WESTSIDE COVER STORY : Testing Their Olympic Mettle : Top Westside Athletes Dream of Glory as They Sweat Out Training for ’96

- Share via

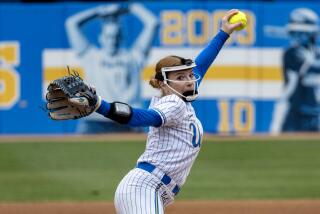

With a loud “ping” of her aluminum bat, the hitter sends the yellow ball screaming across the infield. Nicole Odom gently scoops up the missile and flings it to first base with a quick step-turn-pivot and throw. The lanky UCLA shortstop digs her cleats into the soft dirt as the next victim steps up to the plate.

Today, Cal State Long Beach. Tomorrow, the world.

Odom, a women’s softball star, is one of a handful of world-class athletes who live on the Westside and train here for the 1996 Summer Olympics. For the most part, they are hitting, fielding, sailing, running and spiking in obscurity.

They are the architect in the next cubicle, the student on the other side of your college English class, the man who sells you lumber at Home Depot.

With the torch-lighting in Atlanta more than a year away, athletes still face months of training, stomach-knotting Olympic trials and--in many cases--relentless day jobs to make ends meet. For now, they can only dream of the adoring crowds, the international pageantry--and the medals.

A look at a few Westsiders working to make that dream a reality:

The Sailor

Quick--name four famous sailors. Besides Blackbeard, Long John Silver, Captain Hook and Popeye, does anyone come to mind? Maybe Dennis Conner of America’s Cup fame, but after that, public recognition for sailors ranks slightly below Nobel Prize-winning economists, hammer-throw champions and tuna fishermen.

“It’s kind of frustrating to me,” said Bob Little of Santa Monica, a world-class boatman who went to the 1992 Olympics in Barcelona, Spain, as an alternate in the two-man sailing competition. “When I tell people what I do, they don’t even know it’s in the Olympics.”

While other kids were tossing the pigskin and shooting hoops, Little was harnessing winds in the Pacific. Born in Boston, he grew up in Santa Monica and has been racing since he was 11 years old. He still sails three or four times a week out of the California Yacht Club in Marina del Rey and at the U.S. Sailing Center in Long Beach.

When he’s not at sea, Little, who is single, works as an architectural designer for the Jerde Partnership in Venice, helping draw up mixed-use office, entertainment, retail and housing developments.

“I started out with junior sailing, with one-man boats, eight feet long,” Little said. “We used to race those here in Marina del Rey. We’d travel to San Diego and race the other kids in the other yacht clubs.”

The 27-year-old Little and his partner, Mike Sturman of Newport Beach, compete in the two-man 470 class, racing an approximately 16-foot sailboat. Sturman runs the helm, concentrating on the boat’s speed and performance. Little performs as the crew, calling tactics and serving as the team’s eye.

Partners since 1990, Little and Sturman have been ranked No. 1 or No. 2 in the United States for the last five years in their class. This month they represent the United States in the Pan American Games in Argentina.

In competition, teams maneuver their boats through five separate legs of the course. Depending on the wind, the trapezoidal course is lengthened or shortened so most boats finish the track in 50 to 60 minutes.

Fighting the winds, trimming the sails and hurling one’s body like a counterweight around the boat can be physically exhausting. Course length ranges from three-quarters of a mile to a mile and a half.

“The toughest part about sailing is you’re required to do all the physical demands with all the mental requirements: the wind, the waves, the other competitors and the weather,” said Mike Segerblom, USC sailing coach and executive director of the U.S. Sailing Center in Long Beach. “The total weight of the boat is less than the weight of the crew, so every movement they make is a major influence.”

Segerblom coached Little at USC and continues to monitor his career. “Bob was a top All-American sailor in college and he’s put in all the time and effort since then.”

While some athletes can profit from their sport, sailors can be washed up in an ocean of red ink.

The team must raise $45,000 a year in donations just to stay afloat. That’s why Little, when he’s not working as an architectural designer, sailing or working out in the weight room, is meeting with sponsors, Olympics committee members and others who can keep him in the water.

