Bomb Suspect, Brother Saw Paths Diverge

- Share via

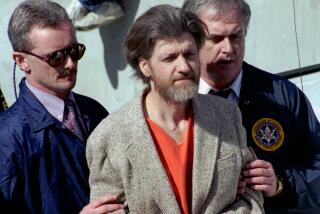

SCHENECTADY, N.Y. — Among the mysteries that enshroud the Unabomber investigation, perhaps none is as intriguing as the tale of the brothers Kaczynski: Theodore, the Montana hermit who authorities believe is responsible for the longest string of bombings in U.S. history, and David, the gentle social worker who may have cracked the case.

The similarities are difficult to ignore. Both are shy and extremely intelligent. Both have a philosophical bent. Both spent time in wilderness, living in remote cabins without running water or electricity. Both have immersed themselves in literature and writing.

Yet somewhere along the way--no one can yet pinpoint when--the brothers chose divergent paths, channeling their shared characteristics in markedly different ways.

Ted cut himself off from civilization, abandoning a budding career as a mathematics professor at UC Berkeley to cloister himself in the stunning wilderness of Montana’s Blackfoot River Valley. There--if the FBI is correct in its suspicions that he is the Unabomber--he employed his mathematical genius in a twisted, lonely effort to cure what he saw as society’s ills by killing people.

David experimented with isolation as well but left the remoteness of his Texas cabin six years ago to marry a popular and outgoing philosophy professor in this aging industrial city in upstate New York. He shoots hoops with his neighbor’s son and plays in a softball league. But he and his wife still retreat to his property in Big Bend from time to time, seeking what their friend and neighbor, Mary Ann Welch, describes as “personal and private rejuvenation.”

Instead of contemplating society’s troubles from afar, David Kaczynski plunged in. He works as assistant director of an emergency shelter for runaway and homeless teens, a job to which friends say his knack for patient listening makes him well-suited. He has spoken eloquently on local television of children living in cardboard boxes and rummaging through trash in search of meals. People here are not surprised that, when he began to suspect his brother was the Unabomber, he turned him in.

“It’s almost as if in that family, they had all these wonderful traits,” says a friend of David Kaczynski’s, requesting anonymity. “They came out in such a way with [David] as to build kindness and compassion, and his brother somehow flipped over.”

Experts say it is not at all surprising that the brothers share some traits; increasingly, medical research is finding strong genetic components to personality. Shyness, for instance, is one characteristic that is widely believed to be inherited.

Thus the story of the Kaczynski brothers as told by friends and colleagues may be a classic case of nature vs. nurture, says Reid Meloy, a UC San Diego forensic psychologist who has tracked the Unabomber case closely. If Ted Kaczynski does indeed turn out to be the Unabomber, Meloy says, the best clues to his mind-set will be found in the years from 1969 through 1978, after he dropped out of society to move to Montana and before the first bomb exploded.

It was during those years, Meloy theorizes, that the brothers set out upon their distinctly different paths through life.

“It’s real interesting to me that one brother experimented with isolation and then went back to attach and bond and join society, and the other brother continued in that direction, becoming more and more isolative,” he said. “That’s the key that will unlock it.”

The photograph is like so many pictures clipped from family albums; two shirtless boys sitting in a backyard sandbox with their neighbors. The 1954 picture of David and Theodore Kaczynski--David sucking the last bit of ice cream off a wooden stick, Ted staring languidly at the camera--is a middle-class tableau, striking in its ordinariness. It bears no hint of the men they would become.

Their childhood was spent in Evergreen Park, Ill., a working-class suburb that until last week staked its claim to fame on being the site of the nation’s first shopping mall, Evergreen Plaza, built in 1952. The Kaczynskis lived in a three-bedroom brick Colonial on a tree-lined street near Duffy Park.

Ted was born on May 22, 1942; David was born eight years later. Their mother, Wanda Kaczynski, was intent upon educating her two sons, reading to them from scientific magazines, carting them off to the Museum of Science and Industry and the Adler Planetarium on Sundays.

Her husband, Theodore R. Kaczynski, worked at a sausage factory in the “back of the yards” neighborhood, an ethnic Polish enclave, neighbors recall. He taught his boys to love the land. When they were young, he took them on weeklong trips into the woods, where they lived off whatever they could gather. Once they ate a porcupine.

The Kaczynskis were a socially conscious, politically astute couple. They were liberal Democrats, and they were vocal about it, writing letters to the editor of the Chicago Tribune. The father is said to have despised Richard Nixon.

Their children excelled academically, and this, friends and neighbors say, was Wanda Kaczynski’s greatest pride. Ted skipped a grade or two. Bill Widlacki, a former classmate, recalls him as “beyond smart, a genius, bordered on Einstein levels. . . . He was a 15-year-old going to school with kids who were 17, 18 years old. . . .

“He was a nice kid, polite, courteous, easygoing,” Widlacki adds. “But he was out of place. Like with girls. I never saw him dating anybody in school. . . . He didn’t have close friends.”

