Growing Flock of Catholics Take Many Paths in Africa : Religion: On coming visit, Pope will find growing restlessness to tie local customs to church traditions.

- Share via

NAIROBI, Kenya — Each Sunday, Africa’s Catholics tread paths along rough roads, through mud and dust and heat in their best clothes, to fill the day with exuberant songs of worship.

Sometimes, though, they tread more ominous paths. Just a year ago, hundreds of thousands of African Catholics were butchered--mostly by other Roman Catholics--and the walls of their churches remain stained with blood today.

Some African Catholics deliver the milk of kindness to the infernal reaches. They die of the virulent Ebola virus while trying to help the sick in a Zairian hospital, duck artillery to bring relief to the south of Sudan, swelter in West African heat to educate the young--and they share, no matter how heavy their burden, the satisfaction of universal faith.

But some African Catholics cozy up to tyrants. They defend a failing status quo while AIDS and overcrowding compound Africa’s misery. And too, some are apt to surprise you when they say things like: “I am a good Catholic. And so are all three of my wives.”

The flock of 128 million African Catholics is the fruit of a century-long campaign to proselytize sub-Saharan Africa. It is the “most successful missionary effort in history,” says U.S. scholar Thomas J. Reese of the Woodstock Theological Center.

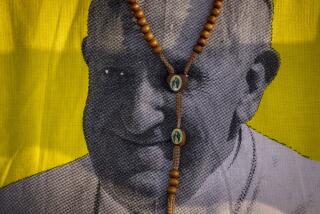

And now, for the 11th time, the flock here awaits Pope John Paul II.

But not for an ordinary visit.

The pontiff will arrive in Africa on Thursday for a one-week, three-nation pastoral tour. And, at last, he promises to address Africa’s growing restlessness: How much of African culture should be permitted into Africa’s now-mighty Roman Catholic Church?

Not a simple matter. Daily customs and beliefs of many Africans fly in the face of Rome’s traditions. Some of them are harmless, but others are surely intolerable to the Vatican.

Even as Catholicism has grown here, its devotional roots remain shallow. Rosary in the morning, witchcraft in the afternoon, as is sometimes said.

So, for the past four years, Rome has pondered how much to give.

Religious fervor is great in Africa; religious loyalty often is not. The continent’s 703 million people represent the world’s most bountiful holy free-for-all.

Christian missionaries probed beyond North Africa 400 years ago. But their great success occurred during the second half of this century, coinciding with Africa’s burst in population. African Catholics almost doubled in number from the mid-1950s to 1970, and they grew 60% more by 1980.

Then came the “lost decade” for the continent, when poverty worsened, when trust in other institutions sagged--and when faith was one of the few choices an African really had.

By 1995, church membership had grown an additional 270%.

The trick to these numbers, though, is underwritten by Africa’s expanding multitudes: The Catholic share of the population actually only increased from 9% to 18% in the past generation. But the pie had grown huge.

Not that today will foretell tomorrow. In its history, Africa has seen abrupt shifts in religious allegiance. Countries along the northern rim of the continent were vibrantly Christian until the 8th Century, when Islam swept the region.

Today, in the sub-Saharan nations, established Western denominations are increasingly contested by a new surge of Islam and by an explosion in home-grown independent African churches in which traditional culture is glorified, not shamed.

On any given Sunday in big African cities, indigenous churches can be seen sprouting. They may have no roofs; they may have no land. They may hold services in vacant lots and even on grassy patches of highway traffic circles.

But they have followers, singing and reaching to the sky. Among them are young disenchanted Africans who shout out their gospel: The developed northern countries have failed the impoverished peoples of the south.

“The question for this visit is whether the Pope will give us a plan of action, the liberty to experiment . . . whether Africanization, or enculturation, of the church will proceed, or whether every little thing will still have to go through Rome,” says Father Bill Knipe, a Maryknoll priest in Nairobi. “Right now, there is a flourishing of African independent religions, Africans forming their own churches. And they are constantly bleeding members from established churches.”

Many experts believe the challenge facing the Pope in Africanizing the church is nothing short of historic. “If this chance is not taken, there may not be another,” the National Catholic Reporter concluded in an analysis.

The urgency can also be seen in the changing demographics of Catholicism.

“There is a very good chance that, by the year 2010, the Catholic Church will be a Third World church with the majority of its adherents from Third World countries,” says Eric Hanson, a professor at the University of Santa Clara in the Bay Area and author of “The Catholic Church in World Politics.”

A generation ago, Africans made up 5% of the world’s Catholic faithful. Today, they make up more than 12% and outnumber North America’s Catholics by 30 million. A good measure of this rapid growth occurred because of the similarities, not differences, between indigenous culture and Catholicism: a shared emphasis on family, belief in supernatural power, acceptance of authoritarian leadership.

Only recently have Africans and church leaders in Rome begun to dwell on their differences.

Marriage is most often used to illustrate the tensions between the church and African culture.

