Mars Keeps Looking More Like Earth

- Share via

As they waited to hear from the Pathfinder spacecraft--unable to send data from Mars for the last 10 days--scientists at the Jet Propulsion Laboratory reported Wednesday that the Red Planet is not “just a big ball of rock” but has a clearly layered internal structure, much like the Earth.

Meanwhile, the rover Sojourner waits silently at some unknown location on Mars for instructions from its mother ship.

The layered structure, along with new close-ups of pebbled and pockmarked rocks, adds weight to previous evidence that ancient Mars was a warm, wet planet capable of supporting life.

“This is the first evidence that Mars has a core, mantle and crust,” said project scientist Matthew Golombek.

At the same time, the pebble-encrusted rocks suggest that “water was stable on the surface. As you know, that is the one requirement for life,” he said. Both findings imply that early Mars was hotter and more geologically active than previously thought.

The presence of a distinct core--probably of iron, like the Earth’s--was deduced from subtle changes in the planet’s spin picked up by shifting radio signals beamed between Mars and Earth. The way the planet spins changes depending on how the mass inside is distributed--just as an ice skater spins slower with outstretched arms. The unseen internal structure also affects the turning of the planet around its axis, said JPL scientist William Folkner.

Further measurements should reveal whether any part of the core is molten, like Earth’s. Only a spinning liquid metal core, scientists believe, can churn up the electric currents necessary to produce global magnetic fields.

Meanwhile, close-ups taken by the rover’s stereo cameras before the communications breakdown show clear signs that some rocks are conglomerates of smaller pebbles, fused over time. The roundish shapes of the pebbles suggest that they were carried by flowing water for long periods, losing their rough edges along the way. Pockmarks, or “sockets,” in the rocks appear to be holes where pebbles have been dislodged, said rover scientist Henry Moore of the U.S. Geological Survey in Menlo Park, Calif.

However, the “problem of the pebbles,” as Moore called it, is far from solved. They could have been rounded during a flood, he said, or formed from melted glass thrown into the air during a fiery meteor impact, cooling into globules as they hit the ground. They could even be splatters from ancient volcanoes.

“It’s going to take a long time to figure out what we’ve seen,” he said. “[But] I think we’re looking at conglomerates.”

Another martian mystery--concerning the possible presence of sand--is a clear source of disagreement between Moore and another Pathfinder scientist, Wes Ward of the Geological Survey in Flagstaff, Ariz. Ward said Pathfinder had solved a puzzle left over from Viking missions 20 years ago. Viking orbiters saw clear signs of sand dunes, but once the mission’s landers reached the surface, they found only floury dust, too fine to form dunes.

However, when Sojourner scrambled over a hill and looked down into a valley, it saw details of dunes that looked much like sand dunes on Earth, with rising slopes on the windward side, a sharp crest and a steep slope on the trailing edge. These dunes are “markedly different” from those Viking saw, Ward said, and are clear evidence of sand.

Moore, however, is not convinced that the dunes are made of sand and thinks they might consist of small clods of finer dust, or “virtual sand.” The size of the grains is significant, because sand-size particles probably would have required water to break them down from rocks. Finer dust particles tend to be created by other chemical processes.

Pathfinder also reported the first signs that fall is approaching on Mars, and dust storms are expected within the next few weeks. “It’s starting to get cold,” Golombek said.

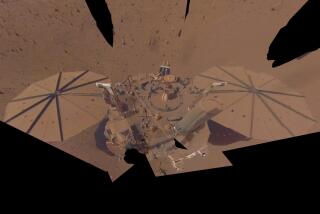

Since Pathfinder’s spectacular parachute landing July 4, the spacecraft has long outlived what was supposed to be a one-week mission for the rover and one month’s service for the lander. Now into its third month, the mission is switching gears to a completely solar-powered mode. It appears that a waning battery on the lander is behind the communications problems, according to acting flight director Jennifer Harris.

However, engineers have not yet pinned down the difficulty. “We still do not know what situation we’re in,” Harris said.

Just before Pathfinder stopped transmitting scientific data, Sojourner had left a cluster of stones called the “rock garden” to move to a large rock named Chimp, about 30 feet from the lander. The rover was programmed to head back for Pathfinder if it didn’t hear any commands for six days.

“It’s not known where she [Sojourner] is right now,” Moore said. “If she behaved herself, she would be back at the lander. . . . She’s patiently waiting for Jennifer [Harris] and her crew to bring back the lander [into communication] so she can send back more information.”

Golombek expects that to happen soon. “[Pathfinder] is not dead in any way, shape or form,” he said. “I hope to have this job for a year.”

(BEGIN TEXT OF INFOBOX / INFOGRAPHIC)

Of Cores and Sockets

Scientists from the Mars Pathfinder project said Wednesday that:

* The Red Planet has a layered structure, much like Earth.

* Closeup photos taken by the rover before a recent communications breakdown show signs that some martian rocks consist of smaller pebbles cemented together over time. The pebbles’ roundish shapes suggest that they were carried by flowing water, and pockmarks, or sockets, in the rocks appear to be places where pebbles were dislogded.

Subtle changes in spin were picked up by shifting radio signals between Mars and Earth.

Source: NASA’s Jet Propulsion Laboratory, Pasadena.