Apartheid-Era Killer Details His Crimes

- Share via

PRETORIA, South Africa — Eugene De Kock, the apartheid regime’s most notorious assassin, publicly detailed his role for the first time Monday in the deaths of scores of anti-apartheid activists in the 1980s.

But the former death squad leader, who was convicted of six murders and 83 other charges last month, offered no apologies and showed no remorse as he testified in court for mitigation of sentence.

Indeed, the head of the infamous police counterinsurgency unit at Vlakplaas, a grassy farm west of Pretoria, boasted of his macabre exploits--from kidnapping to sabotage. He said, for example, that he secretly provided anti-apartheid guerrillas with grenades that would explode as soon as the pin was pulled.

“The idea was to kill them all,” he explained calmly.

His lawyer, Flip Hattingh, questioned the slow, unemotional recitation of murder and mayhem. “You sound so cold and clinical,” he told his client.

De Kock agreed, saying he had learned to hide his emotions. “It’s something you keep to yourself,” he testified. “You cannot cry, because everyone will cry with you.”

Hattingh said later that the defense hoped to prove that De Kock acted under orders from his superiors and that he was only fighting as he had been taught in previous service as a covert commando against black liberation forces in what are now Zimbabwe and Namibia.

“He was trained and used to fight terrorists,” Hattingh said.

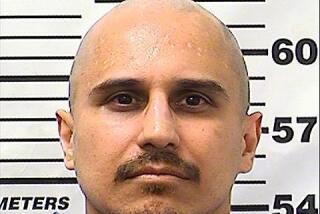

The face of “Prime Evil,” as De Kock was known to his colleagues, is owlish and pudgy, framed by heavy square-rimmed glasses and a bad, prison-issue haircut. At 47, he is a bullish, no-necked man with broad shoulders and thick arms that bulged in a tight gray suit. His voice is surprisingly soft.

De Kock said then-President Pieter W. Botha “no doubt . . . knew about” his hit squad operations in the mid-1980s. He named several senior police officials as authorizing the raids, including a general who he said balked when they met. “He said, ‘I don’t know if I should shake your hand, it’s so full of blood.’ ”

Members of the post-apartheid government are eager to hear whom else De Kock will implicate. Safety and Security Minister Sydney Mufamadi and Deputy National Intelligence Minister Joe Nhlanhla attended the daylong hearing in the Transvaal Supreme Court.

De Kock said he was raised near Johannesburg by a strict Afrikaner father, a local magistrate who belonged to a pro-Nazi organization and who never questioned the white supremacist regime. “I had a Christian education, very strict,” he said. “There was no time for games. I had to do everything for myself. School holidays I worked on farms doing hard labor.”

He joined the South African police in 1968 and was sent to fight in support of the embattled white government in Rhodesia, now Zimbabwe. The capture and execution of several colleagues left a lasting impression, he said. “I decided you must shoot first and ask questions later,” he testified. “Shoot second and you die.”

In 1977, the young lieutenant transferred to a South African counterinsurgency operation in South-West Africa, now Namibia. He soon joined a clandestine guerrilla unit called Koevoet, which used local blacks to track and fight the rebels.

In all, De Kock said, he participated in at least 300 skirmishes or battles. He said he stopped taking prisoners after his superiors complained. “Everyone captured . . . was executed,” he explained, adding: “You didn’t just shoot people. You would run them over.”

But De Kock’s chief complaint was corruption. Money promised as bounty for each rebel head disappeared, while other officers asked him to sign false invoices. Even meat intended for the soldiers’ mess was sold to local shops, he complained.

After several confrontations with his superiors, he was stripped of command and sent back to Pretoria in May 1983. There he battled severe nightmares and panic attacks. His doctor diagnosed post-traumatic stress syndrome.

The cure came in his next assignment: the South African police counterinsurgency unit at Vlakplaas. The enemy was the then-banned African National Congress and other anti-apartheid groups.

Over the next few years, he said, he led numerous cross-border raids--sometimes involving abductions--against reputed ANC houses in neighboring Swaziland and Lesotho.

Only one operation gave him pause. He said he was ordered to kill three men in Swaziland without ever learning why. “I don’t know why they were killed,” he said. “There wasn’t even a fight. It was just a very dirty part of our work there.”

De Kock’s testimony was surprising since he appeared to be admitting to murders for which he has not been charged. Under South African law, however, he cannot be directly charged with murders that occurred outside the country.

De Kock will testify at least one more day before prosecutors begin cross-examination. The prosecutors are expected to ask about testimony during the trial that implicated the Vlakplaas unit in bomb blasts at three ANC offices in South Africa, as well as a bombing at the ANC offices in London.

De Kock has applied for amnesty from the country’s Truth and Reconciliation Commission, which is investigating political crimes of the apartheid period. But many of his convictions may be ineligible since he lined his own pocket with police funds. When he was arrested in late 1994, he had bank accounts in Switzerland, Britain and Portugal.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.