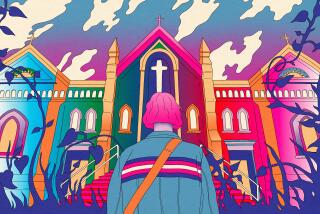

‘Seekers’ Find Churches Fill Spiritual Void

- Share via

CINCINNATI — Price and Kimberlyn Headley are, in 27-year-old Kimberlyn’s words, “good kids.”

They are committed to each other and to their four-year marriage. They work hard and rely on themselves, saving and investing conscientiously. They are caring and honest and have sought, said 29-year-old Price Headley, “to live up to a higher standard” than what they see around them.

“We do all the right things,” said Kimberlyn Headley. “It ain’t ‘Leave it to Beaver,’ but it works for us.”

So it wasn’t exactly a crisis of personal values that drew the Headleys to church. But something was missing. Something deeper. Something spiritual.

They think that they have found it in the auditorium of the Walter Peoples Middle School, where a melting pot of religious dropouts, former agnostics and other “unchurched” people meet every Sunday morning in the makeshift home of Crossroads Community Church.

For the Headleys, Crossroads fills a void at two levels: Accepting God makes them feel they are not alone in the universe, and finding 31-year-old Pastor Brian Tome and this hip, young community of Christians makes them believe that they are not alone in America either.

“I wanted to find a body of people--if they were out there--that were good people, thinking people,” said Kimberlyn Headley. “God, for me, is a very personal issue. But I feel very strongly in my belief, and I want that appreciated and not mocked. I wanted to find someplace where we would feel comfortable and definitely be appreciated for living pretty moral lives.”

The Headleys have joined a vast flock of “seekers” who are turning to organized religion, often after years of absence and in some cases for the first time in their lives. In a period when more Americans than ever believe that the nation’s values have run aground, the Headleys and their fellow seekers are filling the sanctuaries of the nation’s churches, synagogues and mosques in record numbers.

Their spiritual odyssey speaks volumes about the nation’s debate over values and the role of organized religion in it. Many seekers say that their lives are being changed for the better by religion and that their pilgrimage is changing religion in the process. It has given rise to new categories of churches and new approaches to winning converts. It is prompting many churches not only to provide seekers with spiritual guidance but to re-create the sense of community that seems to have vanished from other spheres of American life.

“The real conflict for an individual is choosing between a life that is completely self-serving and a life that has some purpose beyond personal gratification and acquisition,” said Michael Josephson of the Josephson Institute of Ethics in Marina del Rey. “Religion has been the traditional expression of that higher ambition, so it should come as no surprise that people are saying: ‘I need a structure. I need to be able to meet with people who think like I do. I need to be in a reinforcing, nurturing setting for that part of my personality.”’

Like many Americans who see themselves as increasingly isolated from their neighbors, the Headleys have found a sense of community in this congregation. It matters to them that their newfound community is, in Price’s words, “values-centered.”

Life’s Quandaries

Price Headley says his return to religion has given him a comforting sense of balance and purpose, offering answers to life’s moral and ethical quandaries. Although he used to scorn panhandlers, for example, he now finds himself hearing Tome’s admonition that “how you spend your money says a lot about you” and is reaching into his pocket a bit more often.

“The spiritual side of me was kind of a void for a while,” he said. “This makes me think I want to evaluate the life I’m living now, as opposed to having some kind of bogus capitulation at the end of my life.”

It also matters to the Headleys that the community they have found shares their young adult sensibilities. On Sunday mornings, there is Starbucks coffee that you can carry into the service, MTV-inspired videos that explore the values people live by and live Christian rock that sounds remarkably like Hootie and the Blowfish. On Sunday and Thursday evenings there are small-group meetings that invite members to investigate the mysteries of faith and the truths of the universe in laid-back settings over pretzels and soft drinks.

There is all this and there is, for those who want it, the ultimate prize: a set of moral guideposts that point the way to goodness--apparent absolutes in a world in which very little seems absolute anymore.

“There is a deep discontent in our society with the breakdown of family, the loss of community and experiences of kinship,” said the Rev. Richard Mowe, president of the Fuller Theological Seminary in Pasadena. “There’s a recognition that schools are not the answer to our deepest problems, that families are not strong enough to deal with all of the issues. Government certainly isn’t going to do anything for us in that regard. So the church is there as a moral teacher in a world in which we’re at a loss to find moral meaning.”

Why, asks Mowe, would tens of thousands of teenagers converge on a stadium in Denver to hear an elderly Pope John Paul II speak? “Part of it may be just wanting a father who speaks with moral authority,” Mowe said. “There’s a yearning there.”

Such a yearning drew the Headleys to a Crossroads service for the first time in April. Now hesitating at the threshold of becoming members of the church, they say that they are exploring their values, their relationships and their society at depths they have never before plumbed.

