High Pay Phone Rates Prompt Callers’ Anger, FCC Action

- Share via

Jeffrey Shore made a long-distance call from a public telephone in April. The bill he received has prompted him to avoid pay phones ever since.

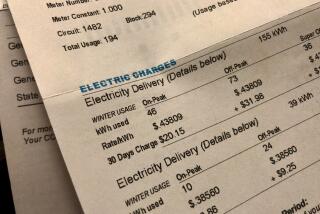

For a three-minute nighttime call--the type that would have cost about $1.50 with AT&T--he; was charged $7.60, including a $1.50 “use of phone” fee and a $2.50 “verification” surcharge.

Shore, a recent UCLA graduate, said he’s neither cheap nor a complainer, “but there was something about seeing a $7.60 bill for a three-minute call that really got to me.”

He’s not alone. Ever since pay phones were unplugged from Ma Bell in 1988, they’ve been the subject of a raft of complaints at the Federal Communications Commission.

Indeed, in the last year alone, the FCC received more than 5,000 complaints alleging excessive rates--a 25% increase from the year before.

In fact, the complaints have been so severe and so unrelenting that the FCC recently proposed rules that would govern how pay phone operators are paid and how pay phone users are charged.

The FCC’s proposals would require that long-distance providers disclose their fees--before calls are connected and charges incurred--whenever those charges significantly exceed the industry norm.

The federal agency is soliciting public comments and responses until Aug. 16. The FCC expects new rules would go into effect shortly thereafter.

Providers of long-distance service at pay phones contend that their high rates are often a product of market forces.

Some of these forces result from competition among the companies. To get a contract to install a phone, the companies must bid. Often, the owner of the site--the gas station, supermarket or hotel where the pay phone will be situated--will simply choose the highest bidder who will give them a piece of the action.

In long-distance hot spots such as airports and malls, the competition for that business can be fierce, causing costs--and rates--to skyrocket.

But rate considerations aside, the FCC is concerned that consumers have an easy way to tell what a call will cost.

How would the new FCC rules work? And how will they affect your next pay phone call? Here’s a rundown.

*

Q What has been proposed?

*

A The FCC has put forward two separate proposals.

The first is the key--it would require long-distance companies to orally announce their rates before calls are connected if these rates exceed standard rates by more than a set percentage.

The second is a technical plan that would alter how pay phone owners and operators are compensated for each call. By and large, these changes would be invisible to consumers. For example, where the pay phone owners now get nothing for a toll-free call, they may get some payment for providing access to the phone, although not directly from the caller.

*

Q How would the FCC determine what the standard rate is? And how much higher could the pay phone rate be before the company would have to disclose the cost?

*

A The FCC has tentatively decided to set standards based on the average rate charged for the same call by AT&T;, MCI and Sprint. If the call exceeds that average by 15%, the long-distance carrier would have to disclose the cost of the call--including any fees and surcharges--before the call is connected and the charges are incurred.

*

Q Why do you say “tentatively”? Is that how it will work or isn’t it?

*

A These are proposed rules that the FCC has put out for a 60-day public comment and response period. In some instances, the FCC could change its rulings as the result of the comments received. An earlier pay phone proposal that would have required pay phone operators to route each call to the consumers’ preferred long-distance carrier, for example, was nixed after the industry complained that the rule would be prohibitively expensive to carry out. In the current case, the proposed rules seem to have the support of most major players in the pay-phone debate. However, the 15% threshold could be changed, depending on both consumer and industry response.

*

Q When would this rule go into effect?

*

A That’s not clear, but regulators are aiming to put both the disclosure and new pay phone compensation rules into action in the fall.

*

Q Would this affect me if I make only local calls from pay phones?

*

A Not if you use change to make the call. These rules affect so-called 0+ calls in which you call collect and bill the call to your home number or to your credit card. Rates for cash-paid local calls are already fairly standard and completely up-front, because the phone system requires you to deposit money before the call will go through.

*

Q If I make a call with my telephone calling card, isn’t the call routed to the card-issuing carrier and billed at its rates?

*

A Not necessarily. Such calls are usually routed to the long-distance carrier assigned to the phone. You get charged via your regular phone bill, but the rates are set by the long-distance company used, not by the company whose card was used to generate your billing information.

*

Q Can I get to my own carrier from a pay phone?

*

A Yes. All long-distance carriers have toll-free access codes that you can use to “dial around” the long-distance company assigned to that phone. These access codes are usually listed on the backs of telephone calling cards. However, if you don’t know yours and it’s not there, call your phone company to get it, then keep the access code handy for your next pay phone call.

*

Q How do I find out what I’m paying to make a 0+ pay phone call before these rules go into effect?

*

A All pay phones are marked with the name of the local phone company that owns it--such as General Telephone or a Baby Bell such as Pacific Bell--and the name of the long-distance service provider. In addition, long-distance service providers must state their names orally before calls are connected, said Robert W. Spangler, deputy chief of the enforcement division at the FCC’s common carrier bureau. You can call the assigned long-distance company and inquire about its rates. (Its phone number should be posted on the phone.) If those rates are higher than you’d like--or if you can’t get an adequate response--you can dial around the long-distance company assigned to that phone by using your preferred long-distance carrier’s access number.

*

Q So what else should I know to be a smart pay phone consumer?

*

A Dialing your carrier’s code or 800 number puts you in a familiar system, which is always an advantage.

If you’re confused, you can always punch “00” to get the long-distance operator and ask about rates, fees and charges.

You can also avoid unpleasant surprises with long-distance charges altogether by buying a prepaid calling card. These are now issued by every major phone company and are available at grocery stores and other retail outlets.

Prepaid calling cards allow you a set number of minutes of long-distance calling for a set price. The per-minute costs vary widely--some issuers charge as little as 10 cents a minute and others more than 50 cents. For short calls, the cards are often cheaper than regular phone charge cards that have per-call minimums. Either way, you know the cost when you purchase the card.

Kathy M. Kristof welcomes your comments and suggestions for columns but regrets that she cannot respond individually. Write to Personal Finance, Los Angeles Times, Times Mirror Square, Los Angeles, CA 90053, or message Kathy.Kristof@latimes.com on the Internet.

More to Read

Inside the business of entertainment

The Wide Shot brings you news, analysis and insights on everything from streaming wars to production — and what it all means for the future.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.