Bad Winters Suggest Arctic Ozone May Recover Slowly

- Share via

Ozone recovery over the Northern Hemisphere may take longer than expected if recent winters are any indication, an analysis by European scientists concludes.

The European researchers used weather balloons to measure ozone concentrations over the Northern Hemisphere during the winter of 1995-96. Arctic ozone reached record lows that year, dipping at some points to 64% of normal levels.

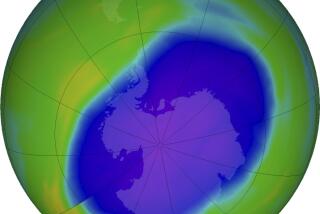

Ozone is critical to life on Earth because it blocks the sun’s ultraviolet rays, which can have effects ranging from sunburn to cancer. Scientists became alarmed when they discovered in the 1980s that ozone completely disappears over parts of Antarctica each October. They also found annual ozone thinning over the Northern Hemisphere.

Atmospheric chemists traced the ozone depletion to chemical destruction by chlorofluorocarbons used in air conditioners, aerosol sprays and other products. An international treaty subsequently banned the chemicals, and ozone is expected to begin recovering soon.

If all goes well, scientists say, the ozone problem should be fixed by the middle of the next century. But the recovery of northern ozone may be delayed a few years by extremely cold weather in the stratosphere, the atmospheric layer that contains the ozone.

Extended cold weather in the northern stratosphere creates ideal conditions for ozone depletion, the European researchers found in their 1995-96 research. And lately the stratosphere seems to be staying cold longer than it used to.

“What has been peculiar about the past few winters is that the Arctic stratosphere has stayed cold for longer than average,” NASA scientist Richard Stolarski wrote in a commentary accompanying the European research, which was published in the British journal Nature.

Colder stratospheric temperatures are one result of global warming, said Markus Rex, the Nature paper’s lead author and a researcher at the Alfred Wegener Institute for Polar and Marine Research in Germany.

“When a larger fraction of the heat radiation from the Earth’s surface is absorbed in the lower parts of the atmosphere, smaller amounts reach the stratosphere,” he said in an e-mail message.

The stratospheric cooling trend may also be a result of ozone loss because ozone absorbs sunlight, warming the stratosphere.

Either way, the result could be a Northern Hemisphere ozone hole similar to the one that forms over the Antarctic each year, even though the atmospheric concentration of ozone-destroying chlorofluorocarbons will peak in the next few years.

“If temperatures should get only slightly colder than they were in the winter of 1995-96, a complete destruction of ozone in some altitude regions seems to be possible,” Rex said.