THE NEW AGE AD

- Share via

Tennis star Gabriela Sabatini slammed the ball toward her opponent and dashed across the hard court surface at La Costa Resort--over a huge logo for Toshiba digital videodiscs--to prepare for the return.

At least, that’s what you saw if you were watching the second round of last month’s Toshiba Tennis Classic on the Prime Network cable TV channel. If you were in the stands at La Costa in Carlsbad, just outside San Diego, you saw Sabatini and Asa Carlsson playing on a pristine court free of corporate logos.

Fans of the San Francisco Giants have encountered the same mysterious phenomenon this year: Viewers of the team’s home games on Bay Area television see advertisements seemingly painted over the backstop. Fans in the stands see a clean, ad-free wall.

The era of “virtual advertising” is upon us. The craft of manipulating reality has finally achieved the ultimate illusion--creating the advertising image itself out of thin air.

New electronic techniques are allowing advertisers to insert their pitches into television images in a way that makes them indistinguishable from physical reality--right down to their being obscured by passing shadows or players in the foreground.

The system allows previously unmarketed portions of the television screen to be sold to advertisers who don’t even have to wait for breaks in the action to get their images before the viewers.

Thus the court surface at La Costa was sold to Toshiba, Lexus and the software maker Corel Corp.; the backstop at 3Com (formerly Candlestick) Park in San Francisco to Kellogg Co., Nissan Motors USA and GTE Corp., among others; and the space between the goal post uprights at one recent collegiate football game to computer maker Gateway 2000 Inc.

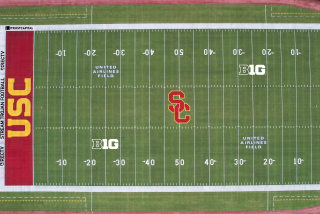

That’s only the beginning. Advocates of the technology envision using it to transform entire playing fields into digital billboards manifest only on your TV screen.

“There is no reason why a soccer field could not be a MasterCard or a Visa card with people playing on it,” says Bruce Maggin, executive vice president of ABC Multimedia Group, a unit of ABC Television.

No reason indeed, except that viewers might rebel. Concerned about jolting the audience, some advertisers are avoiding overly splashy ads. Sponsors of the Toshiba Tennis Classic, for instance, aimed for an understated look by displaying their logos in conservative black rather than color.

What’s more, virtual ads are expensive. At 3Com Park, the price of a virtual ad behind home plate can be eight times that of a 30-second local broadcast commercial, which goes for as much as $5,000. That’s because the virtual ads are sold by half-innings, which last longer than a TV spot.

This can make it hard to assess the relative value of virtual versus real. Nissan says it got its money’s worth from a virtual ad in a July 18 game between the Giants and Dodgers mostly because a crucial play was repeated on local telecasts and on ESPN, giving the ad unusually prolonged life. The auto maker hasn’t bought a virtual ad since, not only because of the cost, but also because of the limitations of a static image.

“We can get more of our message into a 30-second spot,” says Barry Liston, marketing manager for Nissan USA’s Northwest region.

Virtual advertising is done by electronically inserting images into a live TV broadcast, using the playing field as a map. Because a computer can detect players and other objects blocking the ad image from the foreground and make adjustments, the ads seem to be painted on the actual playing surface.

To some sports fans, this may represent the ultimate encroachment of advertising into athletics--going well beyond the recent innovation of naming sports arenas and even bowl games after high-paying corporate sponsors.

“I think people accept that they are going to see advertising,” says Michael Kamins, associate professor of marketing at USC. “The issue is whether they see too much of it. And the answer is yes.”

Even some TV executives question whether the technology goes too far. NBC, for example, chose not to insert ads into its Aug. 25 broadcast of the Toshiba tennis finals, in which Kimiko Date defeated Arantxa Sanchez Vicario.

“The technology is pretty neat, but once you get past that you ask yourself, does it really enhance anything at all or is it just another way to slice the [revenue] pie?” says John Miller, senior vice president of programming at NBC Sports. “It certainly doesn’t enhance the viewers’ experience at all.”

To the broadcast industry at large, however, the technology represents an enticing new source of income at a time when established sports are demanding skyrocketing broadcast fees from networks and other telecasters.

