Today’s Kids Have the World at Their Fingertips

- Share via

Tired of hearing the hype about the computer revolution? Then listen to Seymour Papert, professor of math and chairman of learning research at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology, who believes the future of the computer revolution has been underestimated by too many “experts” who view today’s primitive models as the final product.

In his recently published “The Connected Family: Bridging the Digital Generation Gap” (Longstreet Press), Papert compares today’s computer revolution to that brought about by the Wright Brothers. How many witnessing the Wrights’ first flight at Kitty Hawk--more of a hop, really--foresaw the subsequent advances in air technology, and their effect on world travel and the very fabric of civilization?

Most of all, Papert argues, computers are changing the very essence of education. Advances in computer technology will revolutionize not just how we work and gather information, but even how we interrelate. The challenge, Papert explained in a phone interview, is to understand the new technology’s implications and to develop organizations to maximize its benefits.

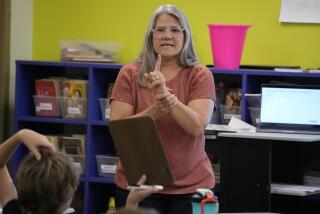

For example, he said, the traditional model of the age-segregated classroom, with a teacher imparting knowledge to students, will increasingly give way to study groups composed of students of all ages. There, students bound by similar interests will learn from one another, exchanging information largely via the Internet, the teacher’s role that of guide.

And a child playing a computerized game in which two characters fight and jump over each other may want to improve his score by mastering his knowledge of jump trajectories. Instead of sitting through “age appropriate” theoretical math classes, then, he may, both through trial and error and his access to the Internet, engage in practical, “just in time” learning.

Similarly, Papert said, “In the real world, building, say, a bridge involves more than just mastering the right mathematical equations. It also involves making plans, writing reports, scheduling, economics and aesthetics, with the best bridges also the most beautiful.” Study groups focusing on such a goal will therefore learn not only math, but also project management, a skill often outside the realm of traditional schooling.

What’s more, because computers are interactive tools, their impact will be substantially greater than that of any other mass media. Thus, “Kids too young to watch TV much can still use a [computer] mouse and make things happen,” said Papert, 68, whose once avant-garde ideas have increasingly garnered acceptance. “And whereas TV just tells kids preconceived stories, computers give them opportunities to do and explore.”

For instance, Papert’s 3-year-old grandson, Ian, recently spent half an hour studying road construction equipment, absorbing via the Internet why, for example, the back wheels of tractors are larger than those in front. This sort of intensive learning in areas of knowledge foreign to Ian’s family has never before been so accessible.

And young Ian is just the front wave of the revolution. “Professional parents have traditionally passed onto their kids specific kinds of knowledge,” Papert said. As computers become ubiquitous, however, this specialized knowledge will also become accessible to just about anyone.

Thus, just as a poor child has access to the same radio and television programming as his middle-class counterpart, he will also have access to the same specialized knowledge. His computer may be older, slower and less powerful, but--critically--it will be on the same roadway accessing the same information.

*

In addition, the primacy of traditional mass media will decline as individuals get their news from the Internet. Thus, John Q. Public will no longer have to sit through a news story that doesn’t interest him to watch one that does. Rather, he will be able to pick and choose his own Internet “newscast,” exploring each story at the desired length and depth. As a result, Papert said, knowledge will become less homogenized, with more people pursuing specialized interests, and the range of knowledge will become broader.

But, he warned, “Society has a bad record of using technology in less than optimal ways,” making it vital that we deepen discussion on how to best use this new tool.

For example, he said, many parents see computers as “glorified baby sitters.” Others won’t allow their children online, effectively isolating them. In place of either extreme, he said, parents need to look at new social models, maintaining responsibility to supervise their children while also allowing them freedom to explore.

Nor are hurried, sometimes oblivious parents the only obstacle: Many educators similarly are blind to the computer’s potential. Some math teachers, he said, use computers as a sort of cyber flashcard, the rough equivalent of using the wires on the Wright Brothers plane as a glorified clothesline.

The misuse of computers may also lead to what he calls the “deskilling of work.” For example, the clerk who presses the “hamburger” and “fries” keys at McDonald’s may allow the computer to do the math without ever mastering the basics himself. Or the assembly line worker may have a computer that effectively does her job for her, without really understanding the process. The individual is thus reduced to an automaton--and becomes the real victim of the computer revolution.

What Papert is saying is at the center of a heated debate, with others arguing strenuously that computers are being overly valued, to the detriment of books. For example, Jeff McQuillan, a lecturer in secondary education at Cal State Fullerton and a critic of the computer revolution, fears that society will leap into the computer age without first mastering the basics of education.

“Access to books is a major determinant of how well people read, and books are still cheaper and more portable than computers,” he said. What is happening, McQuillan said, is that traditional learning materials are being brushed aside before appropriate new forms are ready, especially in poor communities.

Papert believes, however, that public school classes can be computerized--not necessarily with the latest, but with workable equipment--at just 1% of the educational costs per student. The real danger, Papert suggests, lies not in adapting to computers, but in holding on to often stultifying educational and social systems.