Religious Revival?

Today, a record 158 million Americans belong to a place of worship, the National Council on Churches says. The figure has risen by roughly 60 million since the start of the 1970s, driven largely by the coming of age of the huge postwar baby-boom generation.

Sociologists debate whether the influx represents a revival of religious fervor. Polls by the Gallup Organization show that the percentages of Americans who belong to churches or attend religious services have remained remarkably stable for decades. At the same time, the Assn. of Statisticians of American Religious Bodies has recorded a significant increase in the percentage of Americans affiliated with a church or synagogue, from 49% in 1971 to 55% in 1990.

One thing is undisputed: The baby boom generation has brought not only more bodies but more fervor and dynamism into places of worship. The boomers’ spiritual journeys have spawned new types of churches and new styles of worship. Their distrust of large organizations, their often-prolonged absence from organized religion and their desire for community are shaping the agendas of a new generation of religious leaders.

Not all members of the baby boom generation are religious dropouts, according to Wade Clark Roof, a sociologist at UC Santa Barbara. Roof has written a book about the tortuous spiritual journeys of the 74 million boomers, who now range in age from 35 to 50.

Roughly 1 in 3, or about 25 million boomers, have continued to worship in the churches and synagogues they grew up in, Roof found. About 1 in 4, or nearly 19 million, dropped out and later returned to organized religion.

He classifies most of the remaining boomers, who number more than 30 million, as either believers-but-not-belongers, who say that they are religious or spiritual but have not gone back to church, or those seeking religious ties whose spiritual quests often lead them to alternative religions.

The return to religion is not just a boomer phenomenon. The same patterns seem to be emerging among members of the post-boomer generation, the so-called “baby busters” from 18 to 34. As they establish themselves socially, financially and professionally, many of these 66 million Americans are retracing their elders’ steps back to churches and temples, often after childhoods in which organized religion played little or no part.

Indeed, no one could be more surprised than the Headleys at their newfound status as churchgoers. In Price Headley’s case, it has been more than a decade since he concluded that the Roman Catholic Church in which he was raised no longer offered anything of relevance to his life.

Kimberlyn Headley’s religious upbringing, in contrast, was nonexistent. Her mother, while in graduate school, set out to write a dissertation proving that God did not exist. Her father, raised by stern Southern Baptists whom she calls “Bible thumpers,” turned away from organized religion altogether.

But early this year, Tom Shepherd, a 33-year-old “elder” at Crossroads Community and a professional acquaintance of Price Headley, shared his excitement about the new church with the Cincinnati couple. Almost immediately, Price Headley says, he and his wife found themselves “connecting” in a way that he never before had associated with organized religion.

“I think of Crossroads as not really like a church because, from growing up, I have this sense of church that I can’t connect with,” he said. “It’s still religious and spiritual. It makes you think about deeper things and deeper purposes. But I don’t really find myself calling it a church.”

Upbringing Spurned

Beyond its sheer numbers and the likelihood that its members have had an extended absence from organized religion, the generation now hunting for churches or temples stands out for another reason: Compared with earlier generations, it has a weak sense of loyalty to the denominations in which it was raised.

George Barna, a researcher based in Oxnard who specializes in church growth, has found that roughly 3 in 4 churchgoing adults under the age of 50 have little or no loyalty to the church of their upbringing. In surveys, those returning to church after an extended absence rarely cite denominational loyalty as a key factor in their choice of churches. Instead, says Barna, they say they choose a church based on the “value” it gives them for their investment of time, for its convenience and for the relationships they have with other members.

According to the National Council of Churches, membership in most mainline Protestant denominations has declined in the last 30 years. It has risen slightly in others but at a slower percentage rate than the U.S. population.

The Roman Catholic Church has fared only somewhat better. Thanks in part to a steady influx of Catholic immigrants, its membership has just kept pace with the nation’s population growth.

Alternatives Thrive

By contrast, many nondenominational churches have experienced steady and in some cases dramatic growth. According to the Rev. John N. Vaughan, publisher of the newsletter Church Growth Today, seven of the 10 fastest-growing Protestant churches are independent of the mainline denominations. (The fastest-growing Protestant church in the nation is the nondenominational Los Angeles Church of Christ.)

About 30% of the nation’s Protestant “mega-churches,” defined as those attracting more than 2,000 congregants each week, are nondenominational. Most did not exist 30 years ago.

For all their accessibility, many nondenominational churches are theologically quite conservative. According to Tome, for example, Crossroads is based on a belief in the literal truth of the Bible, including the creation of the universe in seven days, the virgin birth of Jesus and his rise from the dead.

But most “seekers” are wary of religious doctrine. Indeed, the Headleys, after seven months of church attendance, are struggling with some of the central doctrines of Christian belief, including the virgin birth and resurrection. Heaven and hell are problematic for them.