“You need money to compete at a high level,” Little says, “but if you have the talent, the money’s available.”

The Runner

One-point-five seconds.

It is the time it takes to blink twice. Or to switch channels on the remote control.

It is the time that separated Christian Cushing-murray from the 1992 Olympic games.

The astounding fact about Cushing-murray is not that he missed making the American team, it’s that he ever got close.

When he graduated from North Hollywood High School in 1985, no one thought he would become a champion college miler. At UCLA, he never qualified for the nationals or won a Pac-10 championship. Today, the 27-year-old Playa del Rey runner may be the best American track star you’ve never heard of, certainly the Westside’s best chance to qualify for the 1,500 meters.

“From his performance in college to where he is now, I don’t know any other runner that has ever come as far as Christian has,” said Joe Douglas, coach and founder of the world-famous Santa Monica Track Club where Cushing-murray trains.

During the 1992 U.S. Olympic trials, Cushing-murray finished fifth, just 1.5 seconds from making the team. That’s only half of the story. “In the finals, a guy fell down in front of him,” said Douglas. “Had that not happened, he would have made the U.S. team.”

The slim, bearded athlete admits 1992 was a disappointment. But he seems to have put the experience in perspective.

“I ran a very tentative race,” said the 5-foot-11, 140-pound runner. “Having run in the trials, now I know how close I am. My goal in 1996 is to make sure that anything that happens, I have to be good enough to overcome it. I can’t let those things distract me from the primary goal.”

To get to the 1996 trials in June, he will have to post a 3:41.86 time in the 1,500 meters. With a personal best of 3:37, qualifying should be easy. In 1994, though, Cushing-murray slipped to ninth in the American rankings, a drop he credits to significant lifestyle changes.

Last summer his wife, Kathleen, gave birth to their first child, Nathaniel. He has since adjusted to raising a newborn and he left his job at a department store for a less stressful job at Home Depot. The building-supply store is one of several Olympic sponsors that pay their athlete-employees full-time wages for part-time work.

The job allows Cushing-murray to run 10 to 12 miles each day, six days a week. The results speak for themselves, with a victory at the Super Bowl 10K in Redondo Beach in January and a fifth-place finish against world-class talent in the mile race at the Sunkist Invitational in February.

He said that when he graduated from UCLA in 1989, he wanted to tour the world and make a living as a “rabbit”--being paid to run a quick early race to set the pace for other milers.

“I didn’t really run fast until my senior year (at UCLA), and I didn’t do it consistently,” he said. “What really made me change my mind was coming out to the Santa Monica Track Club and training with Joe Douglas in 1990.”

Cushing-murray quickly gave up his idea of being a “rabbit.” Thanks to a second wind late in his career, he’s now a greyhound.

The Shortstop

When describing UCLA shortstop Nicole Odom, one is tempted to let the numbers do the talking:

* At age 17, youngest softball player at the 1993 U.S. Olympic festival, an American tournament for world-grade athletes.

* Fastest recorded hand speed--a measure of infielding prowess--at the 1994 U.S. Olympic festival.

* Batted over .300 in her first year of major college softball.

* Started all 57 games last year as a freshman.

* Batting over .400 this year for the second-ranked Bruins.

But statistics are only part of the story.

Tall, charismatic and graceful, the 19-year-old with the rocket arm and wicked bat possesses the savvy and confidence of someone much older. If Chris Evert grew up in Torrance wearing cleats instead of sneakers, she would have been Nicole Odom.

“I’ve been coaching for 16 years, and having a player like Nicole makes you love your job,” said UCLA co-head coach Sue Enquist. “She’s inspiring because she’s not only a great athlete, she’s a team player, a player’s player.”

A coach’s dream. An opponent’s nightmare.

“Odie,” as she’s known on the team, carries a big stick but speaks softly. On a squad dominated by All-American seniors such as outfielder Kathi Evans and third-base player Jennifer Brundage, it could be no other way. Still, Odom is quietly emerging as the team’s next great leader.

