Defunct N.M. Site Starred in Cosmic Ray Research From ’58 to ’72 : Physics: Scientists hope to revive Volcano Ranch architecture and add latest technology for two new facilities in quest to understand universe.

- Share via

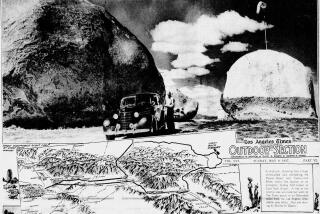

ALBUQUERQUE, N.M. — Wind whistles through a tree’s twisted skeleton--a sentinel over a patch of desert where pieces of concrete, wire and clear yellow thermoplastic tell a tale of cosmic ray research.

A nearby bundle of wire juts above the ground, frayed ends once connecting a scattered array of detectors to amplifiers and oscilloscopes in an adobe building on a mesa west of Albuquerque.

The building is gone. But crumbled cinder-block walls of an outbuilding remain among the sand and scrub vegetation slowly reclaiming the vestiges of man--including chunks of mangled, rusted metal left on this World War II-era bombing test range.

The Massachusetts Institute of Technology’s Volcano Ranch cosmic ray research station, in business from 1958 to 1972, was cutting edge for its time.

“Volcano Ranch was one of the earliest large cosmic ray air shower detector systems,” said Michael Wolfe, a research assistant who worked at the site for 11 years and is now an audio specialist in Seattle.

Gene Loh, a University of Utah physicist, said the testing at Volcano Ranch “proved that we can look at the cosmic ray showers before they hit the ground. We can look at individual showers as they progress down the atmosphere.”

Now, scientists want to resurrect its basic architecture, coupled with the latest technology, in a pair of grand research sites proposed for the Northern and Southern hemispheres.

Rene Ong, an assistant professor of physics at the University of Chicago, said Volcano Ranch’s “tradition that started some 30 years ago will be continued in a wonderful way” with the proposed Pierre Auger Cosmic Ray Observatory.

The Holy Grail of cosmic ray research is eventually understanding the birth and evolution of the universe. But for now, researchers would like to know where the rays come from, their makeup and their energies.

“We have some answers, but we don’t have the answers to the level we’d like,” Ong said.

Cosmic rays are charged particles from outer space, mostly atomic nuclei, or protons, but ranging up to heavier nuclei such as iron.

Iron “is an important end product of stellar evolution,” Loh said.

The particles, traveling at nearly the speed of light, have as much as 100 million times more energy than the particles produced in the most powerful earthbound particle accelerator at Fermilab in Batavia, Ill.

“Somewhere in our galaxy, there’s an accelerator that is producing these particles that are basically nuclei that have all their electrons stripped and ejected. The accelerator could be an exploding star, a black hole, a neutron star,” Ong said.

When a cosmic ray hits molecules on top of the Earth’s atmosphere, it creates a shower of atomic particles, like a cue ball hitting a rack of billiard balls.

“A nuclei coming in from outer space--a big iron nuclei, for example--would never survive to the ground. The atmosphere shields us,” Ong said.

The iron nuclei will “break up into smaller pieces, basically to fundamental particles--electrons, protons--and these things propagate down to the ground as remnant particles . . . mostly electrons,” he said.

Ground-based detectors scan the skies for the cascade of particles moving at nearly the speed of light--the bigger the shower, the bigger the nuclei.

Volcano Ranch, billed by MIT in the late 1950s as “the largest cosmic ray shower experiment ever attempted,” initially cost $134,000 to build. It had 19 cosmic ray detector sites, some as far as two miles apart.

“Nothing quite on the scale of this . . . had ever been constructed,” said Derek Swinson, a physics professor at the University of New Mexico.

The project was conceived by Bruno Rossi, an MIT physics professor who played a leading role in the study of cosmic rays and the development of space physics before he died in 1993 at age 88.

“I was given the assignment of leading this work in New Mexico, so it was my baby from that point,” said John Linsley of Albuquerque, a physicist who led the research and later worked at the University of New Mexico.

“However, it was always under the fatherly guidance of Rossi. He was a mentor to me.”

Volcano Ranch’s location near Albuquerque--a big city with a university--was an advantage, Linsley said.

“It was flat land, so it was relatively easy for our work on a large scale, and it was at a convenient elevation more than a mile above sea level,” he said.

In 1961, Volcano Ranch picked up a massive shower of remnant particles from a cosmic ray with a power of 100 billion billion electron volts, Linsley said.

“It was 50 times the energy of any previous cosmic ray detected, and it held the record for many years,” he said.

An electron volt is the amount of energy an electron gains when accelerated by a potential of one volt. Electrons in a television set are accelerated by a picture tube to an energy of about 50,000 electron volts.

The last important research to come out of Volcano Ranch occurred in 1972, when a new type of detector was tested for the Fly’s Eye cosmic ray research site at Dugway Proving Ground, 75 miles southwest of Salt Lake City, Linsley said.

Fly’s Eye, which scans the skies only at night for the faint glow caused by particle collisions, broke Volcano Ranch’s record for cosmic ray power. On Oct. 15, 1991, it detected a hit of 300 billion billion electron volts.