Acts of Grace

- Share via

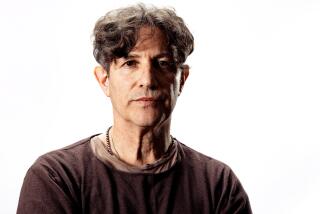

Ingenuity, generosity and loyalty to family and friends have been hallmarks in the life of Dr. El Gendler, who narrowly escaped the Holocaust and then survived the gulag and went on to pioneer safer methods of preparing bone for transplants.

His discoveries have helped limit the spread of diseases such as AIDS and hepatitis--and allowed two young former Siamese twins from his native Lithuania to live relatively normal lives.

Gendler, 73, runs an unusual medical facility in Los Angeles, with his wife, Simona, a research physician he met in Siberia as a young man; and his two sons.

More than a half century ago as a boy of 17, he was uprooted from Lithuania when the Russians arrested his immediate family and shipped them by slow train to Siberia just a week before the 1941 Nazi invasion.

The Gendlers are Jewish. All of their relatives who were not arrested died in the Holocaust.

Strangely, after struggling against extreme privation, the Gendlers ended up prospering in Siberia.

An older brother, Nathan, began a medical practice. El, too, became a doctor in Siberia, also earning a PhD and developing a specialty in bone healing and transplants that allowed him, when he came to America, to establish a tissue bank next to Orthopedic Hospital in Los Angeles.

“Half a million bone transplants are performed in the United States each year, and 1% to 2% of those are ours,” he says proudly.

Six years ago, in a highlight of his life, the Gendlers’ Pacific Coast Tissue Bank donated sterilized bone strips, flexible when wet, that allowed a Dallas surgeon to weave new skulls for separated Siamese twins from Lithuania.

The bone strips, created from femur bones by a process he patented, seemed also to tie the ends of El’s own life together.

Vitalija and Vilija Tamuleviciutes, joined at the head, had been surgically separated by Soviet doctors in 1989, leaving gaping holes in their skulls. Then, in 1991, the girls, by then 3 years old, were brought to Dallas and, in operations performed by surgeon Kenneth E. Salyer, the tissue bank’s bone was used to close their skulls.

The bone, worth about $20,000, has since grown on its own. With further surgical refinements, the girls have developed normally and are now well-adjusted 9-year-olds.

*

The Gendlers’ tissue bank receives most of its bone through notification from the Los Angeles County Coroner’s office that someone who has died had expressed a willingness to donate it. There are 120 to 130 donors a year.

But then careful tests are performed to determine whether the donor had AIDS, hepatitis or any other disqualifying disease or condition.

Since a new AIDS infection is not immediately detectable, all bone that the tissue bank uses is sterilized, with gas penetrating throughout.

“We did a special study and it showed all the virus was killed [by using gas],” the elder Gendler said.

There are many types of tissue banks in the U.S.--some supplying eyes, skin, kidneys, hearts or other organs. Pacific Coast supplies only bone and ligaments for use across the country.

Although tissue banks date from the 1940s, the process of using bone implants began in Russia and Poland a century ago.

But it was only quite recently, about the time the Gendlers’ tissue bank was established in 1986, that it became evident that tissue grafts preserved simply by freezing could transmit diseases like AIDS or hepatitis.

The Gendlers advanced sterilization and sterilization tests that made the transplanted bone much safer.

As a doctor in the Soviet Union, until he came to the U.S. in 1980, El Gendler had studied for many years to learn why the healing of bone in a patient’s body is so slow and labor-intensive at the cellular level.

He found that bone that has been merely frozen not only can remain contaminated, but tends to be rejected by the body because it introduces antigens, which interrupt healing.

Sterilization and other biochemical treatments can much reduce these problems.

*

It was a major leap of faith for Gendler to bring his family to America, knowing that it would be difficult to establish all their medical credentials here. They arrived with only $90 in cash and the sponsorship of the uncle who was by that time 92 years old.

But it has worked out well.

“California is a paradise,” Gendler observes. “In Siberia, you have to stand three or four hours to buy a chicken. Maybe the chicken will die, and then they sell it.

“I will never go back. My whole life, I wanted to leave the Soviet Union.”

Of course, when Gendler was growing up, the son of a well-to-do businessman, Lithuania was an independent country. Stalin annexed it in 1940.

Ross Stein, a scientist with the U.S. Geological Survey who is married to Gendler’s niece, calls Gendler’s subsequent life story “amazing, horrendous and inspiring.”

Just surviving after the family’s arrest on uncertain charges was an achievement. Thrown into cattle cars with 80 other families, including not only Jews but many of Lithuania’s civil and military leadership, many died during the six-week journey, with many stops on sidings, to a Siberian prison camp.

It was the same Narim district in central Siberia where Stalin had been exiled before the Russian Revolution.

Fortunately for the Gendlers, a relative had sneaked in extra food for them.

But at the end of the journey, the authorities separated Gendler’s father from the rest of the family and they did not see him again for several years.

In the gulag during the war, “all we got was 500 grams of bread a day,” Gendler recalls. “Many people died the first winter, but in the spring we planted potatoes. The local people were very nice, and with the bread and potatoes we survived.”

Gendler was able to make himself useful in prison and later in what was known as exile, confinement far from the country’s European urban centers.

When a telephone station, just a single phone, was installed near their camp, for example, and it went on the blink, Gendler pretended to be a telephone technician and offered to fix it.

He says now that he hadn’t a clue how phones worked. He opened the microphone cover and all of the contents fell on the floor. Most of the carbon granules disappeared under the floorboards.

In a panic, he put the microphone and the granules he could scrape up back in the receiver and screwed the phone together, turned the crank and spoke into the receiver. To his amazement, he got an answer.

Years later, “I understood the miracle,” he says. “There had been too many carbon granules in the microphone and they kept the diaphragm from vibrating, so when I could only put a few back, the diaphragm was freed to move.”

The feat won him easier prison work.

After the war, escaping from the camp and making his way to Tomsk, he found jobs and managed to enroll for a medical degree.

When, after six years, the KGB caught up with him, he was within four months of earning the degree, and he convinced his captors he would be more use in the prison as a doctor, if they would only let him finish his studies.

Just after his graduation, however, Stalin died, and things began to change. Although he had to report to the authorities until 1958, he was able to stay in Tomsk with his wife and children.

Practicing medicine and working on bone grafts, he developed a method to use powdered bone to fashion bone implants that would fuse to the missing or broken bones of patients.

Learning from his mother of an uncle who had emigrated to Los Angeles many years before and had become successful in real estate, Gendler wrote to him and received an invitation to come to California.

But it took 12 years to get a visa to go. When he first applied for it in 1968, the KGB denied it on the basis that he knew state secrets.

“What secrets?” Gendler asked.

“See,” one young officer replied, “You won’t tell us.”

In 1980, the visas were finally issued.

It was Tillman M. Moore, a lead doctor at Orthopedic Hospital and USC Medical School professor, who recognized Gendler’s talents and finally joined with him and other members of the family in forming the tissue bank. He and Gendler became its medical directors.

“He’s a genius in this whole field, innovative and open-minded,” Moore said recently. “He has a very motivated ego of course, but he also has a very altruistic way of operating.”