The Fight Against Crime: Notes From The Front : Super Sleuths Uncover Clues in the Writing

- Share via

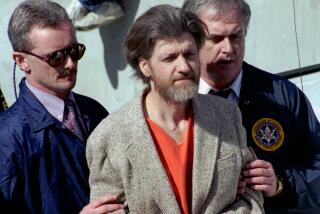

When federal agents raided Theodore J. Kaczynski’s remote Montana cabin last month, most people naturally wanted to know if the suspected Unabomber kept any bombs in there. Not Karen Chiaroty.

“The first thing I was wondering was if they found any typewriters,” said the officer in charge of the LAPD’s Questioned Document Unit, which evaluates all manner of notes, checks, letters, records and contracts for authorship and authenticity.

To Chiaroty and her fellow document examiners in the district attorney’s office, the Sheriff’s Department and the private sector, the Unabomber case is something like professional nirvana. Like criminal minds, old typewriters carry individual defects--broken letters, odd spacing, model-specific type faces and other quirks that make them traceable to a particular machine.

Not only did the Feds find three manual typewriters in Kaczyski’s cabin, but also a master copy of the 35,000-word manifesto that the Unabomber sent to two newspapers. Usually, examiners consider themselves lucky if they have a single typewritten page to work with.

“Everybody in this field was very interested . . . because in terms of dealing with the evidence, manual typewriters are a lot better to work with because they have more in the way of unique defects,” said Howard Rile, a veteran examiner with Harris and Harris, a private Los Angeles document-examining firm.

The treasure trove of typewriter evidence, however, is also a reminder that this valuable tool is being lost in the computer age. Truth be told, document examiners don’t see a lot of “typewriter cases” anymore--and even fewer involving manual typewriters.

Bruce Greenwood, a forensic document examiner in the district attorney’s office, said he handles only about two manual typewriter cases a year now. Typewriter evidence helped nail a Glendale child pornographer, he recalled--but that was nine years ago.

Electric typewriters still provide clues, even though document examiners worried that the machines would doom their profession when they became common in the 1960s, Rile said. Since most use replaceable daisy wheel or golf-ball type, it was feared they would not be in use long enough to develop the unique defects that manual machines do after years of use.

As it turned out, though, the electrics had an advantage: Examiners quickly realized they could read the single-pass ribbons to determine that a document had in fact been typed on a specific machine.

But computers--or more specifically computer printers--have brought new challenges, Rile said. Many manufacturers of printers use the same type style, making documents harder to trace. And because dozens of computer users may be hooked up to the same printer in an office, finding the author is more difficult as well.

Yet Peter Tytell, a New York documents examiner who is one of the nation’s foremost experts on typewriter cases, said he is confident that his profession will figure out how to read the clues, however limited, that computer printers leave behind. Laser printers “can also develop unusual characteristics in the paper path, with the fuser assembly” that will leave unusual stripes and indentations on paper, he pointed out.

“Many people, for the last 100 years or more, have thought they could hide their identity by using a typewriter and they were wrong,” Tytell said. “Similarly, we feel that modern technology is faceless, but it’s not.”

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.