in Bosnia. A greater Serbia is unlikely to threaten Europe beyond the areas where Serbs live. The conflict in the former Yugoslavia probably can be contained within the boundaries of that destroyed state. Nor will ethnic violence in Bosnia inspire such violence elsewhere; people in the Caucasus do not seem to require examples to emulate.

Nonetheless, our interests, if not our national security, are engaged in Bosnia. We can have effect there in concert with NATO allies. Whether we want to exert ourselves militarily is a matter to be decided. But to argue, as some do, that unless we intervene for peace everywhere we cannot act in Bosnia is the height of folly and itself is a morally specious argument.

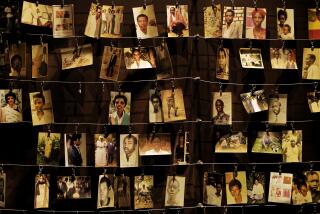

We do need to anticipate more Rwandas, if not more Bosnias--to be prepared for the large-scale ethnic strife that is, unfortunately, on the horizon elsewhere in Africa. It takes too long to mobilize international efforts, whether they be relief or military ones. Rwanda has shown this all too starkly.

Since the United States and other powers will always look at their intervention selectively, we should seriously consider helping to build a United Nations anticipatory force ready to intervene when genocide occurs. Thousands of lives might be saved by timely intervention.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.