A Victim’s Plea for Justice

- Share via

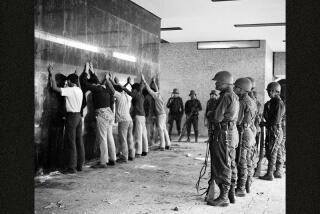

Five years ago this week, Indonesian soldiers armed with M-16 rifles made in the United States shot and killed my good friend Domingos Segurado at the Santa Cruz Cemetery in Dili, the capital of East Timor. He was the last member of his family; Indonesian soldiers had killed both his parents and all his siblings years earlier.

My wife, Gabriela, was also at the cemetery on Nov. 12, 1991. She was in front of the cemetery gate, buried under a pile of bleeding bodies. Gabriela was almost seven months pregnant with our son, but somehow she escaped by climbing over the cemetery wall.

Gabriela was fortunate. Hundreds died that day at Santa Cruz and in its aftermath as Indonesian soldiers killed many of the survivors. To this day, the Indonesian government has not disclosed the burial site of any of the dead.

Domingos and Gabriela were just two of thousands of people gathered at the cemetery that morning to pay tribute to a pro-independence activist killed by the Indonesian military two weeks earlier. Never in the 16 years of Indonesia’s reign of terror in my country had such a public display of pro-independence sentiment taken place.

I was 12 when the Indonesians invaded East Timor on Dec. 7, 1975, just nine days after we declared independence from Portugal and only hours after U.S. President Gerald Ford and Secretary of State Henry Kissinger met with Indonesian dictator Suharto in Jakarta, Indonesia’s capital. During the meeting, by all accounts, the United States gave Suharto the go-ahead to invade East Timor. Kissinger publicly stated that the U.S. “understands Indonesia’s position on East Timor.”

My family and I spent almost three years in the mountains hiding from the Indonesian military. Until mid-1977, two-thirds of the East Timorese people were struggling to survive as we were, in territory free from Indonesian control. But then the Carter administration provided the Indonesian military with U.S.-manufactured OV-10 Broncos. These counterinsurgency aircraft allowed Indonesia to bomb and napalm the population into submission.

When the Indonesians captured my family in September 1978, we were all suffering from malnutrition; some of us were close to death from dysentery. But we considered ourselves lucky because before we were taken away, we saw dead and decaying bodies everywhere. We saw crying children who had lost their parents or whose parents had abandoned them in the insanity of the war.

At that time, an Australian government report described Indonesia’s practice in East Timor as “indiscriminate killing on a scale unprecedented in post-World War II history.” By the early 1980s, more than 200,000 people--about one-third of the preinvasion population--were dead as a direct result of Indonesia’s war.

I helped to organize the march to the cemetery that November, but I could not participate. I was in hiding from the Indonesian military, which had uncovered my role as the leader of the underground resistance and was planning to kill me. Several months later, I was able to escape to Portugal.

What made the Santa Cruz Cemetery massacre unique was not that it occurred, but that Western journalists witnessed it. Reporters’ accounts and video footage of Indonesia’s brutality led us to hope that countries that had long supported Indonesia’s occupation, especially the United States, would stop sending economic and military aid to the Suharto dictatorship.

The U.S. government immediately condemned the massacre. But Allan Nairn, an American journalist who witnessed the shootings and was beaten by Indonesian troops, found (in a document he got from the State Department through the Freedom of Information Act) that on Dec. 10, 1991, U.S. officials privately told senior Indonesian military commanders that Washington “understand[s] Indonesia is under considerable pressure from the world at large . . . [and] we do not believe that friends should abandon friends in times of adversity.”

President Clinton once described past U.S. policy toward East Timor as “unconscionable.” And while grass-roots and congressional pressure has forced the administration to ban the sale of small arms, helicopter-mounted weaponry and armored personnel carriers to Indonesia, little else has changed. Under Clinton, the U.S. has provided Indonesia with almost $400 million in economic assistance and authorized the sale of $470 million worth of weaponry. Now the administration is trying to sell nine F-16 jets to Jakarta.

The awarding of this year’s Nobel Peace Prize to Jose Ramos-Horta and Bishop Carlos Felipe Ximenes Belo of East Timor has renewed hope among the Timorese people. The Clinton administration and Congress should follow the Nobel committee’s lead and end U.S. support for Indonesia’s brutality in East Timor.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.