One Family’s New Life Cost a Tragic Toll

- Share via

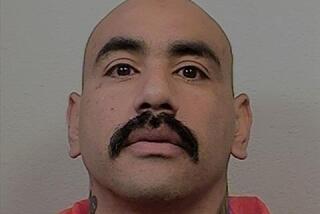

SANTA ANA — Every Saturday morning, Ramon Guillen, who left Granjenal 11 years ago at the age of 12, weeds, waters and cleans the graves of two younger brothers at Holy Sepulcher Cemetery.

His brothers, Rolando and Leonardo, were gunned down on Santa Ana streets in 1994 and 1995, during the height of gang violence in the city. A cousin, also killed by gang members, is buried nearby.

“I tried to talk to them,” he said of his brothers, “but it’s impossible to change someone if they don’t want to listen.

“When I was in the gang, many people came to talk to me, from the church, from my family. It didn’t do any good. If you don’t live it [the gang life], you don’t understand.”

For fellow immigrants from the small Mexican farming village, the three teenage victims are the most jarring casualties of the new life in Santa Ana and symbolize all that is frightening about American culture.

Even Ramon, who was a gang leader but quit after he married five years ago, believes his brothers would be alive if the family had stayed in Granjenal.

“We wouldn’t have had these kinds of problems because they didn’t exist,” he said. “Everything that happened to me, to my brothers, it happened because we came here.”

Nearly everyone from Granjenal knows the tragic story of the Guillen family. When reminded of it, most shake their heads, say a silent prayer and point out how different this brood is from the norm.

For a start, Ramon and his nine siblings were left impoverished and fatherless in their hometown in 1986 when Ramon Sr. died of a heart attack at 36 in Santa Ana as he dressed for another day of construction work.

With few options in Granjenal, his widow, Imelda, came north. With the help of relatives in Tijuana and smugglers, she managed to get nine of her children to Santa Ana before running across the border with Ramon at her side.

The family moved temporarily into a brother’s garage--the first of six Santa Ana homes in 10 years. Hounded by bill collectors, fearful of crime and gangs, the Guillens always seemed to be on the run.

The children did poorly in school--none has graduated high school and all but the youngest three struggle with English. Unlike many Granjenal immigrants of their generation, Ramon and his siblings remain illegal immigrants, with marriage to a citizen or legal resident their only chance of gaining legitimate status.

Ramon remembers his first months in Santa Ana as overwhelmingly sad. He missed the open air and the farm animals of Granjenal. One night, he packed his few belongings and circled the city on foot, trying to find his way back to Mexico. An uncle brought him home.

He learned to hide his vulnerability behind a tough armor, and within three years, Ramon had helped start the Second Street clique of the Lopers, a gang primarily of immigrants from Mexico.

He carried a gun and was shot twice; he will carry the scars on his forearm and lower back forever.

Ramon quit the gang after his marriage to his grade-school sweetheart from Granjenal. “I didn’t want something to happen to me. I had to take care of my family,” he said. He could not, however, convince his younger brothers to do the same.

Rolando, 19, was shot as he rode a bicycle down an alley with a friend. Family members say he crawled under a car for cover before being shot a final time in the head.

A year later, Leonardo blew a kiss to his mother and left the family’s apartment to visit his pregnant girlfriend. Shots sounded a minute later, cutting down Leonardo in the courtyard. He was 16.

In those two years, 90 young men were killed in Santa Ana gang shootings. Many belonged to the Lopers.

Ramon and his wife now have three children. Like hundreds of men from Granjenal, he is a member of the Laborers Union, and he reports there every morning at 6 hoping for work. Through his wife, a legal resident soon to become a U.S. citizen, he too is close to obtaining legal residency.

At 23, he is a battle-scarred survivor whose weekends are spent with family, including his two dead brothers.

The ritual at the graveyard assuages some of the guilt Ramon carries. He tunes a portable radio to a station that plays Banda music. He digs a neat line in the grass around the graves with a trowel, polishes the flat marble headstone and arranges a border of red silk flowers, making the site the most colorful around.

When he is finished, he drives a mile to a line of sycamore trees and spends a few minutes listening to the wind rustle the leaves. If he closes his eyes, he can almost believe he is back in Granjenal.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.