Some television executives even contend the technology is a tool against channel surfing. With revenue from virtual ads, they argue, broadcasters won’t need to air as many commercials, thus reducing the breaks in the action that give viewers an excuse to click the remote.

“Using signage between the [football] goal posts in an extra point or field goal allows an advertiser to have an association with the event without breaking into the action,” says ABC’s Maggin. “It is my contention that one of the great advantages of billboard insertion is that we can eliminate the need for station breaks during sporting events.”

How people in sports feel about the ads depends to some extent on whether they get a piece of the action. The Giants are thrilled with virtual advertising; they split the revenue with broadcasters. (By contrast, they receive no revenue from traditional signs erected inside 3Com Park, which is owned by the city of San Francisco.)

Teams that profit from traditional stadium billboards, on the other hand, view virtual ads as an invasion of their lucrative turf.

Objections from the Big East college football conference caused the ESPN cable sports network to pull the plug on virtual ads scheduled for a game between the University of West Virginia and the University of Pittsburgh over Labor Day weekend. Virtual signs scheduled by ESPN in the Big 10 conference game between Purdue University and Michigan State University that weekend were also dropped.

ESPN acknowledged that previously scheduled virtual ads did not run in either game, but it said that was due to “minor problems.”

Those conflicts reflect a tug of war that has gone on for years between the colleges and the networks. As Thomas McElroy, assistant commissioner of the Big East, observes, the colleges have long agreed not to erect temporary billboards in their end zones because the networks don’t want stadium advertisers to ambush paying sponsors.

*

But he warns: “If they are going to create signage where it doesn’t exist, then they are inviting athletic directors to create their own end-zone signage.”

Advocates of the technology believe such disputes will be worked out. They argue that sporting events will eventually command higher broadcast fees because the technology will allow networks to sell more advertising time, even with a reduction in commercial breaks.

Indeed, the less prestigious Western Athletic Conference has agreed to let ESPN pop virtual ads into its college football games.

“There are ownership issues, there are rights issues,” says WAC Commissioner Karl Benson, noting that a Gateway 2000 billboard showed up in the Labor Day weekend contest between Boston College and the University of Hawaii. “But we . . . think it could mean potential revenue for the WAC.”

It could also mean a potential windfall for several companies geared up to create virtual billboards, including the venture that developed ads for the Toshiba Tennis Classic, SciDel Technologies. That firm, formed by Scitex Corp., an Israeli maker of digital printing equipment, does not sell ads itself but earns a fee for creating them on computers. (It’s not yet profitable.)

The system has its drawbacks. A glitch kept it from working during the first set of Sabatini’s match. Also, it is easily confounded if too many objects appear in the foreground, as would happen on a soccer or football field crowded with athletes. Currently it is suitable only for tennis.

Of course, suitability remains a matter of taste. NBC’s Miller, having viewed the ad-laden Sabatini match, found the ads distracting.

“I thought the sign was enormous out on the court, and I do not think the tennis viewer wants to see that on the playing field,” he says. “Especially signage that’s changing.”

(BEGIN TEXT OF INFOBOX / INFOGRAPHIC)

How Virtual Advertising Works

A handful of companies are using electronic imaging techniques during sporting events to put up “virtual billboards.” Visible only to TV viewers, the ads appear to be painted on stadium walls or playing surfaces, but they exist only on the TV screen. Unlike traditional stadium signs, the billboards can be changed many times during the course of an event. Here’s how virtual signs ended up in the Aug. 22 telecast of the Toshiba Tennis Classic.

1. The Scitex Corp., virtual broadcast feed--the basic image to be sent to viewers--from NBC which produced the event.

2. Once it received the feed, the system scanned the playing surface, recording its dimensions and noting the location of visual obstacles such as shadows and players.

3. At the same time, a technician watched the match on a video monitor and selected a logo, foreshortened to match the background, for insertion into the telecast.

4. When the camera angle was right, the system “mapped” the logo into the broadcast.

5. The broadcast feed, now containing the logo, was transmitted back to NBC, which beamed it via satellite to Prime Network in Houston. Prime Network distributed the telecast on its sports cable channel.

More to Read

Inside the business of entertainment

The Wide Shot brings you news, analysis and insights on everything from streaming wars to production — and what it all means for the future.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.