“The first time I went, I was overwhelmed. They were saying, ‘Jesus, Jesus, Jesus,’ ” recalled Kimberlyn Headley. “Then they started talking about something I felt better with--God.”

Tome says his job is to “touch the hearts” of those without church affiliation and perhaps by doing so to help them toward a life of Christianity. By necessity, his touch is a gentle one. He wears khaki pants and open-collared shirts instead of flowing robes and eschews traditional “thees” and “thous” in favor of plain-English Scripture.

Indeed, the new generation of church leaders, like Tome, tends to avoid references to fire and brimstone, stressing instead shared values and character issues like respect, honesty and compassion.

On a recent Sunday, Tome’s “message” was filled with references to qualities almost anyone could embrace: dignity, reliability, industriousness. His few scriptural references suggested, in plain English, that these common values are qualities that would be pleasing to God.

Rob Lewin, a 38-year-old assistant pastor at Vineyard Community Church in northern Cincinnati, says the technique is a hallmark of new-church efforts to win converts. When prospective members are immersed gently in the Bible, they come to see that the values they hold dear--and which many feel are under attack in today’s society--are the foundation of religious belief as well, he said. That binds them to the Bible and brings them back again and again in search of guidance.

Before they know it, says Lewin, they discover they are Christians.

Moral Guidance

Ultimately, one of the most powerful draws of organized religion is also one of the most obvious: its role as moral helpmate and enforcer.

Religion offers something difficult to find elsewhere to parents who are overwhelmed by the task of raising good children and to young adults still establishing themselves in a morally ambiguous world. It dispenses firm moral guidance, backed up by Scripture and enforced by heavenly authority, that can distill black and white from a society that too often seems painted in shades of gray.

For many who are returning to religion, the perceived needs of children often provide the initial impulse to find a place of worship.

“I don’t know anyone who’s been raised in a church who gets in really big trouble,” said Joe Cione, a 45-year-old father of three who brought his family to Vineyard recently to check out the weekly “celebration.” A once-divorced Catholic who hasn’t attended church in almost 12 years, Cione characterizes American society as “pretty sick.” He thinks that church might help inoculate his children against its effects by instilling in them “a love of themselves, their neighbors, and a lot of guilt--that’s good for you.”

For 39-year-old Kellee Reed and her obstetrician husband, Denny, the desire to introduce their daughters, ages 9 and 3, to religion provided the impetus to begin shopping for a church. Kellee Reed, who grew up attending a Unitarian Church that she now finds too liberal, recalls growing up amid heavy populations of Catholic children and feeling “left out” of a community exposed to common moral teachings.

Although she is still struggling with some of the fundamental tenets of Christian doctrine, Kellee Reed says the messages she has absorbed from recent services at Crossroads “make me reflect on the broader issues of life and how I want my children to see things.”

“I think we could do a great job raising our kids without the church,” said 40-year-old Denny Reed, who grew up with no exposure to religion and for years was repelled by the “dogmatic baggage” that most churches seemed to add to a simple belief in God. “But we can do a much better job with it.”

‘People Have Lost Contact’

For the Reeds too, religion has brought spiritual comfort. Sometimes, said Denny Reed, when a woman on the threshold of motherhood lies on a table bleeding to death, “you’ve got to have something.” In such moments, he said, the quiet belief that God--not a team of doctors--is calling the shots provides more solace than all his years of medical training and clinical experience.

The Reeds also believe that Tome’s gentle Christianity will help them navigate the morally shifting ground of parenthood and, in Denny Reed’s case, of medical practice.

“All of a sudden, you have no sense of what’s right and wrong, and somebody has to say, ‘Hey! That’s wrong!’ ” said Denny Reed. “Part of coming here is to help us with those gray areas.” For the Headleys, the Reeds and the Cione family, the hunt for a church also is a search for a community of like-minded people. Many churches, in turn, are responding to that need with an array of activities, support groups and volunteer opportunities.

Vineyard Community provides a dramatic example. Its 22 pastors, 80 staff members and vast force of volunteers keep the place humming seven days a week with activities ranging from auto maintenance seminars to Bible-study circles. Founded in 1986 with eight members, it now boasts a weekly attendance of 4,000 and ranks among the fastest-growing churches in the nation.

“Churches are in some ways the antidote to the bowling-alone phenomenon,” said Princeton University sociologist Robert Wuthnow, referring to a recent study chronicling the demise of civic membership groups like bowling leagues. “If bowling leagues did it for us in an earlier era, small church groups and other self-help groups are doing it for us now.”

Kimberlyn Headley said she was looking for something within herself when she and her husband started attending Crossroads. But the community they have found there has brought an added blessing, something she believes many Americans want.

“I think people have just lost contact. People don’t seem very happy. They seem very disconnected,” she said.

“That may be the buzz term for the end of the ‘90s: I’m getting connected.”

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.