Seven years is a large gap between children, and so the brothers came of age at different times. When Ted went off to Harvard University at age 16, his brother was still in elementary school.

David shared his brother’s love of books, those who know him say, and while shy, he was not nearly so withdrawn. He liked baseball and basketball and had a high school sweetheart, Linda Patrik, the woman who eventually became his wife. (In a curious twist, Patrik obtained her doctorate from Northwestern University on June 17, 1978, less than a month after the Unabomber’s first bomb exploded on that campus.)

Like his brother, David attended an Ivy League school, Columbia University. He graduated in 1970 with a bachelor’s degree in English. By this time, Ted had already obtained a doctorate in mathematics and had taught at UC Berkeley, a job he had abruptly abandoned in 1969.

In 1971, the Kaczynski brothers bought property together on Stemple Pass, in the Montana mountains near the Continental Divide. It was on this land that Ted Kaczynski built the simple 10-by-12-foot shack from which, the FBI suspects, he ran a homemade bomb factory and terrorized the nation for 17 years.

While Ted carved out a new life for himself in Montana, his brother became a high school English teacher in the Iowa town of Lisbon, a hamlet of 1,500 where his parents had lived for a time. “Dave was so well-read,” recalls fellow teacher Bob Bunting. “No matter what you talked about, history or authors or anything, he knew something about it.”

He spoke little of his older brother. “All he ever said about Ted was just how smart he was,” Bunting says. “I knew he had taught at Berkeley and had that cabin in Montana.”

In the mid-1970s, friends say, David Kaczynski quit his job in Lisbon. His dream was to be a writer; he had been working on a book “of his views on life,” according to another fellow teacher, Ron McDermott. McDermott says his former colleague went back to Chicago and drove a bus for a time, saved up his money and then went off to write.

At some point, David Kaczynski built his own cabin in West Texas, in or near Big Bend National Park. He lived there for a time, falling in love with the Southwest. It is that setting that provides the backdrop for much of his writing. “He loves his place down in Texas. He loves the desert lands,” says Welch, his next-door neighbor in Schenectady.

If he had his druthers, David Kaczynski would make his living as a writer. He has published several poems and short stories, Welch says, that are rich in description and detail. The one she read was so layered and replete with literary allusions, Welch says, she had to reread it several times to capture its fullness.

In 1990, after corresponding for several years with Patrik, he joined her in her Schenectady home, a pretty green-and-white clapboard bungalow not far from a trendy commercial strip. They were married in a quiet backyard ceremony conducted jointly by a minister and a Buddhist monk. Brother Ted did not attend.

Unable to support himself through his writing, David Kaczynski took a job working in a group home for developmentally disabled adults and later joined Equinox, a well-respected private nonprofit social service agency in nearby Albany. Friends say he was perfect for the job.

“Dave is a very good listener,” Welch says. “He’s a reflective person. He won’t bombard you with words.”

What, if any, contact he had with his brother in recent years remains unclear. Welch says that David spoke little of Ted. But, she adds, Wanda Kaczynski--who would come to Schenectady from Illinois to visit her younger son--spoke occasionally of him, expressing a mother’s concern that her older child could get hurt living out there in the wilderness all alone without friends or family.

Ted, who had no phone, wrote an occasional letter to his mother, although she wrote more often than he. Several years ago, she visited him in Montana, choosing to stay in a motel rather than his tiny cabin. Sources close to the case also have said Wanda Kaczynski sent her son substantial sums of money and has turned over canceled checks to the FBI.

“She wished that he might have made different choices,” Welch says, “maybe not living in such isolation so that she would have more of an opportunity to visit with him. But she accepted his lifestyle.”

Whether she saw the cabin, which federal authorities say was filled with materials that could be used to make bombs, no one seems to know. Other questions remain as well. Did David ever visit? How must David have felt, when, upon cleaning out his mother’s house in Lombard, Ill., he stumbled across old papers of Ted’s that seemed strikingly like the 35,000-word Unabomber manifesto published in newspapers last year?

The men who could provide the answers are not talking.

Ted is under a suicide watch in a Montana jail. David has been forced into a jail of his own; since it became known that he had turned over the papers leading to his brother’s arrest, he and his wife, along with his mother, have been trapped inside their house by a phalanx of TV cameramen and reporters awaiting a glimpse or a comment they do not wish to give. On Saturday, their attorney emerged to say he would hold a press conference Monday in Washington.

Meanwhile, the town of Schenectady is rallying round its newly famous citizen to protect the privacy he so cherishes. Editors of the student newspaper at Union College, where Patrik teaches, say they voted not to help the national press. Neighbors have distributed fliers saying, “Leave them alone.” The staff at Equinox have been issuing “no comments” all week.

“I see this almost as a morality play,” says Welch. “These people came to a traumatic decision, but within that whole story is the feeling that they were considering the rights of society above their own rights to deep-six a family secret. . . . Look at the sacrifice they made. And how ironic to see their personal rights to remain in their own home and to remain silent be trampled on.”

Times staff writer Judy Pasternak in Chicago contributed to this story.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.