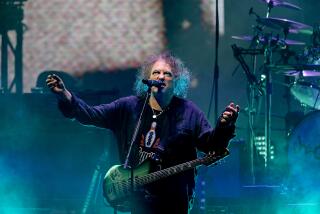

The Cure Finds a Remedy in Changes

- Share via

For most of the last decade, the Cure has seemed a band for which breaking up would not be that hard to do.

It’s not as if the band has been beset with rampaging egos or romantic complications. Apart from keyboardist Lol Tolhurst, who was forced out of the band in 1988 and later filed an unsuccessful lawsuit against front-man Robert Smith, the Cure has been relatively free of internal strife in its nearly 20 years of existence. If anything, Smith, bassist Simon Gallup, guitarist Porl Thompson and drummer Boris Williams always seemed more like buddies than bandmates.

Even so, rumors of the band’s demise cropped up with regularity, in part because Smith has often insisted that he never saw the Cure as a permanent fixture on the rock landscape.

In 1989, after dubbing the group’s 10th album “Disintegration,” Smith worried that some fans might take the title as a sign that it was the Cure’s last album. “But then,” he says, “I always think it’s the last album, so I don’t see why everyone else shouldn’t get that feeling.”

*

That feeling got a lot stronger after the band’s 1992 album, “Wish.” As a rule, the group cut a new album every other year, but when 1994 rolled around, not only wasn’t there a new Cure album, Thompson signed on for an album and tour with Jimmy Page and Robert Plant. Moreover, Williams announced that he was leaving. Suddenly, the band’s silence seemed even more pointed. Could the Cure have finally called it quits?

Hardly. The Cure’s membership may have changed over the last two years, Smith says, but its basic principle remains the same.

“The group--it’s really much more like a social thing,” he says by phone from the house in Bath, England, where the Cure recorded its new CD, “Wild Mood Swings.”

“Boris left a couple years ago but has actually been back to where we’re recording and played drums with us,” he says. “And then Porl’s my brother-in-law, so it’s no kind of acrimonious departure. On both counts, they left because, after such a long span of time in the Cure, they just wanted to try something else.”

Thompson’s spot was filled by Perry Bamonte, who had played keyboards on “Wish”; keyboardist Roger O’Donnell, who left before “Wish” was recorded, is now back in the fold. Williams was replaced by newcomer Jason Cooper.

But that’s not the only reason Smith calls the current Cure “a very different group [from] the one that made the ‘Wish’ album.”

“On the new record, we’ve used an Indian orchestra and a jazz quartet and a string quartet and Mexican trumpet players,” Smith says. “Everything on the album is real. In the past, I would have tried to keep it in the family, so to speak, and tried to attain a realistic sound through emulation or simulation. Now I feel much more comfortable having people around who are really good musicians. . . .

“I’ve never held that disingenuous punk ethic that we won’t play our instruments properly. Boris, particularly, is a phenomenally good drummer, and replacing him was the most difficult thing. Not only did we have to find someone who would fit, who would get on with us and understand what the Cure is about, [he] also had to be as good a drummer as Boris, and it took months finding someone.

“Because once you’ve had someone that’s that good, you can’t really take a backwards step. The audience expects us now to have a certain standard of playing. I like the idea of being able to play. I think it’s to be applauded. I despise people who revel in the ignorance of not being able to play their instrument. I think there’s a kind of pathetic side to it, really.”

More to Read

The biggest entertainment stories

Get our big stories about Hollywood, film, television, music, arts, culture and more right in your inbox as soon as they publish.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.