Last year, the Bruins went to the College World Series and finished fourth in the nation. This year, the team opened with 15 straight wins and is one of the favorites to capture the college crown, which will be determined May 23-29 in Oklahoma City.

“I’m here to win a national championship,” Odom said after a recent practice at Easton Stadium on the UCLA campus. “But after college, my goal is to win on the Olympic team.”

Since this is the first year women’s softball has been accepted as an Olympics sport, the Torrance teen-ager will be competing for a spot on the squad against older, more experienced, semipro softball stars who have been waiting years for their turn on the Olympics stage.

But Odom specializes in beating the odds. Once the youngest softball player at the Olympic festival, she is expected to be invited to the Olympic tryouts in September. Fifteen players will make the team.

“If she continues to progress like she is, she’s definitely one of the players in contention for the year 2000 and possibly 1996,” Enquist said. “It comes down to her ability to execute in the pressure situations in the tryout camp.”

Odom knows the challenges. She’s faced the best players in the country during the past two festivals. “It was an honor for me to be playing alongside these big names,” she said. “Just for me to be out there with them, and knowing I could play up to their caliber, meant a lot to me.”

Freeze this quote. In a few years, that’s what other athletes will be saying about Odom.

The Spiker

Those who have followed Randy Stoklos’ phenomenal career may think he needs another victory like O. J. Simpson needs another lawyer.

The two-man beach volleyball legend has won 116 tournaments and earned more than $1.3 million on the pro tour. But there is one title that has eluded the gentle giant from Pacific Palisades: Olympic gold. And at his age, he may be stretching his 6-foot-4 frame to the max.

In 1980, when he was playing six-man volleyball for UCLA, Stoklos tried out for the American team and was the last man cut. Two years later, while training for the 1984 games, he dropped out. “I opted to work for the family (loudspeaker) business, for my family to get ahead in life, rather than for me to be in the Olympics,” he said.

In the mid--1980s, Stoklos and his partner at the time, Sinjin Smith, hit the beach. They caught the perfect wave, peaking just as the sport crested from a regional string of low-paying California tournaments into a multimillion-dollar, nationally televised sport.

Back then, Stoklos would have been a lock for the American team, except for one problem: two--man volleyball was not an Olympic sport. Like women’s softball, two-man beach volleyball makes its debut in the 1996 games.

Another problem for Stoklos: he turns 35 this year. Many of the top players are in their 20s. “It’s definitely stretching it,” Stoklos said. “I’m working out with a trainer for the first time in my life. I never needed it before. I was No. 1 for 10 years. There are younger players out there now. I’ve got to be in better shape.”

Besides adding more muscle, Stoklos took on a new partner in 1993, Adam Johnson of Laguna Beach. The Stoklos-Johnson team was ranked No. 3 by the Assn. of Volleyball Professionals last year.

Kent Steffes of Santa Monica and Karch Kiraly of San Clemente were No. 1, followed by the team of Mike Dodd of El Segundo and Mike Whitmarsh of San Diego. Three teams will represent the United States.

Under a complicated system still under debate, the top team will qualify by earning points on the international volleyball tour, not the lucrative tour run by the volleyball pros. That means Stoklos and the other pros could forfeit thousands of dollars--maybe more--to pursue their Olympic dreams.

Two more teams will be chosen during a qualifying tournament scheduled for June, 1996.

“We’ll lose money,” Stoklos said. “It costs a great deal to travel internationally and there’s less prize money.”

But money is only one issue. “When I first started playing volleyball, I played it for the love of the game,” Stoklos said. “I never thought I would become a star and make a living at it.”

Now that he’s comfortable financially, Stoklos can’t sit still. “I’ve won everything I’ve had to win in beach volleyball,” he said. “My goal for the past year has been to win the Olympics. I think Adam Johnson and I are the team that can win the gold medal.”

More to Read

Go beyond the scoreboard

Get the latest on L.A.'s teams in the daily Sports Report newsletter.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.