Skipper in Cruelty Case Now Fugitive on High Seas

- Share via

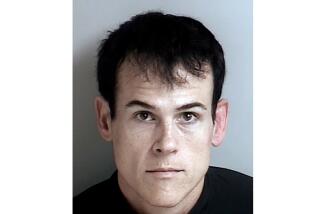

As if the case of Bruce Mounier wasn’t already chock-full of maritime melodrama, the allegedly tyrannical and abusive fishing captain is now considered a fugitive on the high seas, reportedly island-hopping as he eludes federal authorities.

The 55-year-old Mounier, indicted last year under a rarely invoked, 160-year-old statute forbidding cruelty at sea, has yet to answer to charges that he starved and otherwise mistreated four crewmen, including a Valley Village resident, aboard the Magic Dragon.

“He’s not within a jurisdiction where I can arrest him,” Assistant U.S. Atty. Mary Andrues said. “We consider him a fugitive.”

Mounier’s attorney, Carleton Russell--who has spoken to his client only once since the September indictment in U.S. District Court in Los Angeles--said Mounier is simply “trying to feed a family and survive.”

A lifelong deep-sea fisherman who has pioneered nautical techniques, Mounier is doing what he does best--trolling tropical waters for fish, according to Russell, who said he talked to Mounier about three weeks ago by phone from the South Pacific.

Russell, a civil attorney, is defending Mounier against a $20-million lawsuit filed by crew members in the case that led to the federal indictment. He says Mounier has no criminal defense attorney, but he expects him to return to the United States.

“He’s not going to go to Pitcairn Island and hide out,” Russell said, referring to the refuge of the “Mutiny on the Bounty” crew.

*

At least one of Mounier’s alleged victims, San Fernando Valley resident Todd Schotanus, said the captain’s extended absence is but the latest example of federal officials’ failure to take the case seriously.

Yet as Mounier and his criminal case remain adrift, the civil battle over a controversial 1994 fishing expedition continues without him. A trial has been scheduled in federal court for September, although the plaintiffs say they are looking for a new attorney.

Russell has filed a countersuit accusing Mounier’s former crewmen of mutiny, and because the original suit names both Mounier and his corporation as defendants, the trial could go forward without Mounier himself present.

The unusual case, which has forced attorneys to immerse themselves in obscure maritime law, began in May 1994, when Schotanus joined Mounier’s crew while the Magic Dragon was docked at San Pedro Harbor.

Like many modern fishing captains, Mounier relied on seasoned first and second mates to anchor his crew but staffed his vessel with itinerant hired hands. Schotanus, an amateur sailor who had never been on an extended voyage, joined two other novices and one experienced seaman to round out Mounier’s crew.

The scheduled 40-day, 4,000-mile voyage began routinely, but as the weeks passed, Mounier began to act erratically, Schotanus and three other crew members allege in their suit. They claim that Mounier wore a pistol on his belt, proudly displayed pictures of previous crew members hogtied to the deck and eventually accused his four hired hands of stealing a candy bar.

He stopped feeding them, and they in turn refused to work, the suit alleges. The captain and his officers also confined the sailors to one narrow cabin, then turned up the heat to flush them out after four days of starvation, the suit says.

Schotanus and Jason Garinger, a resident of Portland, Ore., emerged only to be attacked by Mounier and his officers and handcuffed to the deck, they allege. The sailors were released when the Magic Dragon docked at San Pedro and was met by the Coast Guard, to whom Mounier had reported a mutiny.

Mounier told investigators that some sailors “are motivated by being slapped around a little,” according to Coast Guard records.

His lawyer says the crew members were money-grubbing landlubbers who committed mutiny rather than work, then sought millions of dollars in damages after the captain acted in self-defense. He said Mounier had to cut short his trip by several weeks and lost $50,000 in earnings--the sum he seeks in the countersuit.

“His state of mind is that the criminal charges are against the wrong party,” Russell said. “He’s a man that feels strongly that he’s the victim and that he’s lost a lot of money.”

Andrues dismissed Russell’s assertions that Mounier is simply trying to earn back money he lost in the abortive expedition. “That’s what his lawyer says,” she commented.

Federal officials missed two chances to detain Mounier as they were considering filing criminal charges. The first was when he cooperated with the Coast Guard in an unrelated case last summer, reporting an illegal fishing operation off the Hawaiian islands.

Coast Guard Lt. Scott Fleming, based in Honolulu, said Mounier’s vessel alerted the Coast Guard to the illegal drift-net scheme, where another boat was dragging a net through the ocean, scooping up protected species along with other fish. Authorities seized the drift-netting boat.

“I had heard . . . they were looking for him,” Fleming said. “That was back in L.A., where they were concerned about that. We view that as, that’s nice, but we’re working a high-seas drift net here.”

*

Russell said Mounier’s actions show he is concerned about the environment and maritime justice. In 1990, however, the U.S. attorney in Honolulu charged Mounier with harboring and concealing illegal immigrants and with killing both a humpback and a killer whale. Mounier pleaded to lesser charges of concealing information about illegal immigrants and transporting a killer whale and was fined $5,000.

Authorities missed another chance to question Mounier last September, shortly before his indictment, when he landed in Victoria, B.C., to give a deposition in the civil suit. Soon after, he headed back to sea and has not returned since.

“It’s frustrating to me, and I think the government and Mary Andrues in particular should be embarrassed that they did not take it seriously from the beginning,” Schotanus said.

Andrues refused to comment other than to say federal investigators believe Mounier is moving from island to island, staying in locations where he cannot be arrested or extradited.

She defended the 15-month gap between the day of Mounier’s return to San Pedro and his indictment, saying the case needed to be comprehensively investigated before charges were filed. She also would not comment on what the government is doing to catch Mounier.

Russell says he expects everything will end peacefully.

“He’s not public enemy No. 1,” he said.

More to Read

Sign up for The Wild

We’ll help you find the best places to hike, bike and run, as well as the perfect silent spots for meditation and yoga.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.