The Half-Life of Albert Einstein : BIOGRAPHY : EINSTEIN: A Life.<i> By Denis Brian (John Wiley & Sons: $30, 509 pp.)</i>

- Share via

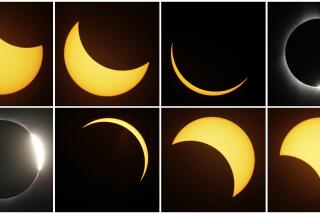

In 1919, the English astronomer Sir Arthur Eddington announced to the Royal Society that observations made during a recent solar eclipse supported Albert Einstein’s theory of relativity. Overnight, Einstein became a celebrity. Not just for 15 minutes and not just until the next Nobel Prize ceremonies but for the rest of his life, until his death in 1955.

When he arrived in New York aboard the Rotterdam in 1921, he was mobbed by reporters--and by photographers who, according to Denis Brian’s account in “Einstein: A Life,” yelled orders “like Army sergeants drilling new recruits.” Herr Professor Einstein was sought out for his opinions on matters small and great, intimate and geopolitical. He was loved as few public figures, much less scientists, ever are. He was also roundly hated by anti-Semites and those disquieted by the seemingly twisted new universe his theories implied.

Today, no scientist could hold the world’s attention even briefly the way Einstein did for almost 40 years, and by this phenomenon Denis Brian is clearly captivated. Let Einstein pose for a sculptor, issue a statement on the international situation or answer some reporter’s lame question and Brian gets it down. Einstein’s science, on the other hand--which in this book comes to us only secondhand, through the pronouncements of others--interests the author scarcely at all.

Indeed, Brian’s 509-page biography consigns Einstein’s ideas, including the theory of relativity, almost to a footnote. Moreover, it leaves his parents, his two sons, his wives Mileva and Elsa, not to mention the several other women with whom he had affairs, as shadowy and indistinct characters. Barely a hundred pages into the book, Einstein is already 40; he’s long past his greatest discoveries, into his second marriage and on the brink of scientific stardom. Indeed, “Einstein: A Life” is not about his life so much as that portion of it lived in the glow of celebrity.

To be sure, the way an illustrious scientist handles fame--his personal relationships, the role of a dutiful spouse in helping him, his efforts to shape his field long after he’s made his mark on it--all raise questions that might produce a substantial, if quirky, biography. Yet Brian does not confront such issues. Rather, he serves up stories, one after the other. Many are entertaining, but they add up to a shapeless clutter, united only by chronological proximity.

In one two-page span, for example, an 8-year-old girl shows up on Einstein’s doorstep for help with her homework and soon is being served lunch by the old professor, who heats up beans on a Sterno stove in his office; a physicist tells him of a new way of thinking about quantum mechanics; Einstein relates his views on travel: “Love to travel . . . hate to arrive”; Japan bombs Pearl Harbor; Nazi Germany weighs the merits of an atom bomb project; Einstein describes himself to a friend in Palestine as “a lonely old fellow . . . a kind of patriarchal figure who is known chiefly because he does not wear socks” and an Illinois man writes him for his endorsement of a stomach remedy.

This is all good fun, but do we need nearly 500 pages of it? Brian tells the stories well enough, sliding easily from one to the next. He recounts Einstein’s trips around the world, the Nazi rise to power, the atom bomb, the birth of Israel, the McCarthy years and his death. By sheer profusion alone, these stories do add up to something--a sense that we know a little more of what Einstein was like than we did before. But only a little more.

For any study of Einstein that excludes his intellectual life, leaving us with an image of him playing his violin, answering letters from around the world and, oh yes, sometimes scribbling equations, is a distortion. Reading Brian, the second half of Einstein’s life seems so full of afternoons sailing on the lake we wonder how the man got any work done at all.

Some critics, of course, might suggest he scarcely did. Later in life, Einstein stood outside the mainstream of physics, his unified field theory never fully developed. Could it be that, despite our view of Einstein as shy, solitary and bored with trifles, he was in fact sorely distracted by fame and the demands it made on his time? That celebrity exacted a terrible toll?

“For a self-proclaimed hermit, Einstein maintained a crowded hermitage,” writes the author of Einstein in his late 50s--complete with wife, live-in secretary-housekeeper, stepdaughter and nonstop flow of visitors. “Most weekends and vacations he spent with friends. . . . He was rarely physically alone. . . . Had he wished, he could have worked in solitary splendor,” and yet he didn’t. “So much for the hermit.”

Perhaps Brian detects a jarring dissonance in Einstein’s life. If so, he does not develop this theme. Here, as throughout the book, he tells story after story--but rarely reaches for what they mean.

More to Read

Sign up for our Book Club newsletter

Get the latest news, events and more from the Los Angeles Times Book Club, and help us get L.A. reading and talking.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.