Medical Advances Brighten Outlook

- Share via

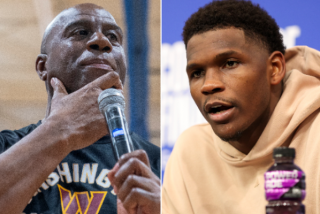

The five years that have passed since Magic Johnson was found to be HIV-positive have been marked by what can only be called a revolution in the care and treatment of AIDS patients and in the fundamental understanding of AIDS itself.

In early 1991, physicians had only one drug, AZT, to treat AIDS patients, and there was great debate over how best to use it. Little was known about how the virus invaded cells and replicated in the bodies of its victims, or about why some people who were repeatedly exposed to the virus seemed immune to its predation.

Infection with the human immunodeficiency virus was widely considered tantamount to a death sentence.

No longer.

“Anti-HIV treatment is dramatically better than it was five years ago,” said Dr. David Ho of the Aaron Diamond AIDS Research Center in New York, a leading AIDS researcher and Johnson’s personal physician. Physicians now can choose from nine antiviral drugs to provide the best individualized therapy for each patient. Newer drugs on the horizon, based on an improved understanding of how the virus reproduces, promise even greater effectiveness.

A new understanding of the viral life cycle during the early stages of an infection has also convinced clinicians that it is crucial to attack the HIV as soon as possible, before significant damage can be done to the immune system. They are using so-called cocktails of drugs that can halt replication in its tracks.

Such treatment, many believe, is capable of converting an HIV infection from the short-term, lethal disease it was five years ago into a chronic, manageable disorder not unlike diabetes or heart disease.

“Without a doubt, the situation has changed,” says Dr. Anthony Fauci, head of the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases.

In 1993, there were 45,992 AIDS-related fatalities in the United States, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. That number decreased to 32,505 in 1995.

“The future looks much brighter now,” added Dr. Ronald T. Mitsuyasu of UCLA’s Center for AIDS Research and Education.

Still unsettled, however, are two of the peripheral issues relating to Johnson’s off-and-on participation in professional sports: the effects of intense, competitive physical activity on the progression of an HIV infection and the risks to other players.

Although most physicians believe that exercise is beneficial for HIV-positive people, and Johnson seemed to show no ill effects from his brief forays back into professional sports, many still question whether extreme exercise might not have deleterious effects in the long run.

“Exercising to the point of exhaustion would, I think, be ill-advised for the average person with HIV,” said Dr. Christopher Matthews of UC San Diego. “But the scientific literature is very incomplete.”

Most experts also believe that, with the possible exception of boxing, there is little risk of one athlete infecting another. “There are no documented instances of anybody acquiring HIV infection because of athletic competition, on any field of play, in any sport,” said Dr. Peter Drotman of the CDC.

But the bottom line for both exercise and transmission, as with so many other things connected to the AIDS epidemic, is that researchers simply do not know for sure. And much depends on the individual. Johnson is, in many ways, an exceptional individual, both in his good health when the infection was first detected and in his overall attitude toward life.

He was fortunate that the infection was detected during a routine blood test. Ho immediately began therapy with AZT, the only drug then available. Within the first year, he added a second medication-- a “reverse transcriptase inhibitor”--to Johnson’s drug cocktail. Ho would not name the specific drugs Johnson is taking, he said, because, “We do not wish to endorse any particular drug.”

When the first results with the new family of drugs called protease inhibitors became available early this year, one of those was also added to the regimen. Johnson now takes four to six pills twice a day. Unlike many others undergoing triple therapy, he does not suffer any of the side effects normally associated with it.

Johnson does occasionally slip up and forget to take a dose of medication--an event feared by doctors because it increases the risk of developing a drug-resistant strain of the virus. “I’m only human,” he said. “I might be going somewhere on a plane and forget to take my pills. . . . But it’s very seldom when I forget. I’m a disciplined person.”

Since Johnson has been on triple therapy, Ho noted, the amount of virus in his bloodstream has remained below detectable levels. That doesn’t mean he is cured: The virus is still present in lymph nodes and perhaps other tissues as well. But it does mean that the HIV is not replicating and ravaging his immune system, as it does if left untreated during the earliest stages of an infection.

His CD4 cell count, a common measure of immune system function, “has been maintained in good range for the past five years,” Ho said.

Ho and other doctors monitored Johnson closely when he was playing basketball and could see no changes in any immune parameters during that period. “I was like this guinea pig running around, this test-tube baby,” he said. “And basically I still am.”

Johnson said he was monitoring his health as closely as the doctors were. “And when nothing changed, when I was still able to run and do everything without getting tired, then that settled that. It put my mind at ease.”

But Johnson was still an experimental group of one, and it is hard to generalize from one case. “I don’t think we can say we’ve gained any scientific evidence” from studying him, Fauci said.

“But what we did learn is something important, something that really transcends things like the level of virus, CD4 count and so forth. And that is, with a positive attitude, people who are HIV-positive can do whatever their body allows them to do. That’s much more important than understanding what effects exercise might have on T-cell counts.”

For most of HIV-positive individuals, however, exercise is almost certainly helpful. “There is no question from my own clinical experience that moderate exercise programs appear to benefit people with HIV, particularly those [whose immune systems are not compromised] or who have lost lean body mass,” UCSD’s Matthews said. Such exercise improves psychological well-being and reduces stress levels, he added.

Some scientific studies suggest that exercising can increase levels of CD4 cells, the immune cells that destroy HIV. Others hint that it might have the opposite effect, suppressing CD4 activity. But, Mitsuyasu added, “I am not aware of any research going on” to answer those questions. “There are probably other issues that are more pressing.” Nevertheless, most doctors recommend exercise.

Most researchers dismiss the risks of transmitting the virus during athletic activity. Drotman and his colleagues at CDC estimated the risk for a football player in the NFL. Assuming that the incidence of infected players is about the same as that among young men on college campuses, about one in 200, they concluded that the risk of infection was about once in every 85 million plays.

For an HIV infection to occur, Drotman said, “it takes very specific circumstances. You have to have an infected person, he has to be bleeding, he has to make contact with an uninfected person who has a portal of entry [such as his own wound] and a sufficient dose of virus has to enter the system. That combination is pretty rare.”

The CDC and other groups have drawn up AIDS guidelines, which have been adopted by most organized sports, professional and amateur. They recommend that bleeding be attended to whenever it occurs and that participants who are bleeding should have the wound covered before they continue to play. “There is no need to test individuals and exclude people from play,” Drotman said.

The major exception to these rules has been professional boxing, which has taken the opposite tack of testing boxers and excluding those who are HIV-positive, rather than treating bleeding as it occurs.

“Testing and excluding is perhaps debatable,” Drotman said. “But it is absolutely certain that not taking care of people who are bleeding is a very bad health decision.”

As for Magic Johnson, he says he is excited about all the new developments and the fact that doctors can now offer more hope. “There’s no question about it. They’ve learned a lot in the last five years,” Johnson said. “Doctors and scientists from around the world are working together and gathering at summits to combine their knowledge and trade information. A lot has changed. For the better. For the good.”

Times staff writer Steve Springer contributed to this story.