Orthodox Leader Steps Down After 39 Years

- Share via

It was a crucial moment in American history. The 1965 memorial service had just concluded for a Boston minister beaten to death in Selma, Ala., by white toughs who could not abide the idea of a white man defending a black man’s cause. Standing beside Martin Luther King Jr., the bearded, black-veiled Greek Orthodox Archbishop Iakovos seemed like a visitor from another world, another time.

The Greek immigrant took his place among America’s religious leaders in the tense procession to the Selma courthouse. The assembly--Protestants, Catholics, Orthodox and Jews--moved as one body, firm in its resolve that if the children of God were in danger, there they would be.

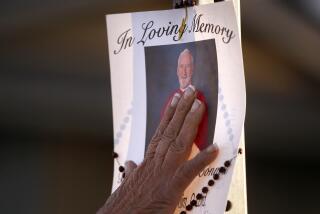

Thirty-one years later, on a rain-soaked day this week in New York’s Central Park, the 84-year-old Iakovos moved at the head of yet another procession--this one a liturgy of joy--as thousands of Orthodox Christians gathered there to mark the end of his 39 years as leader of the 5 million Orthodox Christians in the Western Hemisphere and to honor his efforts to bring the world’s religions closer together.

Clouds of incense drifted upward in the moist summer air and mingled with the sounds of hymns and Scripture chanted in the Greek language spoken by some of Jesus’ earliest followers. It was a mystical moment, and once again, the imperious and imposing Iakovos--wrapped in brocaded vestments and wearing a crown of gold--seemed a figure from another world, another time.

“Let us go forward on the road that has brought us to where we are,” Iakovos exhorted the crowd during the three-hour liturgy. “We also are called to be apostles. It is not for us to hide the rich tradition and truth of our church.”

Iakovos, whose Orthodox faith claims to be the most ancient form of Christianity, has also been the most modern of men. He has spoken out--often at his peril--against racists and warmongers, marching for civil rights, protesting the Vietnam War, embracing liberal as well as conservative political causes and bending the ears of presidents from Eisenhower to Clinton.

He is retiring reluctantly, under orders of his boss, the Ecumenical Patriarch Bartholomew I of Constantinople (now Istanbul), the preeminent leader of about 250 million Orthodox Christians around the world.

*

A synod of 12 high-ranking churchmen in Istanbul is expected to choose Iakovos’ successor July 30, the day after his 85th birthday, when his retirement takes effect. Among the top contenders are three North American bishops: Suterios of Canada, Maximos of Pittsburg and Anthony of San Francisco.

Still, Iakovos shows no sign of stopping.

“When I retire, I will not remain still or I will die,” Iakovos said in an interview. “I will use the time I have left to further my ecumenical work. I will elucidate the positions of the Orthodox church in America. It must be an active church and an activist church because the world today needs to be rearranged.”

In the nearly four decades he has led Orthodox Christians in the West, Iakovos has done much to reconcile the ethnic rivalries that existed among Greek, Russian, Ukrainian, Syrian, Antiochian and other national branches of Orthodoxy that have taken root here.

He also has helped rearrange the relationship between Orthodox and Catholic churches, separated since the time of the Holy Roman Empire because of Rome’s insistence on a standard Latin rite and the central authority of the papacy. The Orthodox have argued with equal insistence that the churches established by the apostles of Jesus in Greece, Asia Minor and the Balkans all remain autonomous, self-governing and culturally distinct.

In 1959, at the urging of his mentor, the late Ecumenical Patriarch Athenagoras, Iakovos initiated a historic meeting with Pope John XXIII, marking the first time since the 16th century that an Orthodox prelate had met with a pope.

*

‘It was an embrace of two old and long-separated sisters, West and East,” Iakovos recalled. And in his nine terms as co-president of the Geneva-based World Council of Churches, Iakovos orchestrated other ecumenical encounters between Orthodox Christians and Jews, Muslims, various Protestant bodies and historically black denominations.

“Iakovos has always been very clear on what Orthodoxy and the true Christian faith from their perspective is all about,” said Robert Tobias, a retired Lutheran ecumenical officer in Racine, Wis., who has worked with Iakovos on ecumenical issues since the 1940s.

“He was never antithetical to other beliefs, but he would also never surrender or compromise on the fundamentals of his own faith,” Tobias said. “He would tell us that unity is achieved by integrity, not compromise.”

That refusal to compromise the integrity of Orthodox belief and practice has brought Orthodoxy in the West to a crossroad.

As Iakovos steps down, the Orthodox church in the United States is on the cusp of transformation from an immigrant faith to one that has wide appeal to a variety of disaffected Christians seeking an anchor of authenticity in a sea of change.

Catholics put off by folk Masses that replaced traditional liturgies, Episcopalians disenchanted by liberal reforms, and evangelicals searching for a connection to Christianity’s roots have all been drawn to Orthodoxy. It is a trend religious scholars find hard to quantify, but contend is real nonetheless.

*

The fact that the Orthodox allow priests to marry also draws many converts to their seminaries.

“I’m in one sense astonished at how many American clergy are becoming Orthodox,” Tobias noted. “But the more I reflect on it the less surprised I am. People find a richness of liturgy and above all, theological solidity. There’s a depth that they don’t find elsewhere.”

While some religious bodies consider intermarriage a threat to their survival, the Rev. Anthony Ugolnick, a Ukrainian Orthodox priest who serves in a Greek Orthodox Church in Lancaster, Pa., sees intermarriage as another force to bring outsiders into the Orthodox fold.

“As a pastor, I’m very pleased with the number who marry Orthodox whom we retain,” Ugolnick said. “Most American churches are not strong enough to withstand an alliance with an Orthodox person. If the [non-Orthodox partner] is religious at all, they’ll join us.”

But the basic appeal, Ugolnick said, lies in the mystical and sensual appeal of Orthodox worship and its unyielding commitment to the founding principles of Christianity.

“We are a church that is militantly traditional and we’re not likely to change,” Ugolnick said. “We’re attracting people on the basis that we’re true to the teachings of Christ, in continuity with that ancient church. . . . We’ve proven that the tradition can be sustained in a truly American environment.”

That is not to say Orthodoxy is free of tensions. And while the Greek church mourns the passage of the Iakovos era, some priests, like Ugolnick, are glad to see it end.

*

‘It’s time for a change. Iakovos has done wonderful things. He’s a master orator, he’s represented us regally. But it’s time for Orthodox Christians to get some leadership that focuses on the needs of the people rather than on the banquets and displays of power that is the public face of the Greek Orthodox Church in the U.S.,” he said.

Tobias, whose forthcoming book, “Heaven on Earth: A Lutheran-Orthodox Encounter,” explores the appeal Orthodoxy holds for other Christian bodies, said Iakovos’ retirement marks the end of an era for the Orthodox in America.

“In Orthodox worship, you look at an icon and see the deeper reality. You see through the person into the depth, the richness, the stability and the whole ethos of Eastern Orthodoxy,” Tobias noted. “Iakovos has been that kind of icon for the religious community and the world.”

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.