Many Africans regard marriage not as an event involving vows and consummation, as in the West, but more as a process that includes family and clan. Sometimes, marriage is complete only when the bride becomes pregnant. And a great number of Africans continue to practice traditional polygamy.

African culture also departs from Western orthodoxy in countless other ways, big and small--in music, health care and sexual mores, to name just a few.

Critics are sometimes drawn to say that, in fact, the Catholic Church is in tune with African culture in areas where indigenous tradition is most vulnerable to criticism: the subservient role delegated to women in African society, for instance.

“The practice of women’s circumcision . . . treatment of widows in traditional settings, the place of girls in the family and other practices that make women second-rate citizens have not been fully addressed by the church,” says Kathryn Hauwa Hoomkwap, a Nigerian activist.

And the familiar argument over contraception bears down with extra weight on a continent that cannot feed itself and where an estimated two-thirds of those infected with the human immunodeficiency virus, or HIV, which causes AIDS, live and die.

In Kenya, for example, where the Pope is scheduled to make his final stop on this journey, the government recently congratulated itself on 3% economic growth--without emphasizing that population growth was 3.4% in the same year, meaning that the country grows poorer even in good times. Meanwhile, church leaders are pictured on the front page of Nairobi newspapers burning sex education materials.

The Pope’s trip is intended to celebrate and conclude a synod of 300 African bishops held in Rome last year. The monthlong convention and subsequent debate itself were the result of pent-up demands by African Catholics for a freer hand in dispensing the faith. “Perhaps they have values that we Westerners have lost,” the pontiff said about Africans in his last visit here.

Yes, but will room be made for these values in church rituals and practices? During the buildup for this papal trip, some here expressed doubt. For one thing, the Africa synod was held in Rome, not Africa. For another, Rome prepared the written agenda, which was widely criticized.

“Where in this document are the great, unfolding processes of democratization, the dramas of civil wars and refugees, the anguish of the AIDS victims, the questioning gaze of the malnourished children, the enormous positive energy of our youth, the awakening giant that is the African woman? Where is Africa?” Nairobi priest Renato K. Sesana asked in an open letter to the Vatican. The letter continued:

“If the church will not be with us as an understanding and loving mother, to whom will we turn? To the African independent churches? To the new American sects from the Bible Belt? To Islam?”

But there is another side to the culture argument. Only a year ago, too free a hand and not enough resistance to destructive fanaticism plunged the church into the shame of Rwanda.

At the beginning of 1994, Rwanda was the most Catholic country in Africa, with a claimed church membership of 80% of the population. Rwanda’s bishops were thought to be among that nation’s most influential people. By summer, however, the tiny nation was a rotting, desecrated graveyard that few sane Catholics could fathom.

During these catastrophic weeks, Rwandans hacked, shot and kicked to death 500,000 other Rwandans, or perhaps many more--Hutus killing Tutsis, extremists killing moderates, parishioners killing priests, priests killing parishioners. More people died in churches and parishes than anywhere else, according to Africa Rights, an independent human rights group.

For Catholics and others, what remains so unsettling about the Rwandan genocide is how the culture of ethnic rivalry, fear and hatred so easily and swiftly overcame the professed Christian beliefs of so many Rwandans.

“Christianity is not rooted in the African mind--that’s a Western myth,” says Joseph Ngala, an East African journalist who covered events in Rwanda for a Catholic publication.

“If it was rooted, Rwanda would not have happened. You had priests calling people to the church to be massacred, sisters joining in the massacres, people who went to the same church, who grew up in the same schools, killing each other. Something was awfully wrong.”

Perhaps just as numbing to ponder is the widely spread accusation that Rwanda’s senior clerics share the guilt, both for their action and inaction.

In a 740-page report on the killings, Africa Rights concluded that many priests and nuns struggled to save people but were “undermined” by superiors who were “giving spiritual support to the extremists before and after they launched their apocalypse. . . . The church pulpits provided the opportunity for reaching almost the whole population with a strong moral message that could have played an instrumental role in halting the genocide. But they stayed silent.”

Although different in degree, a comfortable accommodation between church and government permits tolerance of injustice in other countries on the continent, according to Catholic social activists and even some conservatives.

As a critic in the Kenyan diocese complains privately, too many of Africa’s Catholic leaders “want to share the power with the regimes. . . . Have you seen the kind of palatial houses some of these bishops live in? . . . And yet our hospitals cannot pay customs duty on medicines.”

Beyond the search for blame and villains, the question remains: What is that formula of leadership and freedom, of governance and spirituality, of helping hands and self-reliance, that can halt the descent into greater suffering?

Father Patrick D. Gaffney, a University of Notre Dame anthropology professor, describes today’s African Catholics as a generation “in transition, or crisis. In terms of numbers, it’s growing, but in a confused and random way. Better to say it’s growing in a number of dimensions.”

It is to this Africa that Pope John Paul II comes, seeking to keep his church ordered and still vital.

Times researcher Doug Conner contributed to this report.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.