Medicine’s Magic Bullet Is Under Siege

- Share via

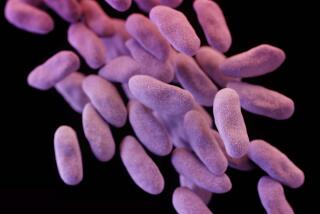

A report last month that a Michigan man was infected by staphylococcus bacteria resistant to the most powerful antibiotic approved for use, vancomycin, triggered only fleeting news coverage. That case and a similar one in New Jersey reported Thursday should send shudders though the medical community and the public. If those bacteria spread--as have many other pathogens resistant to antibiotics--the most deadly type of hospital-acquired infection will become untreatable.

At the turn of the century, bacterial diseases were the leading causes of death in the United States. But advances in public health and the discovery of antibiotics largely vanquished them. In 1900, pneumonia and tuberculosis caused almost one-quarter of all deaths in the U.S. By 1990, those two illnesses caused less than 4% of all deaths.

When people are infected by antibiotic-resistant bacteria, their illnesses are more deadly and more expensive to treat. It costs 15 times more to treat a patient with resistant tuberculosis than with ordinary tuberculosis. Nationwide, illnesses caused by antibiotic-resistant bacteria are estimated to cost at least $4 billion annually.

Despite the extraordinary value of antibiotics, the overuse of these miracle drugs in medicine and agriculture endangers their continued effectiveness. The more antibiotics we use, the more likely it is that bacteria will develop mechanisms to evade them. For example, before 1987, antibiotic resistance was uncommon in Streptococcus pneumoniae, a bacterium that causes pneumonia and bloodstream and ear infections. Now as many as 40% of S. pneumoniae strains are resistant to antibiotics.

One major cause of excessive use of antibiotics is that when people go to doctors, they expect a cure. And doctors all too often comply by immediately prescribing antibiotics, without determining if antibiotics will cure the illness.

As many as half of all outpatient antibiotic prescriptions are inappropriate, according to the U.S. Office of Technology Assessment. The drugs are commonly prescribed to treat colds and flu--both are caused by viruses, which are unaffected by antibiotics. Unnecessary prescriptions are worse than wasteful, because they facilitate the proliferation of antibiotic-resistant bacteria.

Another problem is that physicians often prescribe the strongest, newest, broad-spectrum antibiotic, rather than taking a culture to determine if an older antibiotic would suffice. Broad-spectrum antibiotics kill a wide range of bacteria. But using the most potent antibiotics when others would do the job jeopardizes the future value of the newest ones.

While medical use of antibiotics is the main culprit, their use in livestock also fosters the spread of antibiotic-resistant superbugs. In the 1940s, researchers discovered that chickens grew faster if small amounts of antibiotics were added to their feed. Since then, almost half of all antibiotics sold in this country have been added to feed or water given to poultry, cattle, pigs and fish to speed growth and cut costs. Farmers can buy such antibiotics as penicillin, tetracycline and erythromycin over the counter, without any supervision by a veterinarian. Infectious disease experts have long warned of the dangers of routinely using antibiotics in livestock feed, but agribusiness has fought off appropriate safeguards.

Until recently, every time we squandered an antibiotic there was another magic bullet on the pharmacist’s shelf. But now the shelf is almost empty, because drug companies have shifted their research from short-term-use antibiotics to more lucrative drugs for treating chronic conditions such as heart disease, cancer and AIDS.

Unless we change our practices, even the occasional new antibiotic will become obsolete. For instance, the new antibiotic Synercid is one of the last hopes against deadly antibiotic-resistant bloodstream infections. Although it has not yet been approved for use in humans, its value has been compromised because resistance to one antibiotic can cause resistance to others: Researchers at Wayne State University have found Synercid-resistant bacteria in turkeys that had been fed another antibiotic. If that resistance jumps to bacteria that infect humans, Synercid will be much less useful.

The incidence of vancomycin-resistant staphylococcus should move the government, the medical community, drug companies, agribusiness and consumers to join forces to solve this complex problem before it is too late. Reforms should include:

* barring medical and insurance practices that lead to unnecessary prescriptions;

* informing patients that antibiotics are inappropriate for all colds and many sore throats, ear, sinus and bronchial infections;

* halting all uses of antibiotics in agriculture that jeopardize the drugs’ effectiveness in humans;

* adopting national targets for reductions in antibiotic usage.

Without such changes, the crown jewels of modern medicine may turn to dust.