UCI Scientist Keeps His Mind on His Work at 80

- Share via

IRVINE — From his modest office at UC Irvine, Dr. Louis Gottschalk maps out his battle plan to save the human brain.

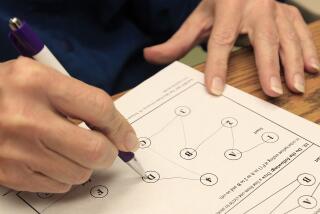

On a recent day, he punched a patient’s speech samples into his computer, which spit out the bad news: a possible brain impairment.

Gottschalk, an internationally known neuroscientist from Corona del Mar, is perfecting a scale that measures “cognitive brain impairment,” or to what degree the brain is malfunctioning. He hopes the scale eventually will be used for early detection of brain maladies such as Alzheimer’s disease. And he’s working on another scale that could be an important tool for employers who want to measure the mental state of job applicants.

Gottschalk, 80, has been studying brain malfunctions for the past 30 years at UC Irvine. His brain scale is the crowning achievement in a career that included counseling soldiers on the front lines in World War II.

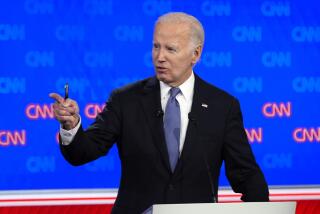

He gained national attention when he concluded that President Ronald Reagan was suffering from cognitive brain impairment as early as 1980--14 years before Reagan was found to have Alzheimer’s disease.

Gannett Co. newspaper publishers had asked Gottschalk to study Reagan’s speech patterns in the ’80 and ’84 presidential debates.

Using his scale, Gottschalk then compared Reagan’s responses to questions with those of then-President Jimmy Carter in 1980 and former Vice President Walter Mondale in 1984. He found distinct signs of cognitive impairment over the four years, such as constant repetition and a tendency to wander off during sentences.

“If you gave Reagan a script to read, he was marvelous. But when you took it away, he was in trouble,” said Gottschalk, the founding chairman of UC Irvine’s psychiatry department.

Rather than go public with his report, Gottschalk decided to hold his findings until 1987, near the end of Reagan’s term, because he feared his study would spark a political battle.

A study from the Alzheimer’s Assn. estimates that 4.1 million Americans are suffering from the disease, which is the fourth most common cause of death in late life. That figure is expected to reach 14 million by 2050 and become the No. 1 cause of death for older adults.

“I believe early detection of the disease is a vital part in the fight to stop Alzheimer’s,” Gottschalk said.

Currently, his scale only measures brain impairments. It cannot tell specifically whether a person is suffering from Alzheimer’s disease, a brain tumor or any other brain-related disease.

Besides the advances in early detection, new drugs are being tested to stop the progression of brain disease. Gottschalk is helping to complete a study of a new drug called Aricept, recently approved by the Food and Drug Administration for patients with mild to moderately severe Alzheimer’s.

“Aricept, in addition to some other drugs we’re testing, seems to arrest the spread of the disease and definitely slows down the pace of dementia,” he said.

Studying brain impairment represents just a fraction of Gottschalk’s research on the human mind. He has been interested in the brain since he was a student at Washington University in St. Louis, where he grew up.

“I always had a curiosity about people and what makes them tick,” he said. “I owe much to my family, where creative thinking was always encouraged.”

After graduating, Gottschalk spent several years as a research psychiatrist in St. Louis, Chicago and Bethesda, Md. In World War II, from his Fort Worth, Texas base, he counseled soldiers who had mental breakdowns when they returned from fighting overseas.

He received his first big teaching break in 1953 as an associate professor at the University of Cincinnati.

In 1967, Warren Bostick, the founding dean of UCI’s College of Medicine, asked him to become the first chairman of the school’s department of psychiatry.

“I was particularly interested with his involvement [in] psychiatric research. He just had great credentials,” said Bostick.

Gottschalk accepted only on the condition that his wife, Helen, would be considered for a job.

“I never move without her,” he said of his wife, a professor of dermatology at UCI who died in 1993.

Along with their four children, they moved to California, which turned out to be a perfect fit.

“I’ve never been in a place that has grown so fast,” Gottschalk said of UCI. “It’s so young, and it has a great opportunity to be something outstanding. It’s going places.”

Since his arrival at Irvine, Gottschalk has been involved in numerous neurological studies. Besides creating his cognitive impairment scale, he refined another scale that measures a person’s mental or emotional level.

Using that scale, Gottschalk would take a five-minute speech sample from a subject, who is told to talk about anything. The sample is then analyzed and scored on a computer by measuring certain variables, such as references to death, anxiety, hostility and depression.

“I don’t think this scale has received the attention in the United States [that] it should,” said Gottschalk, who noted that several countries such as Germany, Australia and Spain have shown much interest.

His determination to aid the human mind is also reflected in his generosity. Gottschalk recently donated $1.5 million to the UCI School of Medicine.

“I couldn’t afford college, but I was lucky enough to get a scholarship. I want to support all these gifted people.”

Despite his age, Gottschalk abounds with the energy of a young man, always opting to take the stairs instead of the elevator.

Although he no longer teaches, he still puts in a full week’s work at his office and sees psychiatric patients.

“I’ve thought about retirement, but I’m addicted to my work. I love it,” said Gottschalk, who has written more than 300 articles and 23 books on mental health.

“The brain is like a muscle. Either you use it or you lose it.”