Revolutionary Revelations and That’s No Lie

- Share via

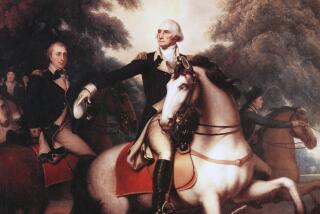

In words befitting George Washington’s birthday today, Jack D. Warren cannot tell a lie.

So, being the Honest Abe that he is, Warren, a Washington expert at the University of Virginia’s The Papers of George Washington project, is ‘fessing up about the most famous line uttered 250 years ago by George himself: “I cannot tell a lie.”

Never happened.

Warren, 33, an assistant editor for The Papers project, knows just about everything regarding Washington; the project has published 31 volumes of Washington documents and an additional 54 are planned. “Washington is kind of a mythic figure, but the real Washington,” Warren says, “is just as fully interesting as the myths about him.”

And, by George, Warren is out to bust a few myths, sleuth the truth and fill in folks on things we never knew about the Big Daddy of our nation.

So, if you’re ready to gorge on George, read on. But first, dig out the gent on the greenback and have it handy as a visual aid. (Hint: It’ll be something you can sink your teeth into--wooden, you know.) Now, to the skinny:

* George was a tightwad. You know the story about him flinging a silver dollar across the Rappahannock River? Not. Washington was never one to throw away money. In fact, he often whined about low wages throughout his military career, saying he served “for the shadow of pay.”

* Washington was stern and forbidding, known for sometimes being a pain in the neck. His legendary temper led to Alexander Hamilton resigning as Washington’s most trusted military aide because Hamilton was chided by his boss for being 10 minutes late for a meeting.

* The father of the father of our country was Augustine Washington, a tobacco planter who “was a man on the make, looking to get ahead with real estate deals,” Warren says.

* George’s mother, Mary Ball Washington, was widowed when George was 11. She never remarried and as a single-parent mom raised five kids on her own--something uncommon during that era. Mary, who died in 1789 of breast cancer--the year her son became president--was known for being a “stubborn, complaining, determined, tough old mother.” Says Warren: “George couldn’t do enough to please Mary as far as Mary was concerned. There was not a great deal of love lost” between the two.

* Washington never chopped down his father’s cherry tree.

* Washington never prayed on his knees in the snow at Valley Forge, one of several stories fabricated by Mason Locke Weems, a contemporary and biographer of Washington’s who fibbed about George to inspire young people.

* He had few friends. “Washington didn’t know Jefferson very well,” Warren says. “Washington and Adams, his vice president, had no contact at all during the Revolution. Washington’s personal friends were mostly people in the neighborhood in Northern Virginia where he lived.”

* James Craik, Washington’s personal physician, was George’s best friend. The two served in the French and Indian War and were constant companions during the Revolution. Craik named one of his sons George Washington Craik.

* The Marquis de Lafayette (born Marie Joseph Paul Yves Roch Gilbert du Motier), a French nobleman who served in the Continental Army in the Revolution, “became like a son to Washington” and once smuggled a Spanish jackass--as a gift for George--out of Spain. Unfortunately, the ship sank before it reached the Colonies. (Lafayette later named his son George Washington Lafayette.)

* Washington was “the strong, silent type,” Warren says. “He wasn’t a talker because he was self-conscious about not being particularly well educated. He couldn’t read French or Spanish. He went nowhere, college-wise”--unlike Jefferson, who attended William and Mary; John Adams, Harvard; and James Madison, Princeton.

* Washington was a towering hunk of a man at 6 feet, 2 inches at a time when the average height for a man was 5 feet, 4 inches.

* He was a graceful dancer, an important attribute for a gentleman.

* In spite of his big nose and a face scarred from smallpox, Washington was considered quite attractive and even caught the eye of Abigail Adams upon noticing him for the first time in 1775 when George was a delegate to the Continental Congress. “It was definitely his carriage,” Warren says about Washington’s appeal. “He occupied his height. When he walked into a room, he didn’t have to say ‘I’m here.’ He arrived.”

* Most people referred to him as “The General.”

* In letters, he referred to his wife, Martha, as “Patcy.”

* Martha burned all of George’s letters, a fairly common thing for the wives of public men to do, which “doesn’t mean Martha was covering up any kind of scandal,” Warren says. Besides, Washington “was much too conscious of his reputation.”

* But as a young man in his 20s--and before his marriage to Martha--George “developed a strong attachment to his then best friend’s wife, Sally Fairfax.” George wrote her an affectionate letter, but the relationship “didn’t go anywhere. He sort of pined after her. Some writers have tried to make a torrid affair and there is no evidence of this,” Warren says, adding that Fairfax, her husband and George remained a close threesome.

* “Young men were always attracted to Washington,” Warren says, “partly because he was physically strong, athletic and enjoyed outdoor sports.” Among his male aides and secretaries was Hamilton, “who loved and admired qualities in Washington like his personality and character.”

* Washington had a real fondness for children, “a sad thing for him because he never had any of his own,” Warren says. “At 18 he had smallpox and that could have rendered him sterile.” George helped rear his stepdaughter, Martha Parke Custis, who, as a teenager, died of epilepsy. He also adopted two of his step-grandchildren.

* Washington set up a fund to take care of infirm and aged slaves that worked on his Mount Vernon plantation “so they wouldn’t be impoverished” after they were set free, Warren says. “People were still drawing money out of that endowed fund 40 years after Washington’s death”--at age 67 from symptoms that suggested pneumonia. “High fever and virtual suffocation did him in,” Warren says.

* Math was his favorite subject; he was adept at trigonometry.

* Washington was born on Feb. 11 but decided to celebrate his 20th birthday 11 days later on Feb. 22 when the first leap year in 1752 was observed. “It was determined that the calendar was 11 days behind so Washington, who respected scientists--and agreed with them that the calendar was out of whack--added 11 days to his birthday,” Warren says.

* Washington’s passion in private life was making Mount Vernon a great model farm for America. “He was the kind of guy who took his first paycheck as a down payment on a piece of real estate,” Warren says.

* Washington is principally responsible for bringing the mule--the offspring of a jackass and a mare--to American agriculture. For 15 years he tried to get his hands on a Spanish jackass for a breeding program at his farm. (Remember Lafayette’s attempt?) Finally in 1785 he acquired the jackass as a royal gift from King Charles of Spain.

* Washington’s grocery list always included tooth powders.

* Got that dollar bill? Look at Washington’s mug. His lips are pursed and he’s clenching his jaw, Warren says, because George is biting on metal springs that are pushing back. Sure, we all know he had false teeth. Wooden ones, right? Wrong. Washington wore dentures made of hippopotamus ivory and one constructed from his own pearly whites. By the time he was president, he only had one tooth left in his head. In 1999, on the 200th anniversary of Washington’s death, the Mount Vernon Ladies Assn.--which maintains Washington’s home--may display George’s false teeth.

And that’s the tooth.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.