Heavy Hand on Chinese Dissent : Movement is all but obliterated, a State Dept. assessment finds

- Share via

The State Department’s annual look at human rights in China reveals a bleak but not surprising picture. The repressive machinery of the state, it says, has effectively silenced all public dissent against the government and the Communist Party, using “intimidation, exile or the imposition of prison terms, administrative detention or house arrest.” By the end of 1996, the survey concludes, “no dissidents were known to be active. . . .” That poignant line could be an epitaph for the briefly bright hope that economic advancement would bring with it greater official tolerance and respect for human values.

Instead, sweeping reforms that have largely washed away the Marxist-Maoist dogma that for decades gripped the world’s most populous country have produced--along with greater prosperity, modernization and widespread official corruption--a deepened determination by the ruling class to hold on to its power. Underpinning the anti-liberalization mood has been the jockeying for advantage among those who hope to gain and those who are fated to lose once the iconic figure of Deng Xiaoping no longer casts its shadow over the political scene. Moderates in China don’t fare well in times of uncertainty and crisis. No one at the leadership level, even if any were so inclined, can afford in the current unsettled climate to appear soft on dissenters. And so the repression that the State Department report describes goes on.

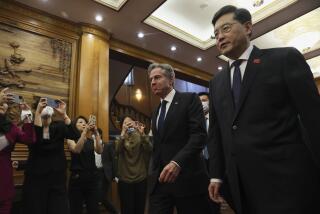

The silencing of dissent in China must not be met by silence among critics of China’s human rights policies. Secretary of State Madeleine Albright has made clear that she will continue to confront China on this issue. She will have a chance to do so soon, when she visits China at the end of this month.

That she has chosen to go to Beijing so early in her tenure is a signal Chinese officials are unlikely to misread. Albright’s message is that China will be a primary U.S. foreign policy interest in the second Clinton administration. The president himself has said that he seeks closer ties with Beijing, with a summit meeting by the end of the year likely. But a warmer relationship depends on eliminating or at least smoothing down points of friction. Among those to be addressed are China’s overseas arms sales, especially of missile technology, bilateral trade issues and, of course, human rights.

Albright believes that the relationship should not be held hostage to any single issue, and she’s right. But neither can an issue like human rights be treated as an inconvenience and expediently ignored. China, says the State Department report, commits widespread human rights abuses “in violation of internationally accepted norms.” Defending those norms defines U.S. foreign policy fully as much as pursuing advantageous trade agreements.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.