Report Card Still Out on Creative Homework’s Value

- Share via

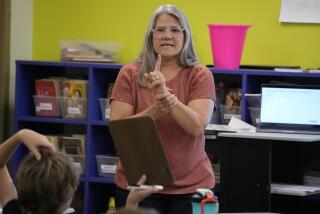

WASHINGTON — Rather than assign her eighth-graders a work sheet of problems on volume and area, Gail Purtell asked them to go home and design a soda can that would use less aluminum.

The Sonoma, Calif., math teacher says she realizes that this type of homework is more difficult, but she and other education reformers believe that it develops a student’s ability to think and solve problems. And it more effectively reinforces what is taught in the classroom.

Over the last decade, learning by rote has given way to more creative lessons in the classroom, an approach now surfacing in homework.

Instead of posing questions about a short story for students to answer at home, a teacher might ask them to compose a new ending. Or they might be told to rewrite a segment of Shakespeare in modern language to prove that they understand its dialogue.

Loveley Billups, director of educational research and dissemination at the American Federation of Teachers, said students need to learn about the presidents, but memorizing their names in sequence is mindless.

She likened it to having to write, “I will not fight on the playground,” 100 times as punishment. “The kid writes ‘I, I, I, I, I’ and ‘will, will, will, will, will.’ By the time they get to ‘playground,’ they don’t even know what the sentence is,” she said.

Purtell said her pupils offer mixed reviews of their new-style homework.

“It’s easier to do pages of work sheets,” she said. “This is a little more of a struggle for students.”

Chandra Bertrand, 13, said the assignment to design a soda can to use less aluminum was fun. “It’s more creative and stuff,” she said. “I’m a creative person, so it’s easier for me.”

(The answer: A shorter, fatter can.)

In some school districts, parents demand more homework. But some parents, such as Silver Spring, Md., mom Marisa Arbona, wonder if the demands of the new system aren’t too much. Her 10-year-old daughter, Raquel, does three times the homework her 15-year-old brother had when he attended the same grade school, Arbona said. She worries that teachers, by zealously pushing the kids to do more, may be “overwhelming the children and the parents.”

On the other hand, teachers in some poor urban areas have stopped assigning homework altogether because students often work after school, care for younger siblings, or deal with family and community problems, said University of Missouri psychology professor Harris Cooper, who for 12 years has researched children’s homework.

Most research and testing indicate that more homework generally produces greater academic achievement. But the U.S. deputy secretary of education, Marshall Smith, cautions that benefits can be offset by weak curricula and poor teaching.

A recent study even questioned whether more homework is ever better.

The Third International Mathematics and Science Study said American teachers assign more homework than Japanese instructors, but the U.S. students did not do as well on tests as their Asian counterparts.

The study said 86% of American teachers assign math homework three to five times a week. In Japan, fewer than one-fourth of the teachers do.

On average, however, Japanese and American students reported spending about the same amount of time studying math and science outside of school.

The study did not conclude why the Japanese did better but said American eighth-grade math classes were not as challenging, few U.S. math teachers are implementing suggested reforms, and U.S. teachers in general receive less practical training and daily support than their Japanese colleagues.

E.D. Hirsch Jr., author of a book on education reform, said that while homework stressing repetitive, or rote, lessons might not benefit high schoolers, it might be appropriate for second-graders.

Memorizing the multiplication tables frees the mind to tackle larger mathematical concepts and problems, he said.

A third-grader in China takes an average of eight-tenths of a second to respond to an addition or subtraction problem, such as 7+6 or 12-4, Hirsch said, and “you can’t get that without a lot of practice.”

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.