The Monkey God and I

- Share via

Once upon a time, for a few fleeting hours, I was a god. But it wasn’t as much fun as it sounds. Or nearly as ego-gratifying.

Back in the 1970s, the overland route from Turkey to India offered a fine catalog of horrors--the sort of experiences travelers find useful in their endless games of agony one-upsmanship. The 5 1/2-month, low-rent grand tour I took at age 19 provided a bountiful sampling.

But only one of my misadventures on that trip qualifies as uniquely my own--the time I was worshiped as the mighty Hanuman.

As it happens, that rather serious cultural misunderstanding resulted from a smaller one.

I was riding in the cheapest section of an Indian train coach, as an old British steam engine pulled us through a landscape sweating under monsoon skies. Sooty smoke poured in the open windows. The faces of several young men who couldn’t fit inside stared at us through the lowered glass as they clung to the side of the train.

Somewhere on that leg of the trip an Indian man wriggled into the seat beside me. He said he was an English teacher and was returning to his remote village for the first time in years. He struck up a conversation about India’s sainted nonviolent revolutionary, Mohandas K. Gandhi.

I was flattered that he took my Philosophy 101 grasp of Gandhi’s beliefs so seriously. Only later did he explain that he assumed I had dedicated my life to the Mahatma because of the two bare feet embroidered on my striped T-shirt.

To him, they were the universal symbol of Gandhi’s humility. Humbled indeed, I explained that in my culture--post-adolescent Californian--the feet were the trademark of a surf-wear company: Hang Ten.

*

In a sincere effort to foster cultural understanding, my new friend invited me to accompany him on his journey home, and early the next morning we got off the train at a tiny town, the name of which remains lost in a misplaced travel diary.

My friend had business to attend to, and we agreed to meet again in a few hours for the four-hour hike to his village. I set out to explore the town.

Quickly, I began to draw a crowd. At most train stops, swarms of children greet travelers with the beggars’ scream, “Baksheesh!” I had also grown accustomed to stares when I ventured off the usual tourist routes into places where pale-skinned Westerners were uncommon.

But this was different. Each time I paused as I strolled down this town’s dusty streets, a growing throng of children dropped to the ground at my feet and stared. Soon I noticed that they, and a few adults, were looking from me to another figure and back again.

The man was ancient, with long white hair and a white beard. His skin was weathered to the texture of a water buffalo and the orbs around his dark irises were yellowed from a lifetime in the subtropical sun. Even with a headache beginning to blind my own vision, I could see the cataracts fogging his. And the tears streaking his cheeks.

*

Under normal circumstances, I would have had a hard time figuring out how to contend with these circumstances. As it happens, though, just a day or so earlier, I had begun to notice a change in my health.

I’d cut my foot in Afghanistan, and although I didn’t know it yet, the cut had become infected. A few days later, a doctor in Bombay diagnosed the serious blood disease septicemia. As I strolled through the village, the problem in my foot was already telegraphing warning signals to my brain in the form of increasingly severe headaches.

Distracted by the pain, I found the children’s focus all the more unnerving. Understanding the situation became a serious challenge.

So I stood there like the village idiot, then kept walking, hoping movement would transform me back into a tourist sightseeing.

Each time I stopped, though, more children clustered, transfixed by me and the way the old man watched me. Now and then the old man murmured in Hindi, his tremulous voice choked with emotion. When he finally reached out and touched me, the children recoiled as if expecting a bolt of lightening.

Instead, I awkwardly offered my hand. He knelt at my feet. My pale face pinkened. He cried.

About this time, a couple of men in business attire joined the procession and assertively intervened. They gestured at the old man. They laughed. They tried to shoo the children. Finally, one of them spoke to me:

“This old man thinks you’re the god he worships. He’s lost his mind. But the children don’t know whether to believe him.”

*

Eager to expose the old man’s foolishness, one of the gentlemen took my elbow and tugged me through the swarm. We walked, with the children and the old man trailing, down an alley to a tiny storefront in a squat building made of adobe-like mud. It was the old man’s pathetically understocked dry goods shop. The younger man pointed inside.

A multitude of deities inhabit the Hindu pantheon--333 million it is said--and many homes and businesses display cheap, brilliantly colored posters depicting scenes from the Hindu faith’s fabulously intricate mythology. Most of these slick paper prints display scenes from the life of the dusky blue deity Krishna, or whatever god the individual worships--from the obscure to such important figures as Shiva, Vishnu or Ganesha, the elephant-headed god.

As we gazed into the old man’s shop, the children squealed with laughter and pointed at the posters decorating the walls. Each was a tribute to a very distinctive-looking god, whom I have since concluded was Hanuman, an honored compadre of the god Rama.

The old man, it became clear, believed that I was Hanuman, returned to the physical realm from the third dimension where gods usually reside.

In a way, the mistake was flattering. Hanuman is a great warrior, a powerful slayer of demons who fought loyally beside Rama in many cosmic battles.

On the other hand, Hanuman is, well . . . a monkey.

*

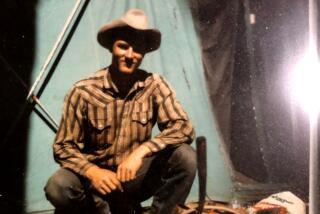

The hard part of this, I’m chagrined to say, is that the old man’s comparison was not entirely unlikely. Back then, I wore my sun-bleached red hair past my shoulders and sported a tumbleweed beard that a friend had labeled “hideous.’

Most images of Hanuman that I’ve seen since then depict him as bluish-gray with flowing black hair and simian jowls. But the old man’s posters made him look more like the monkeys that haunt so many Indian temples--cascades of auburn hair and a beard.

The gathered crowd, kids and adults alike, turned riotous as they noted the similarities and chattered with wild laughter.

Eventually, my friend returned and we set out on the long hike. The entourage, including the old man, fell behind at the edge of town. That night, my friend’s family, and the people of his village, treated me not as a god but a welcome guest. Their hospitality was a highlight of my journey. The next day, we retraced our route, hiking under clouds pierced by blistering spears of sunlight.

*

Back in town, the novelty of my presence had faded. Only a few children accompanied the old man when he spotted me and again attached himself to my side. With my friend interpreting, I again explained that I was not a god, but a standard-issue college vagabond.

Apparently much was lost in translation, and when my friend finally caught his train back toward New Delhi, the old man remained undeterred.

Fading, I lay on a scrap of brown lawn beside the tracks, my head propped against my backpack. The old man sat beside me, apparently praying.

By now, the invaders in my bloodstream had gained strength. A microscopic battle raged inside me. The devils of infection stormed my brain, banging loudly as if striking swords of pain against the shields of a defending army.

Before long, I lost consciousness.

When I awoke to the steam engine’s whistle, the old man was gone.

More to Read

Sign up for The Wild

We’ll help you find the best places to hike, bike and run, as well as the perfect silent spots for meditation and yoga.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.