Reforms Seen as Key to Asia’s Fiscal Recovery

- Share via

Just a few months ago, the 21st century still seemed certain to be the Asian Century--an era in which Western dominance of the global economy would be surpassed by Asia’s mighty industrial engine and burgeoning wealth.

Today, devastated by collapsed currencies and stock markets, their banking systems emasculated and their people’s confidence deeply shaken, the eve of the 21st century finds the nations of East Asia facing perhaps their greatest challenge of the post-World War II era.

It is a mammoth challenge for the rest of the world as well. With a third of the planet’s population and a similar share of its industrial capacity, the path East Asia follows in its drive to recover its economic health--or in China’s case, to maintain it--will invariably alter the landscape of the global economy.

Some experts believe that the future of world capitalism itself is at stake. After two decades of tremendous growth and rising incomes, much of East Asia has been made poor again by this financial crisis.

The temptation to walk away from the tenets of international trade and cooperation, a major global triumph of the 1990s, could become overwhelming--and if nations succumbed to this temptation, there would be dramatic, if hard to predict, implications for every country.

Millions of trade-related jobs could be at risk; competitive price deflation could ravage many companies--or protectionist fever could limit the availability of goods, sparking inflation; the decade’s roaring stock bull markets could reverse amid plunging confidence; and political instability could become the global norm.

For now, global financial authorities are trying to extinguish the most dangerous fire: the spreading doubts about Asia’s banking system, which, like all banking systems, requires confidence above all else to survive.

When that situation is stabilized, East Asia’s focus will turn again to the future. That is when the battle lines will be drawn.

Many Western analysts fear that Japan, South Korea, Malaysia and other states in the region will simply attempt to export their way back to wealth--a flood-the-market strategy that could raise simmering protectionist sentiments around the world by threatening other nations’ jobs.

The Japanese yen has already slumped to nearly 128 per U.S. dollar, the weakest level in five years, guaranteeing new pricing pressures on U.S. companies from ever-cheaper Japanese imports.

For Thailand and Indonesia, their pricing advantage over U.S. competitors has ballooned by more than one-third as their currencies have plunged, while their ability to afford U.S. goods has declined by a like amount.

The United States, while resigned to the reality of this new currency disadvantage, has cautioned Japan, in particular, about merely focusing on exporting more. Instead, the Clinton administration is insisting that East Asia change from within.

The U.S. prescription for the region: abandon the once-celebrated economic model of heavy government-directed investment, which encouraged cronyism and massive corporate borrowing for industrial and real estate projects that had poor profit prospects; open these economies, and let free markets rule via “Darwinian capitalism”; encourage domestic consumption.

If East Asia can change, it can prosper, many analysts insist.

“This crisis is a result of delays about reform of finance and markets in the region, but the fundamental reality is that the key factors of global production have shifted to the Pacific countries,” said Stephen J. Anderson, visiting professor at Temple University in Tokyo.

“These countries still have enormous potential,” said Russell Jones, chief economist at Lehman Bros. Japan Inc. “It’s hard to imagine that once they get through this phase they won’t be growing at much faster rates than the [West] can. But they can’t operate outside the rules the rest of the world has to play by.”

Idea of Economic ‘Miracle’ Rejected

Although the focus in recent weeks has been on all that has gone wrong in East Asia, experts caution Westerners against inferring from these woes that the region’s spectacular economic performance over the past few decades has been a sham.

Indonesian President Suharto, who has ruled since 1967, inherited a country that lived in the economic dark ages.

Although Suharto has magnificently enriched himself and his family in Indonesia’s boom, he also lifted all but 25 million of the country’s 200 million people above the poverty line, thanks to heavy investment in education, health care and rural development.

What’s more, the positives that helped fuel strong growth in much of East Asia in the 1990s are still there: an extremely young population, high literacy rates, high savings rates and a modern export sector.

Still, many Western analysts have come to reject the popular idea that East Asia’s long growth boom constituted an economic “miracle.”

The increasingly prevalent view is that the region was simply well-positioned over the past decade as Japan directed investment away from its high-cost economy and as many U.S. companies were engaged in a restructuring frenzy, dropping low-return businesses.

That allowed East Asia to use its large labor force and access to money to engage in massive industrial and real estate development--the establishment of which, by itself, was the main driver of the region’s rapid economic growth.

