After Finding a Cure for Boredom, Biologist Tackles Genetics

- Share via

Luis Villarreal did not grow up pondering the riddles of human existence.

He grew up in the rough and ragged streets of East Los Angeles, spending his high school years pondering the intricacies of motorcycle engines.

That he is now pushing out from the edge of what is known about the genetic mechanisms of the human body is more a result of boredom than ambition, as he tells it.

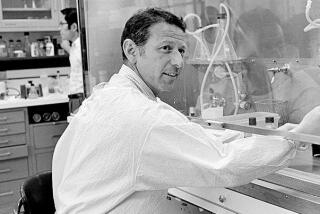

“I never envisioned myself doing what I’m doing now,” said Villarreal, 47, a UC Irvine molecular biologist who founded the Center for Viral Vector Design on campus five months ago. “I sort of backed into this career by avoiding all the things I didn’t want to do. Somehow, I ended up doing this.”

The center is a workshop of sorts, where Villarreal and other researchers are developing specialized viruses to be used as “vectors,” or delivery systems, for genetic material cloned in the campus lab.

The advances of recombinant DNA technology during the last two decades have raised public expectations that such gene transfers will soon provide a cure for a number of inherited and acquired diseases. But the creation of a biological delivery system that will effectively counteract genetic deficiencies and not be rejected by the human host remains a significant problem, said Villarreal, who finds the challenge a sufficient cure for boredom.

“I’ve always been curious about how things work. I’ve been a tinkerer forever. When I was a kid, I took apart my brother’s 10-speed bike, including the derailleur, and hundreds of ball bearings fell all over the garage floor. Somehow, I managed to get it all back together. I guess that’s a characteristic I have that has been useful in problem-solving.”

Villarreal’s flair for improvisation was not always appreciated. In high school, his ability to devise solutions to problems on a physics exam was called into question.

“I used a method that I now know is called analytical geometry, but I didn’t have a clear sense of what I was doing back then,” he said. “I analytically determined what the answers should be, and I got the highest score in the class by doing that.

“If I had a student these days who had come up with an innovative way to solve a problem like that, that would be someone to really encourage. But in my case, I was told, ‘There’s no way you could have beat these other students because you have not taken trigonometry. You must have cheated.’ ”

Villarreal grew up in a family of three brothers whose parents had not gone beyond the fourth grade. After high school graduation, Villarreal enrolled at a community college, looking for the training that would earn him a steady job as a medical technician.

“After one year of taking courses at a junior college, I was bored to tears with it. It was just memorization.”

His search for intellectual intrigue led to a bachelor’s degree in biochemistry from Cal State L.A., a doctorate in biology from UC San Diego and a research fellowship in 1976 with genetic researcher Paul Berg at Stanford University, who won the Nobel Prize in chemistry in 1980 for his pioneering work.

Shortly before Villarreal arrived at Stanford, Berg had called for a moratorium on genetic research over concerns about the potential for abuse.

Though the scientific community’s fears have largely been assuaged, Villarreal said there is a persistent public perception that genetic engineering amounts to a violation of the laws of nature.

“The prevailing public view of people in science is the stereotype of the mad scientist. Yet, if you look at the contributions of scientists toward the well-being of the planet, they’ve been very active.”

He tells the story of a parasitic wasp that doesn’t make nests.

“When they find an insect larva, they inject an egg into it and the egg will develop inside it. In order to grow in another organism, you have to turn off the immune system of that organism.

“And the way the wasp does it is that it makes a virus that gets into the larva and turns off the immune reaction in the insect larva so the egg can grow. That’s gene therapy. People keep thinking they’ve discovered things that nature hasn’t done. Then we find out, sure enough, it is a natural process after all.”

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.