Experimental Transplant Gives Girl a New Life : Health: Procedure performed at CHOC may help other cancer patients who cannot find donors of matching bone marrow.

- Share via

ORANGE — A 6-month-old girl who is one of the first people in the United States to undergo an experimental bone marrow transplant is “doing very well,” the Children’s Hospital of Orange County reported Thursday.

The procedure, which involves transplanting megadoses of unmatched bone marrow cells, was performed at CHOC in November on the girl, whose family is from Glendale.

Scientists said the procedure may hold new hope for cancer patients unable to find relatives or other donors with marrow that genetically matches their own. The findings of the Italian and Israeli research team that pioneered the unmatched marrow technique--published in the journal Blood--were hailed Thursday.

The procedure uses seven to 10 times the normal amount of donated marrow cells, which allows the patient to regenerate a immune system at a faster rate. And because the marrow used is unmatched, it is stripped beforehand of cells that would cause the body to reject the transplant, the researchers reported.

The transplant was performed by a team of physicians led by Dr. Mitchell S. Cairo, director of bone marrow transplantation at CHOC. Cairo, who had read about the procedure, thought it might help the patient, Aida Jacinto, whose prognosis “was dismal.”

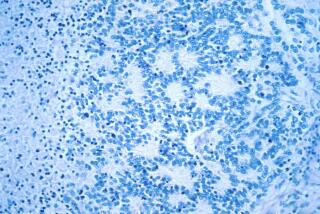

Aida was 2 weeks old when doctors at Childrens Hospital Los Angeles found that she suffered from acute lymphoblastic leukemia, said Renna Killen, CHOC’s bone marrow nurse coordinator.

Conventional chemotherapy temporarily put her cancer into remission, but the disease returned and could not be fought off a second time, Killen said.

In order to try more intensive chemotherapy and radiation, the girl needed a source of marrow that the doctors could use to replenish her immune system, which would be destroyed along with cancer cells by the proposed treatment, Killen said. But none of the girl’s relatives had matching marrow and a worldwide search failed to find a compatible marrow source.

Physicians at CHOC, where Aida had been referred for the transplant, could not extract her own bone marrow and save it to be re-injected later because the marrow was too cancer-ridden to be cleansed, she said.

Cairo thought of the research he had read on the treatment pioneered by biophysicist Yair Reisner of the Weizmann Institute in Rehovot, Israel, and Dr. Massimo F. Martelli of the Polyclinico Monteluce in Perugia, Italy.

He then explained Aida’s poor prognosis and the treatment’s risks to her parents.

A bone marrow transplant is not itself therapeutic--it does not kill cancer cells. That is achieved with very high doses of radiation and chemotherapy, which are used in an attempt to wipe out the last vestiges of cancer cells in leukemia patients who have not improved after undergoing lower doses of chemotherapy.

But these high doses also kill the healthy bone marrow, the source of both white and red blood cells. Without the marrow, a patient will die within a few days. A transplant gives the patient a new immune system.

Gloria Martinez, 37, said she and her husband, Ramon Jacinto, 41, understood the danger for Aida.

“We wanted to save her life,” Martinez said. “I said, ‘OK, go ahead.’ I was excited for her.”

In mid-October, Aida underwent intense treatment, including chemotherapy and full-body radiation. And doctors collected bone marrow from Martinez.

“It looks like I’m giving her life a second time,” Martinez said Thursday of the role she played.

Cairo said marrow was extracted from Martinez’s hip bones and a hormone was injected into her to stimulate the production of stem cells and to trigger their release into her bloodstream. Blood was then drained from Martinez’s arm, he said, and the stem cells, which manufacture blood cells, and white cells were removed. The blood was then returned to Martinez.

The stem cells were infused on Nov. 4 and 5 into the girl, he said, and served to accelerate the reconstruction of her immune system.

Another important part of the process, Cairo said, called for removing T-cells from the donated marrow that could otherwise cause a serious adverse immune reaction in the girl and death through rejection of the transplant.

Nearly a month later, Cairo said, the graft has taken hold, is producing blood cells normally and there is no sign of cancer.

He cautioned, however, that because the procedure is so new, the long-term outcome is unknown.