“Perspiration, not inspiration,” is how U.S. economist Paul Krugman describes the Asian “miracle.”

Merely creating the capacity to produce, however, does not guarantee long-term success. What is paramount is the return earned on that capacity investment.

The Western view now is that East Asia’s financial system lacked the discipline imposed by truly free markets, where steely-eyed investors demand a decent return on their money.

Instead, critics say, East Asian banks that were closely tied to national governments through political cronyism financed far too many projects that, while creating jobs, had poor economic fundamentals or were outright symbols of national vanity--such as Malaysia’s 110-story Petronas Towers.

“The problem is not that they [Asia] saved too much but that they invested too much of that savings in capacity that wasn’t wanted at this stage of the world economic cycle,” said G. Paul Matthews, head of San Francisco-based money manager Matthews International.

As countries such as Thailand, Malaysia and the Philippines were churning out clothing, shoes, toys, consumer electronics and other lower-end goods in recent years, China too was building capacity, creating a major export force in direct competition with its much smaller neighbors--and eating into their companies’ profit margins.

Meanwhile, South Korea, far ahead of many of its neighbors, was adding more production capacity in higher-end goods, such as autos, steel and semiconductors. But these sectors too were facing increasing competition from other countries’ producers.

In addition, South Korea faced heavy union pressure for higher wages.

“Wages have been increasing much faster than productivity,” said Sagong Il, president of the Institute for Global Economics in Seoul. “At the company level too they were more interested in quantitative growth than qualitative adjustment,” or productivity gains.

Recipe for Disaster Written by Mexico

The first sign of stress in East Asia was a marked slowdown in export growth, beginning in 1995.

By 1996, Asian countries that once had financing surpluses with the rest of the world began to run deficits.

The recipe for disaster was written by Mexico in 1994: In a small economy, soaring debts coupled with slowing economic growth can send investors and creditors fleeing in fear, which then can make a currency collapse inevitable.

Thailand surrendered on July 2, allowing its currency, the baht, to plummet in value versus the dollar and Japanese yen. That triggered devaluations throughout the region, in turn collapsing stock and real estate markets and fully exposing the high debt levels that many companies had incurred in the boom years.

For Japan, which has endured seven years of mostly near-recession conditions in the wake of its stock market and real estate collapses of 1990-91, the East Asian debacle similarly forced a showdown between market forces and the country’s badly weakened financial system, which has lent heavily to the region.

That has culminated in the unprecedented failures of two major banks and Japan’s fourth-largest brokerage over the past two weeks.

In the West, the Japanese government’s willingness to allow those institutions to fail, while protecting depositors, has been hailed as a seminal event: Finally, Japan has admitted that its deadwood must be pruned for the tree to grow again.

In like fashion, the International Monetary Fund, in supplying emergency loans to Thailand and Indonesia to keep their banking systems from melting down, is demanding that the countries close down sick lending institutions and open their economies to greater foreign competition--the idea being that only free-market forces can rid an economy of inefficiencies and promote new growth.

But will East Asian governments so willingly give up the control they have exerted over their economies since World War II?

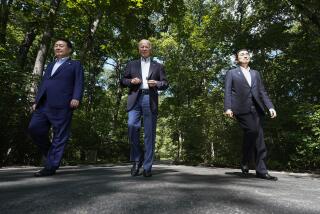

At the Asia-Pacific Economic Cooperation (APEC) summit last week, Mexico’s President Ernesto Zedillo told his Asian peers that they had little choice. Take the tough medicine that Mexico did in 1995, Zedillo said, and your economies will come back strong.

That medicine includes shutting down insolvent banks, paring government spending and creating greater transparency in the way government and business operate, Zedillo said.

In the hours after the meeting, leader after leader went to the podium to say they were ready to follow Zedillo’s advice. But that was the easy part. Every leader in APEC, including President Clinton, returned home to an audience that is increasingly skeptical of the claim that free trade and open markets lift all boats.

The human toll claimed by Asia’s economic reversal is already climbing fast: Interest rates have rocketed as credit has become scarce; stock markets have crashed; and layoffs have begun at employers large and small as economic growth has slowed.

With elections looming in South Korea, Indonesia and the Philippines, governments risk the wrath of angry voters whose purchasing power has been slashed and whose job prospects are dwindling.

Temptation to Protect Domestic Economies

For East Asia, the great temptation is obvious: Protect your domestic economy as much as possible while ramping up your export machine to sell anything and everything to the rest of the world at cut-rate prices.

