300 Million Miles to Mars--and Now Things Get Tough

- Share via

As the Pathfinder spacecraft prepares to take its wild ride through the pink Martian skies Friday toward a landing on the Red Planet, engineers at the Jet Propulsion Laboratory in Pasadena have plenty to worry about, they made clear at a news conference Tuesday.

To begin with, the tiny probe has to slide into the Martian atmosphere at a precise 14-degree slope, lest it skip into space like a stone on water or descend too steeply and overheat.

Then, in sequence, it has to:

* Deploy a series of braking moves more complex than any Rube Goldberg device, including parachutes, rockets and air bags--all with clockwork precision.

* Bounce sky-high without bursting an air bag and then roll to a halt without damaging the delicate rover inside.

* Roll to a rest in a flat spot where Pathfinder’s petals can open freely, then flip itself into an upright position and roll out the spring-loaded runway for the rover.

After that, a camera mounted on a mast like a periscope has to look around and find the sun, then calculate which way the Earth lies to send its first images. It must make sure the air bags aren’t blocking the path for the rover’s descent onto the Martian soil.

Only after all this happens flawlessly can the foot-high robotic geologist named Sojourner begin its six-wheel exploration of Mars, looking for signs that water--and perhaps life--once populated this now dry and apparently barren world.

Despite the hazards of the descent, “The most uncertain period we have is once we land,” said mission manager Robert Cook, explaining that they might have to improvise at the last minute, depending on conditions on the surface.

So far, NASA’s bargain-basement probe has been performing “fantastically,” said Deputy Project Manager Brian Muirhead, who last Thursday had the pleasure of flipping the switch that started the landing sequence. “It was a personal milestone for me,” he said. His colleagues called him out of a meeting to push the DO EDL (Entry, Descent and Landing) button.

And while the threat of a dust storm stirred up some concern earlier in the day, the storm appeared to be rather small, more than 600 miles away and not moving toward the landing area. Even so, Martian dust is so fine that even a substantial storm wouldn’t pose much more of a visual obstacle than normal Los Angeles smog on a summer day, said project scientist Matthew Golombek.

Pathfinder hasn’t been called on to do much except coast through space since its launch seven months ago. But now that it’s a mere 800,000 miles or so from Mars--having traveled more than 300 million miles from Earth--the anticipation at JPL is clearly building.

Muirhead used the pre-landing press briefing to review the precarious approach. As he illustrated in an animated simulation, when the $171-million probe nears Mars it will jettison its circular “cruise stage” containing the fuel and stabilizers that got it that far. As the craft burns through Mars’ carbon dioxide atmosphere, its heat shield glowing bright red at 10,000 degrees, the spacecraft will begin to wobble like a top.

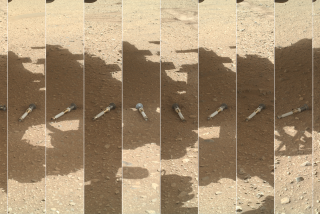

With clockwork precision, the shield drops off, a parachute pops out at twice the speed of sound, the landing craft gets lowered on a long cable and radar beams shoot out from under the craft to sense the ground. In fractions of a second, air bags inflate and rockets fire for the landing.

This is where things really get tense, according to Cook. The air bags have to be rolled in on winches and somehow tucked underneath the craft so they won’t be in the way. It’ll be hours after the 10 a.m. landing before engineers on the ground know whether everything has worked as planned.

Assuming it has, the robot will begin to “scurry around in the field” and look for interesting rocks. At the same time, a stereo camera mounted on the mast will take panoramic pictures of the Martian landscape in 12 colors.

The first images of Mars are scheduled to be transmitted back to Earth about 6:30 p.m. Friday.

The spacecraft is set to land in an ancient Martian plain created during a flood of truly Biblical proportions, when as much water as is held in all the Great Lakes combined emptied in a period of two weeks, carrying a “smorgasbord” of Martian geology with it, Golombek said.

“All in all, it looks like a very nice place to touch down,” he said.

If things go wrong, at least NASA scientists have the consolation of knowing that this mission is only one of 10 small spacecraft headed to Mars over the next 10 years.

“If it fails, others will pick up where it leaves off,” said project manager Tony Spear. Of course, he said, “We will be bummed out, to say the least.”