In part because of IMF conditions imposed on countries seeking aid, keeping East Asian markets open to foreign competition will become increasingly difficult--even though many analysts agree that reforming the domestic sector of these economies is paramount for the region in the long run.

“In many of these countries, the domestic economy is much less efficient than the export economy,” said Michael Boskin, economist at Stanford University.

Yet, in Thailand, the government has raised the value-added tax from 7% to 10%, discouraging retail sales, while imposing higher taxes and duties on many imported goods--including fully assembled vehicles.

In Thailand and Malaysia, campaigns have been launched to promote buying local goods over foreign goods. “Eat Thai, Use Thai, Buy Thai, Travel Thai and Help Economize” is the government mantra of the moment.

Malaysia is urging its people to examine every aspect of their lives for ways to save and keep money in the country.

At the same time, East Asian exporters will undoubtedly be betting that other markets, especially the United States, will remain wide open to their goods, providing needed hard currency for rebuilding.

Clinton, at APEC, offered up a solution for restoring Asia’s growth: Japan would spur its domestic economy and become the region’s new “locomotive.”

But Japan politely declined.

“We are certainly not arrogant enough to think that we can take the role of the locomotive for Asia,” Prime Minister Ryutaro Hashimoto was quoted as saying.

Clinton’s plea was, of course, grounded in the American experience.

“America’s leadership [in the postwar period] came less from its nuclear umbrella and more from its markets,” argued Merrill Lynch economist Ronald Bevacqua.

America’s Cold War allies got to be part of the U.S.-centered trading system, a powerful incentive to join the Yankee team.

“Japan can provide all the financing it wants, but you provide more leadership and have more power when you provide a market,” Bevacqua said.

But that is not happening. In 1996, Japan ran bilateral trade surpluses with Thailand, Malaysia and South Korea. And with the latest economic data indicating that Japanese economic growth is at a standstill, there is little reason for Asian exporters to look to Tokyo for help.

“It’s easy to say Japan should buy more products from Korea, instead of just loaning them money,” said Chang Yi, an analyst at Kokusai Securities Co.

It is easy to say, but it is almost impossible, because there is little demand for many Korean products in Japan, he said.

U.S., Europe Prime Targets for Exports

That leaves the United States and Europe as prime targets for a new wave of inexpensive Asian exports.

While imports only account for about 12% of U.S. gross domestic product, and imports from Asia are one-third of that total, many economists worry that the outcry from U.S. companies and labor unions hurt by cheaper imports will exact a political toll in 1998.

“We are in an environment in which, even with low unemployment, we have surprisingly high protectionist sentiment in this country,” said Boskin--noting that Congress last month refused to give Clinton the “fast-track” trade treaty power he fought hard to get.

What’s more, many U.S. companies may be drawn to move more manufacturing to Asian countries, with the sharp decline in labor costs stemming from the currency devaluations.

Of course, world currencies have swung wildly for decades, and competitive advantages among nations are constantly shifting. But what makes this situation different is its scale, given East Asia’s huge population and industrial wherewithal.

In addition, what if China decides to devalue its currency, raising the ante with its regional competitors? What if U.S. pressures on Japan and the rest of East Asia to open their economies trigger retaliatory selling of the hundreds of billions of dollars worth of U.S. Treasury securities owned by those countries?

Perhaps most worrisome is the potential for political and economic backlash should East Asia discover that there simply may not be a market for much of what it would like to sell, regardless of price.

“The U.S. cannot physically import what Asia needs to export,” Bevacqua said.

“I think there is hardly a route out of this for many of these countries” that have excess capacity in low-end manufacturing and yet burgeoning populations in need of jobs, said a pessimistic Edward Leamer, economics professor at UCLA. “The euphoria of the 1990s is going to turn into [worker] depression and dissatisfaction with the economic system if it doesn’t deliver.”

But that view implies that global capitalism may have reached its zenith--an idea many economists reject.

The United States, analysts note, went through wrenching economic change in the 1990s, but today is vastly more prosperous because of it.

The optimistic view is that, with East Asian reforms that encourage domestic consumption over pure export, more efficient markets and revitalized banking systems, there is no reason why the 21st century shouldn’t be the Asian Century after all--presenting both greater challenge and greater opportunity for the United States.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.